'The Family Upstairs' is the 'GMA' Book Club pick for November

Critics are calling the book "haunting" and "completely consuming."

For round two of "GMA's" first book club, we're reading the new psychological thriller novel, "The Family Upstairs," by Lisa Jewell.

We announced the book as this month's pick on our "GMA Cover to Cover" Instagram last week when "The Family Upstairs" hit shelves.

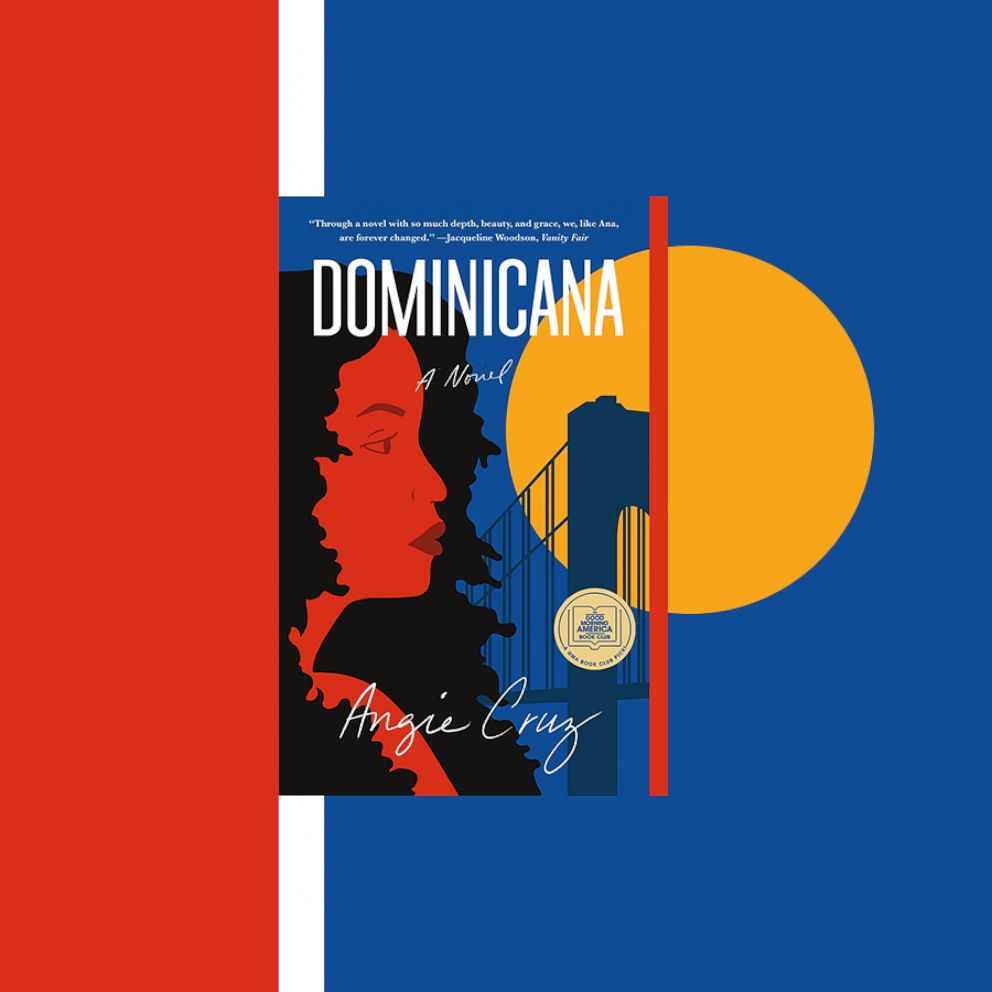

GMA Cover to Cover took off with a great start last month as we read Angie Cruz's "Dominicana," a story of strength and sacrifice inspired by Cruz's own mother who immigrated to New York City.

Now, we're switching gears to a page-turning whodunit, dripping with twists and suspense. Critics have called the novel "enthralling" and a "stay-up-way-too-late read."

This is London-based author Lisa Jewell's 17th novel. The story follows 25-year-old Libby Jones as she discovers some chilling family secrets -- all in the shadow of a mystery that resulted in three dead bodies and two missing children.

Jewell gave "GMA" an exclusive look into her unexpected inspiration for the novel.

"'The Family Upstairs' was actually inspired two years ago by a woman I saw in the south of France who was smuggling her two children into the private shower block of a beach club. She looked kind of furtive and a bit frantic. She looked like she had some sort of secret that she was hiding or something that she was escaping from, and I couldn't stop thinking about this woman," Jewell told "GMA."

More about 'The Family Upstairs' by Lisa Jewell

Be careful who you let in.

Soon after her twenty-fifth birthday, Libby Jones returns home from work to find the letter she's been waiting for her entire life. She rips it open with one driving thought: I am finally going to know who I am.

She soon learns not only the identity of her birth parents, but also that she is the sole inheritor of their abandoned mansion on the banks of the Thames in London's fashionable Chelsea neighborhood, worth millions. Everything in Libby's life is about to change. But what she can't possibly know is that others have been waiting for this day as well—and she is on a collision course to meet them.

Twenty-five years ago, police were called to 16 Cheyne Walk with reports of a baby crying. When they arrived, they found a healthy ten-month-old happily cooing in her crib in the bedroom. Downstairs in the kitchen lay three dead bodies, all dressed in black, next to a hastily scrawled note. And the four other children reported to live at Cheyne Walk were gone.

In "The Family Upstairs," the master of "bone-chilling suspense" (People) brings us the can't-look-away story of three entangled families living in a house with the darkest of secrets.

Start reading now with an excerpt:

Libby picks up the letter off the doormat. She turns it in her hands. It looks very formal; the envelope is cream in color, made of high-grade paper, and feels as though it might even be lined with tissue. The postal frank says: "Smithkin Rudd & Royle Solicitors, Chelsea Manor Street, SW3."

She takes the letter into the kitchen and sits it on the table while she fills the kettle and puts a tea bag in a mug. Libby is pretty sure she knows what's in the envelope. She turned twenty-five last month. She's been subconsciously waiting for this envelope. But now that it's here she's not sure she can face opening it.

She picks up her phone and calls her mother.

"Mum," she says. "It's here. The letter from the trustees."

She hears a silence at the other end of the line. She pictures her mum in her own kitchen, a thousand miles away in Dénia: pristine white units, lime-green color-coordinated kitchen ac- cessories, sliding glass doors onto a small terrace with a distant view to the Mediterranean, her phone held to her ear in the crystal-studded case that she refers to as her bling.

"Oh," she says. "Right. Gosh. Have you opened it?" "No. Not yet. I'm just having a cup of tea first."

"Right," she says again. Then she says, "Shall I stay on the line? While you do it?"

"Yes," says Libby. "Please."

She feels a little breathless, as she sometimes does when she's just about to stand up and give a sales presentation at work, like she's had a strong coffee. She takes the tea bag out of the mug and sits down. Her fingers caress the corner of the envelope and she inhales.

"OK," she says to her mother, "I'm doing it. I'm doing it right now."

Her mum knows what's in here. Or at least she has an idea, though she was never told formally what was in the trust. It might, as she has always said, be a teapot and a ten-pound note.

Libby clears her throat and slides her finger under the flap. She pulls out a sheet of thick cream paper and scans it quickly:

To Miss Libby Louise Jones

As trustee of the Henry and Martina Lamb Trust created on 12 July 1977, I propose to make the distribution from it to you described in the attached schedule . . .

She puts down the covering letter and pulls out the accom- panying paperwork.

"Well?" says her mum, breathlessly. "Still reading," she replies.

She skims and her eye is caught by the name of a property. Sixteen Cheyne Walk, SW3. She assumes it is the property her birth parents were living in when they died. She knows it was in Chelsea. She knows it was big. She assumed it was long gone. Boarded up. Sold. Her breath catches hard at the back of her throat when she realizes what she's just read.

"Er," she says.

"What?"

"It looks like . . . No, that can't be right."

"What!"

"The house. They've left me the house." "The Chelsea house?"

"Yes," she says. "The whole house?"

"I think so." There's a covering letter, something about no- body else named on the trust coming forward in due time. She can't digest it at all.

"My God. I mean, that must be worth . . ."

Libby breathes in sharply and raises her gaze to the ceiling. "This must be wrong," she says. "This must be a mistake."

"Go and see the solicitors," says her mother. "Call them. Make an appointment. Make sure it's not a mistake."

"But what if it's not a mistake? What if it's true?"

"Well then, my angel," says her mother—and Libby can hear her smile from all these miles away—"you'll be a very rich woman indeed."

Libby ends the call and stares around her kitchen. Five minutes ago, this kitchen was the only kitchen she could afford, this flat the only one she could buy, here in this quiet street of terraced cottages in the backwaters of St. Albans. She remembers the flats and houses she saw during her online searches, the little in- takes of breath as her eye caught upon the perfect place—a sun- trap terrace, an eat-in kitchen, a five-minute walk to the station, a bulge of ancient leaded windows, the suggestion of cathedral bells from across a green—and then she would see the price and feel herself a fool for ever thinking it might be for her.

She compromised on everything in the end to find a place that was close to her job and not too far from the train station. There was no gut instinct as she stepped across the threshold; her heart said nothing to her as the estate agent showed her around. But she made it a home to be proud of, painstakingly creaming off the best that T.J.Maxx had to offer, and now her badly converted, slightly awkward one-bedroom flat makes her feel happy. She bought it; she adorned it. It belongs to her.

But now it appears she is the owner of a house on the finest street in Chelsea and suddenly her flat looks like a ridiculous joke. Everything that was important to her five minutes ago feels like a joke—the £1,500-a-year raise she was just awarded at work, the hen weekend in Barcelona next month that took her six months to save for, the MAC eye shadow she "allowed" herself to buy last weekend as a treat for getting the pay raise, the soft frisson of abandoning her tightly managed monthly budget for just one glossy, sweet-smelling moment in House of Fraser, the weightlessness of the tiny MAC bag swinging from her hand, the shiver of placing the little black capsule in her makeup bag, of knowing that she owned it, that she might in fact wear it in Barcelona, where she might also wear the dress her mother bought her for Christmas, the one from French Connection with the lace panels she'd wanted for ages. Five minutes ago her joys in life were small, anticipated, longed-for, hard-earned and saved-up-for, inconsequential little splurges that meant nothing in the scheme of things but gave the flat surface of her life enough sparkles to make it worth getting out of bed every morning to go and do a job which she liked but didn't love.

Now she owns a house in Chelsea and the proportions of her existence have been blown apart.

She slides the letter back into its expensive envelope and finishes her tea.