At the center of the immigration debate, 1st-generation college students are revolutionizing campuses

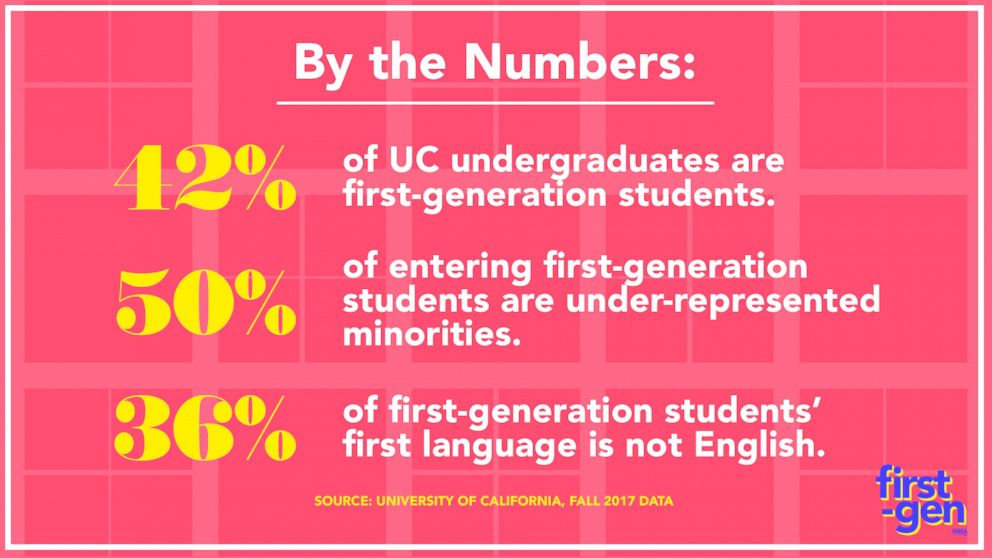

First-gen students make up 42% of undergrads in the University of Cal system.

The state of California is the face of a changing America, with an increasingly diverse population and a stake right in the center of the immigration debate.

In the middle of that changing landscape are the state's college campuses. In the University of California system, a network of 10 campuses serving some 270,000 students, first-generation college students make up nearly half of all undergraduates.

The system's undergraduate admissions policy is designed to give opportunities to underrepresented groups, including first-generation students, and dorms, resource centers and summer programs specifically for first-generation students are common on campuses.

The University of California defines a first-generation student as a student from a family where neither parent has graduated with a four-year college degree.

Of the 42 percent of UC-system undergraduates who are first-generation students, about 12 percent are white, according to UC data.

Half of first-generation students entering in fall 2017 were under-represented minorities, and 36 percent of first-generation students have a first language other than English. UC's first-generation students are also more likely to enter as transfer students and/or have a lower income than students with at least one parent who graduated from college, according to UC.

Some University of California officials themselves were surprised to see that a such a large first-generation, minority student body population emerge.

"It blew our minds," said Anita Casavantes Bradford, a professor of Chicano/Latino studies at University of California Irvine. "The fact that this is a top research university that people really want to go to that is also serving first-generation, low-income, Latino and immigrant students in massive numbers, that realization is a big deal."

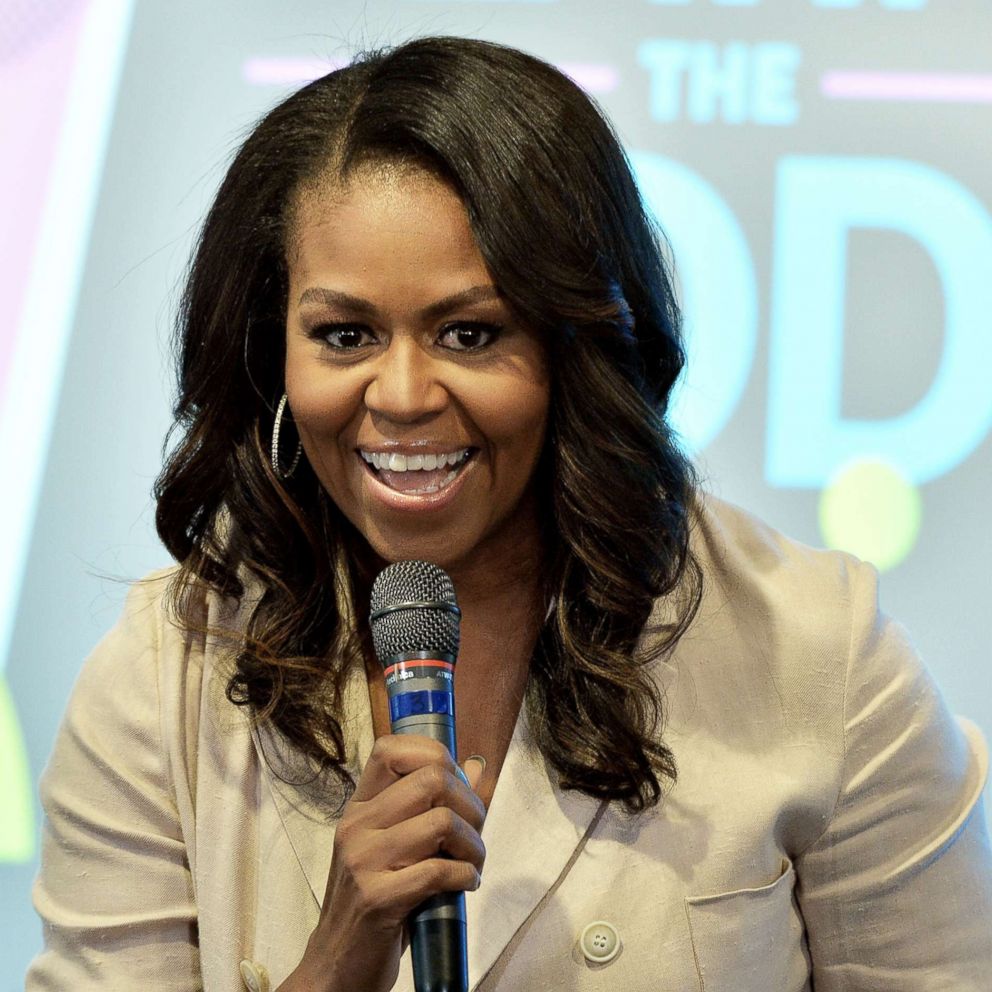

"GMA" is spotlighting the stories of first-generation college students. Explore our full coverage.

A first-of-its-kind program for first-gen students

Casavantes Bradford, a first-generation college graduate, daughter of a Latino father who immigrated to Canada and herself an immigrant to the U.S., has played a major role in how first-generation students have found success at UC universities.

In 2014, she was part of a newly formed team of first-gen faculty and staff advocates to discover that UC Irvine, a prestigious public research university in Orange County, is a majority first-generation campus. And not only were its students largely first-generation, many of the school's faculty members also were.

"When you're first-generation here, you're not alone and you're not a minority," Casavantes Bradford said. "You are the new normal, and not just are you the new normal, we're excited about that. We're proud of it."

Inspired by first-generation students she met who were not applying to graduate school because they had bad grades their freshman year, Casavantes Bradford began her work to reach first-generation students as soon as they stepped on campus.

She started offering workshops for faculty members to help them understand first-generation students' unique experiences and needs. She then began a faculty-student mentor program that pairs a first-generation faculty member with a first-generation undergraduate.

Last year, UC implemented Casavantes Bradford's faculty-student mentor program across all 10 of its campuses with the help of about 900 first-generation faculty.

In addition to the mentor program, faculty members wear T-shirts and lapel pins on campus identifying themselves as first-generation graduates.

"Instead of saying first [generation] is defined by academic deficiency or defined by a lack of cultural capital, we say first-gen means that you're brave," said Casavantes Bradford said. "It means you're willing to confront the unknown."

"It means you have such a strong sense of self that you're willing to step out of everything you know and go for something that calls to you," she said. "A first-gen kid, if they understand all of those strengths, and if we help them to harness those strengths, they're unstoppable."

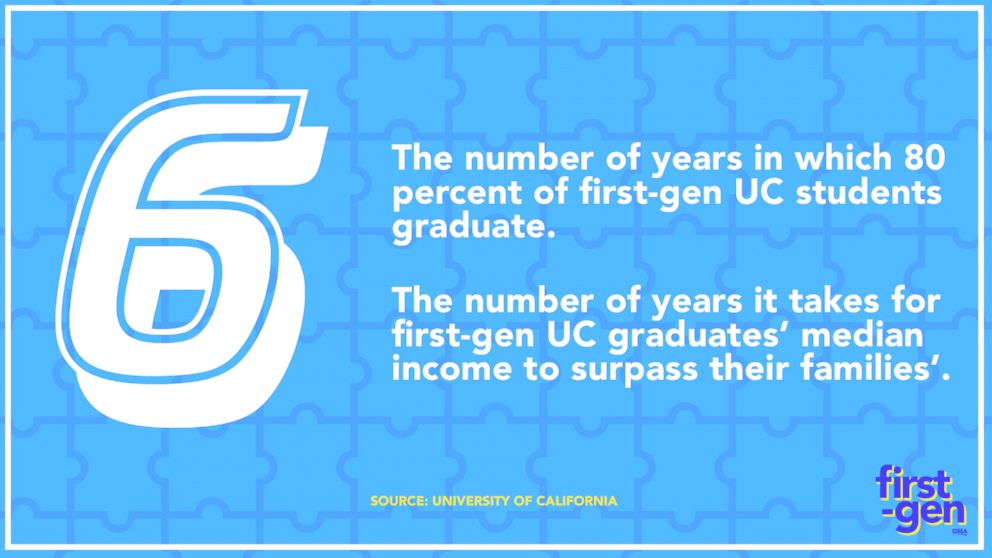

Today, across the UC system, 80 percent of first-generation students graduate in six years. And they graduate not only with a degree but with economic mobility too. Six years after graduation, UC first-generation students' median income largely has surpassed that of their families', according to UC data.

A first-gen student's experience

Ana Laura Govea Grajeda, a rising senior at UC Irvine, is a first-generation student who moved to the U.S. from Mexico when she was 4.

Like many first-generation students, Grajeda, 21, was motivated to attend college to create a better life not just for herself but also for her parents and three siblings. Her parents have only middle and high school educations and have worked labor-intensive jobs since moving to San Bernardino, California, where Grajeda was raised.

"As I got older, I started to realize that other people lived better than me, that their parents had education or longer time in the U.S.," she said. "Once I got to middle school and high school, I knew that I had to, and I wanted to, go to college, because I wanted a better future for myself and my family."

Grajeda figured out her college applications and financial aid on her own, without help from her parents or high school advisers, where attending college was not expected of most students. She was introduced to UC Irvine by her older sister, a University of California Los Angeles graduate, who took her to a college campus for the first time.

When Grajeda began her studies as a math major, she encountered obstacles that are exactly why Casavantes Bradford has said she created the faculty-student mentor program.

Grajeda recalled that in her freshman year, when she went to the math advising center with a question about a class, she was told that she should switch out of math as a major.

"Going into math classes, there was no one who looked like me, so it was so hard for me to believe that I belonged there, that I was good enough to be there and good enough to compete with these people," she recalled. "After that experience, I stopped going to the math advising center, and I just put it on myself to do well."

She added, "As the years have gone by, I've been my own motivation. I have to do this. I'm going to do this and no one is going to stop me."

In her sophomore year, Grajeda found a mentor through the faculty-student mentor program and began working for Student Success Initiatives, an on-campus resource center for students ranging from first-generation to low-income, undocumented, transfer students.

"I tell [new first-generation students] to go into [SSI] because it's the first space that I felt comfortable in," she said. "I tell them to not give up because there were so many instances where I wanted to just drop out of not only my major, but maybe even college."

"It takes more than one person to get a student to graduate," Grajeda added. "I believe that with all my heart."

First-generation student and facing a deportation threat

Despite her obstacles as a first-generation student, Grajeda considers herself lucky because she attends college as a U.S. citizen.

Many first-generation students in the UC system, such as Daysy Gabriela Palma, face the additional burden of trying to finish college as they live under the very real threat of deportation.

Palma, who graduated this year from UCLA, benefited from the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy that allows undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. illegally as children to remain in the country.

Last September, President Donald Trump announced that his administration would repeal the program and set a deadline for Congress to create a legislative fix for Dreamers. Congress has yet to take up any significant legislation to resolve the DACA issue, and Trump's attempts to end the program have been delayed by multiple legal challenges.

Those legal challenges allowed Palma time to renew her DACA employment authorization for another two years. It was set to expire this month.

"After the 2016 election, I was really worried that I wouldn't be able to work and benefit from my degree," she said. "I knew I wanted to honor my parents' sacrifices in the best way possible and getting this college degree was only a small testament to all of their sacrifices and efforts to allowing me to live such a beautiful life [in the U.S.]."

Palma chose UCLA because she wanted to be close to her parents, who remain undocumented, to help them if they ran into immigration trouble. She came to California from Mexico with them when she was 3.

"I didn't know I was undocumented until I was a senior in high school applying for financial aid," Palma said. "That's when I knew I didn't have a Social Security card."

"After that, I had to fill out applications on my own," she recalled. "Because I was the only one undocumented in my class going to a four-year university, my high school counselors couldn't help me."

At UCLA, which has a large population of undocumented students, Palma utilized the services of lawyers who are available on-campus to help undocumented students with legal issues including DACA renewals. She also sought the help of mental health services made available to students dealing with the challenges of being both a first-generation and an undocumented college student.

"Being a first-gen and undocumented, there was a first for everything, and everything I had to learn by extending myself and going out of my way," she said. "It was very challenging and it was very intimidating, most of all because I doubted my own potential."

Palma was not eligible for federal financial aid because she's undocumented. She worked hard to find scholarships to cover her tuition in addition to two on-campus jobs to cover her living expenses.

"Not a lot of students qualify for DACA, and without DACA they can't get a work permit, so I consider myself very, very lucky," she said.

Palma also volunteered on campus as a peer counselor, was active in student government and helped lead a student-run immigration advocacy group. She was also instrumental in creating UCLA's first-ever retention program for undocumented students to help keep them in school and on track for graduation.

Palma plans to attend law school to become an immigration attorney so she can work to make the system "more inclusive and tolerance-based." Guiding her on her path to law school is her UCLA faculty mentor, who is also an immigrant and a first-generation college student.

"She definitely gave me my wings to fly," Palma said.

First-gen students changing admissions, campus life

Across the UC system, the number of first-generation students has grown 6 percent in 10 years.

In contrast, the percentage of first-generation college students, defined as students whose parents did not attend college, across the U.S. has decreased, from 37 percent in 2000 to 33 percent in 2012, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

To get more first-generation students on its campuses, UC starts reaching out before the students even apply for college. Its Student Academic Preparation and Educational Partnerships program offers academic support in under-resourced schools across the state to help prepare students for higher education.

When students do apply to the system's undergraduate campuses, they do so under a comprehensive-review admissions policy designed to give opportunities to underrepresented groups, like first-generation students. The policy looks "beyond GPA and standardized test scores to evaluate students' academic achievements in light of the opportunities that were available to them and any challenges they may have faced," a UC spokesperson told "GMA."

California seniors who are in the top 9 percent of their graduating high school class and meet the requirements for freshmen admission are also guaranteed a spot at a UC school.

On campus, in addition to the faculty-mentor program, each UC undergraduate campus has a program specifically dedicated to offering first-generation students academic support, financial advising and social and networking opportunities. Some on-campus housing is now set aside just for first-gen students. Summer programs have been added to help those students' transition to college.

UC Irvine's First Generation, First Quarter Challenge, also created by Casavantes Bradford, is one of the many events UC campuses have started offering to help reach first-generation students early on.

"If you're doing it right, then you're going to have a level of excitement and innovation and energy in an academic environment -- if you bring under-represented students into that space and harness the things that they bring that other students don't," said Casavantes Bradford. "You're going to get an energy that you don't get anywhere else."