Why parents should be concerned about cameras in classrooms: Advocates

It's not as simple as it sounds, an expert warns.

As the nation's children head back to school -- some in-person, some remote and some in a "hybrid" model combining both -- there's very likely a new piece of technology in your child's classroom that some say should give parents a major pause: a camera.

Schools offering a choice between in-person learning and remote learning are likely placing a camera in the classroom and allowing students and their parents, to watch what's happening in the classroom via a livestream.

But privacy advocates say what sounds like a simple solution to a gigantic problem -- teaching kids at home and at school at the same time -- is anything but.

"Good Morning America" spoke with Consumer Reports privacy director Bill Fitzgerald, also a former classroom teacher, about the myriad problems he feels cameras in classrooms may pose.

"Nobody is as concerned as they should be," he told "GMA."

Privacy

The most obvious issue with cameras in classrooms is privacy, for both students and teachers.

"When a classroom is running well," Fitzgerald told "GMA," "kids are allowed to be vulnerable and make mistakes. It's at least a semi-private place. When a camera is in the class, that level of comfort is destroyed."

Fitzgerald said while schools are generally very protective about who can see what's captured on closed-circuit cameras that are primarily used for security, once a camera is placed into a classroom and broadcast into people's homes, there's no control over who sees the content.

"Anyone can capture a screenshot or take a video [of the feed]," he said. "It only takes one cruel student or one cruel parent to take a video to mock your kid."

Developmental risks

Teachers will not teach the same way they would if there wasn't a camera in the classroom, Fitzgerald said.

"Teachers will be keenly aware of [the camera] while students will not. There are developmental risks in both," he said.

It's likely, he said, that some teachers will be harassed by overzealous parents -- some may think the teacher is too liberal or too conservative in their teaching methods. "It raises the stakes over what occurs in a classroom," he said, noting that something that makes perfect sense in the context of the classroom might not when taken out of context -- a risk when people can record a camera feed.

Equity

Earlier this week, a school district in Tennessee made headlines for asking parents to sign a waiver stating that they would not watch their children's online classes, citing student privacy. They have since clarified the request after pushback, by issuing new guidance suggesting parents not share or record information on other students, according to local news reports.

But, Fitzgerald said, this request is laden with privilege.

"It assumes that every student has access to a screen that's not able to be seen by others in their household," he told "GMA." Plus, he said, "parents should not be forced to give up basic rights for the convenience of the people running the schools."

The pandemic, he said, did not cause equity issues, it instead "exposes the inequities we have been comfortable ignoring for decades."

Possible solutions

While Fitzgerald said he would not send his own children into a classroom where they would be on camera hours each day, he suggested a few ways to better control the camera-in-classroom issues.

First, he said, it's time to think about school buildings not as places to be filled, but instead, as tools to be accessed by students most in need.

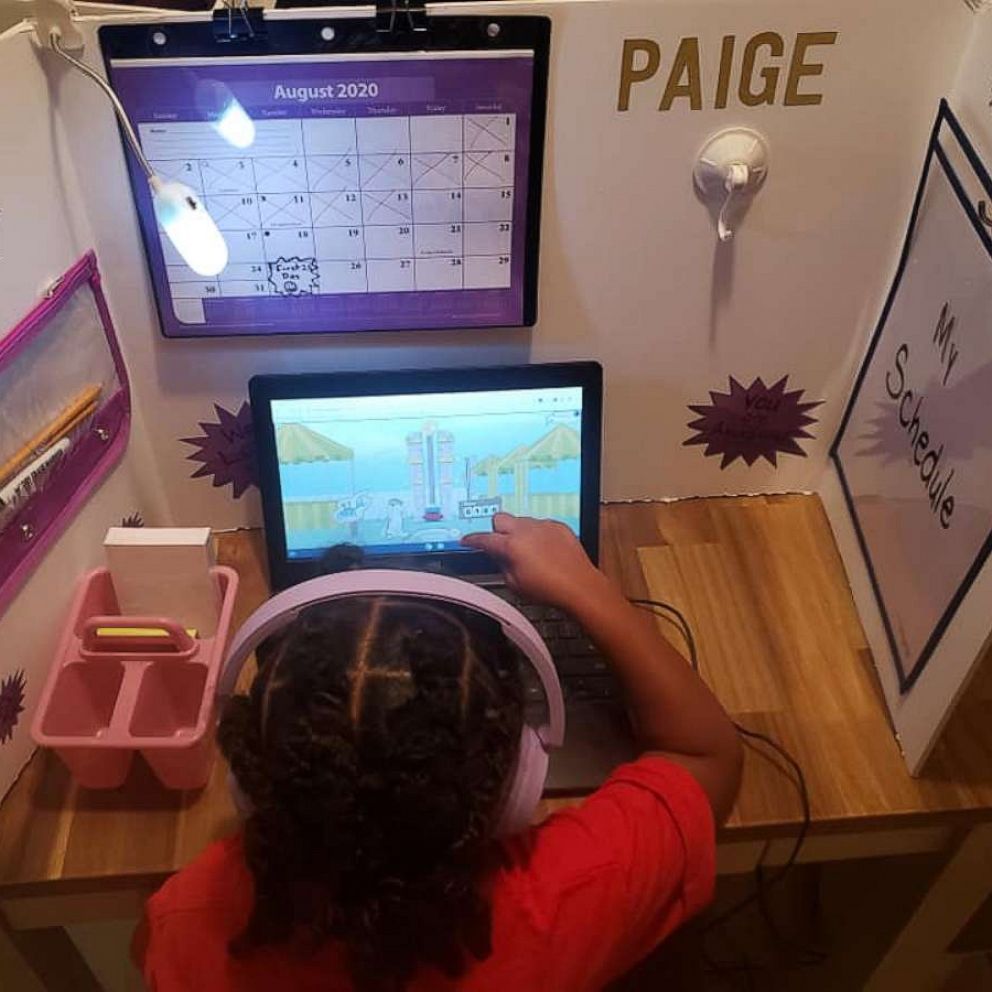

Access, Fitzgerald told "GMA" should be "staggered by age and by need.” Younger students and those with learning differences who need in-person interaction should have priority, he said, as well as children of essential workers and those for whom English is not their native language.

But for those schools where cameras are or about to be up and running, he offered a few suggestions.

"The technology should be used to deliver the content," he said, suggesting short 5- to 10-minute lessons focused on key takeaways that can be utilized by both in-person and at-home learners. "Lessons should optimized for remote learning and then adapted for face-to-face instruction with supplemental materials."

Once the content is delivered to the students, teachers can then foster emotional relationships with the students in the classroom, he said.

Meanwhile, parents and teachers can advocate for a second adult in the classroom to either facilitate technology and support remote learners or support the in-person learners, Fitzgerald said, adding that "it's not reasonable to expect teachers to do double duty."