Doctor pays tribute to his parents with graduation photos in the fields where they work

"It wasn't really a planned out idea. It just happened."

A recent doctoral graduate is honoring his parents by taking photos in the fields of the farm where they work after every degree he gets.

Dr. Erick Martínez Juárez, 29, graduated from the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University earlier this spring and is now a neurology resident at UCLA Health. After Juárez received his M.D., he went back to the tomato fields in Decatur County, Georgia, where his parents work to take photos in full regalia.

"It wasn't really a planned out idea," Juárez told "Good Morning America" of how it all started. "It just happened."

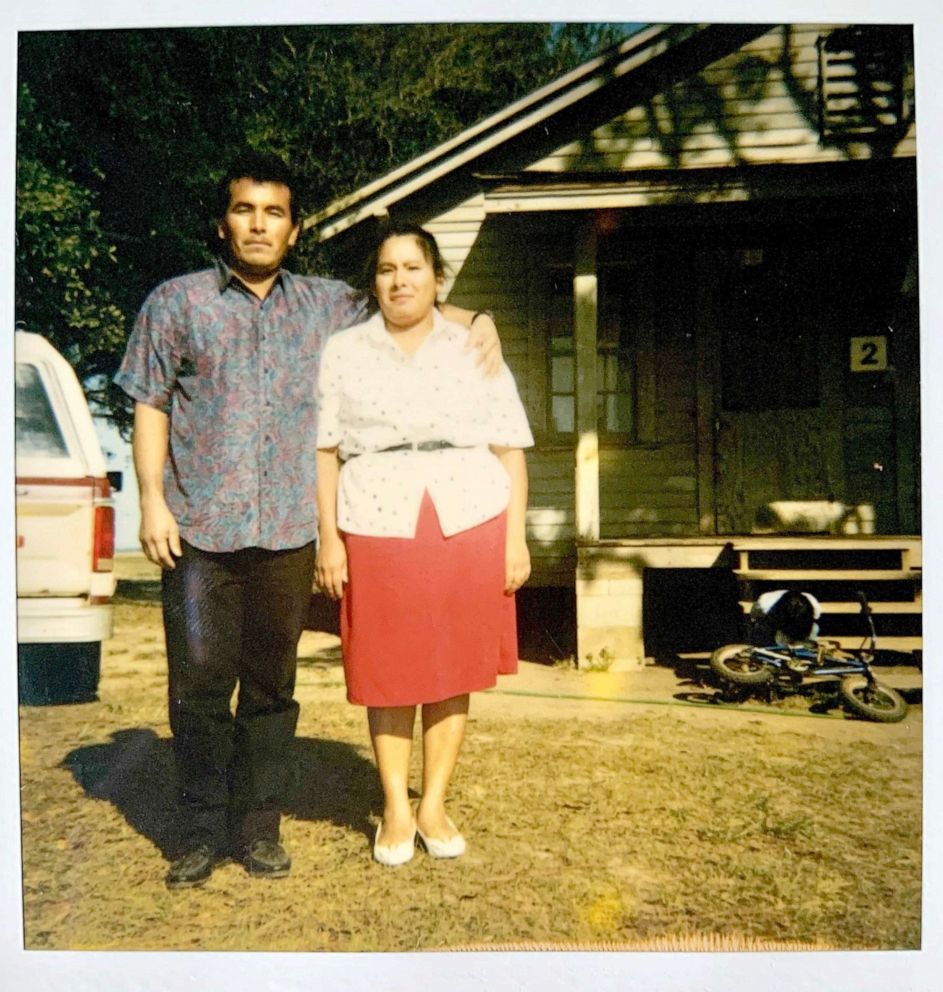

The first iteration of the idea came after Juárez's graduation from Harvard University in 2015, where he received a bachelor of arts in neurobiology. He went back to the fields and, while not in his graduation gown, took a photo with his father to commemorate the occasion.

"That's the first photo that I inadvertently set up," he said. "But it has become a tradition now that I've graduated from medical school. I plan to do the same in three or four years when I complete my neurology residency."

In May 2020, he and his four other siblings -- Raul, 30; Carmen, 23; Jesus, 21; and Maria Guadalupe, 19 -- all took photos in their high school graduation gowns in the fields.

Juárez attributes his success to the hard work, dedication and sacrifices of his parents, Loreto, 56, and Maricela, 52, and said the photos came about as a way to honor that.

"They're my biggest sources of motivation," he said. "I feel like the best method of honoring my parents at this moment in my career, at this moment in my life, would be to share their story."

Humble beginnings

According to Juárez, his parents come from modest means. Raised on a ranch, they were each the oldest of 10 siblings, had little money, and were forced to drop out of school early on in their education to help make ends meet.

They immigrated to the United States from Mexico in the 1980s in search of a better life, his parents told "GMA." Their journey was a difficult one, where they faced many challenges along the way.

"There was one point where my mother was crossing the Rio Grande, and despite its shallowness in that part of the river, she almost drowned and almost never made it," Juárez said.

Only in their 20s at the time, Juárez's parents arrived in time to be two of the nearly three million beneficiaries of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act. The act provided amnesty to immigrants and allowed them to apply for legal status.

"They had immigrated here just in time," Juárez said. "So ever since they got here, they've been blessed by having papers, as the locals would say."

While the amnesty assuaged one of their worries, life in the U.S. was no easy feat.

"The journey once stateside was as difficult if not more," he said. "Without the money, without the social, cultural capital, they really had to navigate things on their own."

Eventually, Juárez's parents got in touch with people who connected them with farmworker jobs. They cultivated produce in North Carolina and picked oranges in Florida before making their way to a migrant farmworker camp in Attapulgus, Georgia, in the 1990s.

Learning the details of his parents' stories was "icing on the cake of pride and joy" that Juárez has for his parents.

"I've always been proud of my parents," he said. "When people eventually ask me, 'Hey, what do your parents do for a living?' with the utmost pride, I tell them, 'Yeah, they're farmworkers.'"

His parents feel the same pride and admiration toward him. With all his accomplishment thus far, he hasn't forgotten where he came from.

"We're proud of our son," Maricela Juárez said. "He's not ashamed of us."

Seeing what his parents did to provide their family with better opportunities, Juárez was compelled to mirror their work ethic.

In 2010, Juárez graduated from Bainbridge High School as the first Hispanic valedictorian in the school's history.

His graduation from Harvard made him the first in his family to graduate from college.

A desire to give back

Juárez's inspiration to become a doctor stemmed from his time living in the migrant camp. Every summer while growing up, he would watch physicians from the Emory Farmworker Project (EFP) provide health care services to the camp's farmworkers.

"That was the first time I was exposed to a profession outside of education or agriculture," Juárez said. "I was just fascinated by the fact that you can make a living by helping heal people."

Through Medicaid, Juárez said he was able to see his pediatrician as needed, but the EFP was the first time that he saw health care in action helping underserved communities and he wanted to do the same.

Juárez said despite his parents' limited scope of knowledge on higher education, they were very supportive and encouraging.

"They granted me an extra degree of autonomy as far as big life decisions," he said. "They would always tell me, 'Erick, you do whatever you want to do. We'll encourage you and have your back. With what little financial support we have, we'll support you. But this is pretty much your life and we want you to do what's best for you.'"

In addition to giving back through medicine, Juárez is also considering a career in public service or politics.