How this Hallmark Channel star is working to help fix the foster care system in US

Jen Lilley and her husband, Jason Wayne, are longtime foster parents.

Jen Lilley, a soap opera star and regular in Hallmark Channel movies, says being a foster parent has changed her life "in so many ways."

The 36-year-old mom of three is now on a mission to help change the foster care system in the United States so that kids can more successfully reunite with their birth families.

"A lot of lives in foster care would be saved if it came down to common sense, but it doesn't always come down to common sense," Lilley told "Good Morning America," noting that red flags are often ignored in order to reunify families. "You end up having reentry into foster care, unsuccessful reunification and a lot of times death because sometimes they're just looking at the law and they're not really looking at what's in the best interest of the child."

Lilley herself has experienced the ups and downs of the foster care system since 2016, when she and her husband, Jason Wayne, became foster parents to their now 4-year-old son Kayden, when he was just 4 months old.

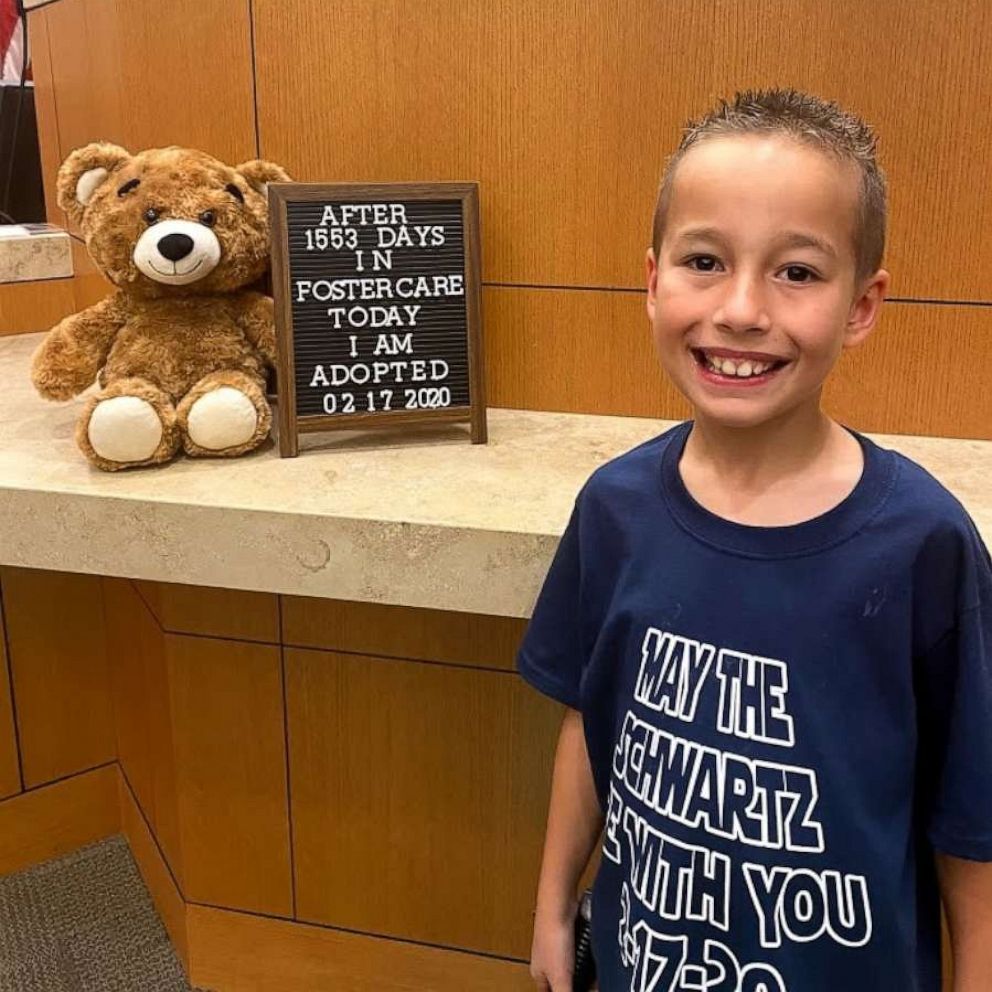

The couple adopted Kayden last year after several years of trying to reunite him with his birth mother.

"She came from foster care," Lilley said of the mom, who also birthed a second son Lilley and Wayne are in the process of adopting. "That's what you'll find with foster care. It's a cycle and it's a really hard cycle to break."

In California, where Lilley and her family live, the process to reunite a child with a birth relative starts with monitored visits, then goes to short, unmonitored visits and then includes a home pass, where a child can stay overnight for a night or two at their birth parents' or relatives' home, according to Lilley.

It is a protocol that she wants to see extended nationwide. In other states, the process stops at the unmonitored visits and does not include a chance for the child to stay overnight, which gives the caregiver a chance to make sure they are equipped to welcome the child back home, according to Lilley, whose podcast, "Fostering Hope with Jen Lilley," delves into the issues surrounding foster care.

"It's a chance for parents to dip their toe into the pool of parenting again, give them a light at the end of the tunnel, keep their therapy and services continuing," she said. "And when you tell a child, 'You're just going to go for one night and then you're going to go back to your foster home,' that gives them a chance to mitigate their anxiety."

Lilley traveled to Washington, D.C., in July to lobby lawmakers to adopt the California reunification model in their own states, though the decision will ultimately be made at more local levels.

"That's why foster care is so complicated, every state has a different policy and within the state every county has a different policy and within the county every agency has a different policy," said Lilley. "[We also need] states to communicate with each other."

There were more than 420,000 children in the foster care system as of last year, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Federal law requires individual states to establish a permanency plan for every child in foster care, which is used to not only determine where the child will live but also ensure that those fighting for custody of a child are prepared to take it on and can meet the child's needs. If a child remains in foster care for 15 out of 22 months, federal law requires the child welfare agency to ask the court to terminate parental rights, according to the Federal Children's Bureau, a division of HHS.

The nationwide shutdown during the coronavirus pandemic has put family reunification hearings across the country on hold as courts are either closed or operating on a limited basis, threatening to create a backlog of custody cases that could delay family reunifications for thousands of children.

Throughout the foster care system, around 3 in 5 children return home to their parents or other family members after being placed in foster care, according to HHS.

Lilley, also mom to a 1-year-old daughter, may be best known as an actress and singer, but she describes advocating for children in the foster care system as her life's work. Her goal is to make sure kids are well cared for in safe and happy homes, ideally by their birth parents or relatives.

"The goal of foster care is absolutely not adoption," she said. "Adoption is supposed to be only when necessary, so people who get into foster care to adopt are in it for the wrong reason."

Lilley added she understands not everyone can be a foster parent, but said there are things everyone can do to help, whether by volunteering services, donating items to foster families or signing up to be a court-appointed advocate or becoming a licensed babysitter to give foster parents a break.

"Everybody can do something," she said. "I believe as a society, that these are our children, these are America's children, and we have responsibility as a community to care for them."

ABC News' Tonya Simpson contributed to this report.