Personal essay: What I've learned after living with HIV in secret for years

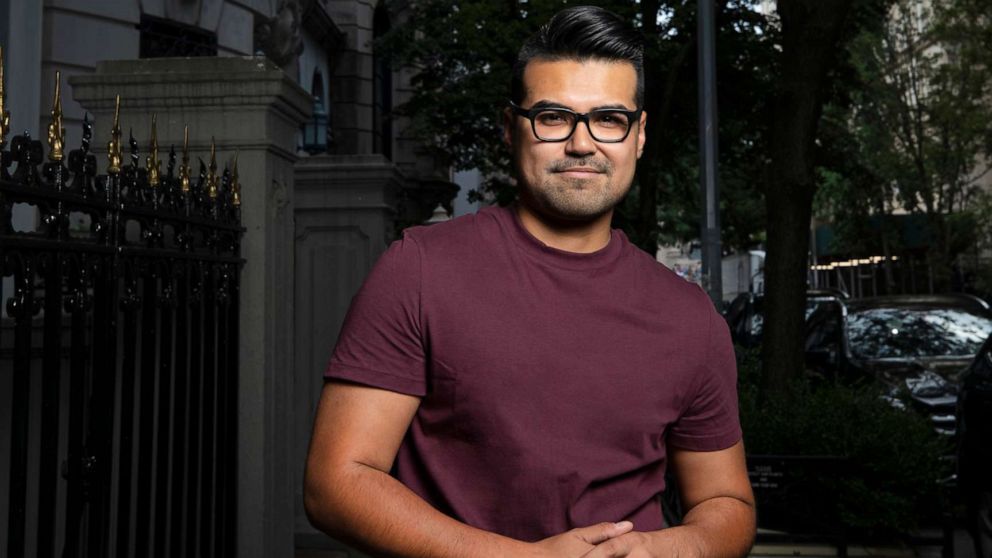

ABC News' Tony Morrison opens up on the 8th anniversary of his HIV diagnosis.

On the eighth anniversary of his HIV diagnosis, ABC News producer Tony Morrison, 32, opens up for the first time about his experience living with HIV in a personal essay.

I have been living with HIV for eight years.

It has taken me eight years and a global pandemic to be able to articulate those words confidently and put to paper.

Not a day has gone by that I didn’t feel shame, fear, guilt and often, anguish. And I have lived every single one of those days carrying a weight of humiliation, because that’s what society told me I should feel; that’s what our society told me I deserved. And I know that’s what society has probably whispered to you too, about people like me.

I allowed myself to think my shame was justified.

I accepted a life as a degenerate.

And I convinced myself I could never be worthy of love.

For eight years, I dealt with my diagnosis in hiding and I grieved in silence.

Until now.

I wish I could say that I chose this time to speak out, except, I feel that it’s this time we are in that chose me. During the pandemic, with nowhere else to look but the mirror, I found the courage to face myself and the fortitude to live honestly and openly.

Now, as I look ahead to what my post-COVID life could be, I refuse to return to the world as that same person I left it, hiding in the shadows of my shame.

For me, it was a devastating diagnosis, just months after moving to New York City from the small town of Winter Garden in Central Florida. I was 23 and wanted to start a new life in the Big Apple, as so many do.

It was the spring of 2013 and I had just officially come out as gay in a heartfelt Facebook post. I was free from hiding, so I thought, and was determined to finally live the life I had always wanted.

I felt like I could finally be me.

At the time, I noticed a campaign across New York City for HIV testing. Friends would go and get tested together in a mobile testing location outside of neighborhood bars and clubs in Hell’s Kitchen and the West Village.

I suppose it was "fashionable" to get tested and receive a negative test result but I certainly didn’t know of anyone living with HIV at the time. And there was no education, at least in my spheres, explaining what to do if you were to receive a positive result.

I was afraid to be seen doing any of this in public, for fear of what could be said about me if I was spotted taking an HIV test. So, out of curiosity, I got a simple over-the-counter, at-home self test. A few swabs to the gums and I'd have my results in 20 minutes, the packaging detailed.

It was as awful as you think it would be.

I stared at the test result endlessly and I felt completely numb and devoid of emotion.

Before I could process anything, my thoughts spiraled and I immediately internalized it all. I told myself I couldn't cry.

Would my life ever be the same?

Are my days on the planet numbered?

How could I tell my mom the nightmare of having a gay son was realized in this way?

The test result of HIV-positive sent me running back into the closet I had proudly come out of just weeks before.

And most notably, I remember feeling alone.

I hid my panic in public, whether at work or out with friends and I kept the news to myself for three days, not knowing who or how to tell anyone.

Those three days were excruciating and tiring.

By the end of that week, I broke down and finally shared the news separately with three of my closest friends. And while they all responded with love, there was an element of mystery and of course, fear — none of us knew how to deal with this. I remember vividly how one of those friends told me, “I really wish I knew how to help.”

“Me too,” I replied.

Wondering how long I had to live, I scheduled what felt like a barrage of appointments with doctors and specialists, more than I could count, to try and confirm my fate. Each visit and conversation became more definitive than the one before about my diagnosis.

There was no turning back.

This was going to be my new life.

But I didn't want anyone to know. What would they all think of me?

I didn't want anyone to know. What would they all think of me?

I finally landed in the care of a doctor who I will never forget. She was kind and patient and was the first to assure me that my life had only just begun.

Most of all, she told me that I wasn’t alone.

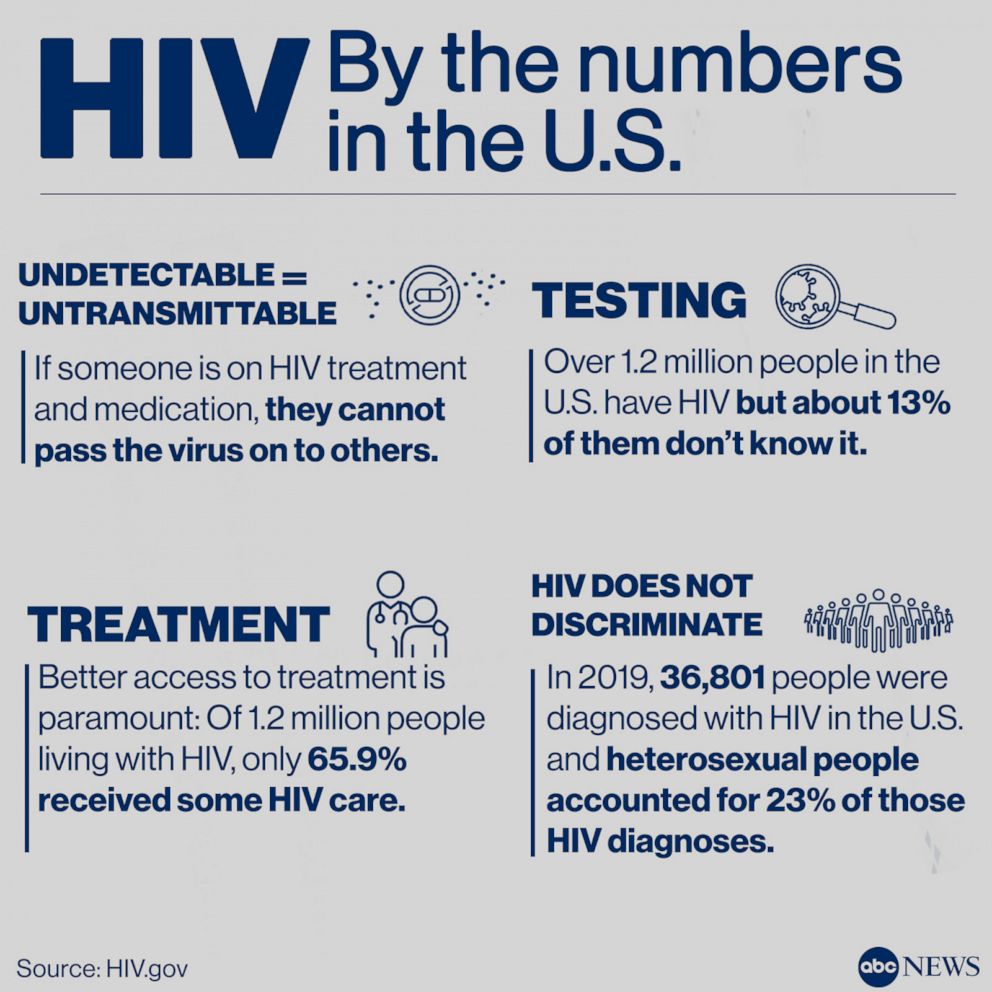

She explained to me what is now understood to be the concept of "U=U": "Undetectable = Untransmittable." Meaning, if the virus was brought down to “undetectable” levels in my body with proper medication and treatment, there would be no risk of me passing the virus to anybody else.

She also affirmed that I could live a long and normal life, contrary to the disastrous narrative in my mind.

In fact, in 2019, six years after my diagnosis, Dr. Anthony Fauci in 2019 would affirm this concept in a report and commentary, sharing that an overwhelming body of clinical evidence today firmly establishes “U=U” as scientifically sound. Clinical trials funded by the NIH now show that people living with HIV, who have an undetectable status by staying on prescribed medication, cannot transmit the virus to others.

This was and continues to be groundbreaking science. Just one pill every morning, a cocktail of three to four medicines in one, would maintain this undetectable status for me.

Incredibly, after being prescribed the proper medication, I was living undetectable just three months after my initial diagnosis and continue to be to this day.

But it was the living part that proved to be the greatest challenge of all.

In fact, my most painful memories are ones of experiences and interactions since those first doctor’s visits and countless blood draws, as I tried so desperately to resume a normal life.

Dating in particular, would never be the same. I remember the first time I shared the news with someone on a date: I earnestly thought there could be significant chemistry after a few dates, so, I felt that I had to tell them…

“Sorry, it’s just not my thing,” they eventually told me.

“That’s not something I’m really ready for,” another date said.

“What would my family think?” another responded.

I quickly mustered the courage to try a new strategy: Sharing my condition with a potential date straight away in a dating app chat, rather than waiting for the “right time” in-person.

“Yikes,” they quickly replied.

Minutes later we became unmatched on the app.

I would eventually stop dating altogether for a while because it hurt too much.

Living as an “other” in society among a community of individuals already cast out by society provides for its own set of ironies. It’s a unique experience that within the LGBTQ+ community especially, we memorialize those who have died from HIV/AIDS, but often discriminate against those who live with it.

As I reflect on that time in my life, bringing up my HIV status to a potential partner felt like a death sentence in and of itself. The truth is, there is never a “right time” to share and disclose a chronic illness like HIV with anyone, but to me, there are the right people to share it with.

My advice for those living with HIV in the shadows is to be deliberate with who you share your life with and that it’s OK to ask leading questions to help you clearly identify a safe space for sharing. And if you're so lucky to meet someone who finds you safe and trustworthy enough to confide in, I ask that you meet them with love, compassion and understanding.

We memorialize those who have died from HIV/AIDS, but often discriminate against those who live with it.

Dating over the years brought its own set of difficulties, but I found heartache and rejection all around me. I was shocked to find myself in situations where friends -- and even people I looked up to -- who would trade HIV or AIDS jokes and jabs in conversation so irresponsibly.

“Have fun on your trip! Don’t get AIDS over there,” I overheard once at brunch.

“I’m so hungover, but at least I don’t have AIDS,” came through on a group text.

“Where did your friend end up last night? He’s probably at an HIV clinic today I bet,” another giggled at a happy hour one evening.

When I wasn’t casually pointing out that AIDS and HIV were different things (as HIV can eventually lead to AIDS only if untreated), I would typically freeze up or try to change or exit the conversation. I became an expert at dodging stings and comments that made me feel less-than.

This constant stream of embarrassment, hurt, disappointment and rejection in love and in life was cutting. I felt as if the world gave me cue after cue that I was toxic and unwanted.

Looking back, it was never this virus that held me back from the life of normalcy I wanted, it seemed as though it was everyone around me that did. I buried myself deeper and deeper in shame and silence. The pain felt unbearable. For a time, I genuinely thought it would just be easier if I wasn’t part of this world anymore. And while I never acted on these negative thoughts, they have pervaded my daily life.

It was never this virus that held me back from the life of normalcy I wanted, it seemed as though it was everyone around me that did.

We have some work to do as a society to accept truth, science and reality when it comes to HIV stigma, misinformation and education. I hope that sharing experiences like mine more openly and candidly can spare whoever is dealt this card next of so much unnecessary hurt, pain and uncertainty.

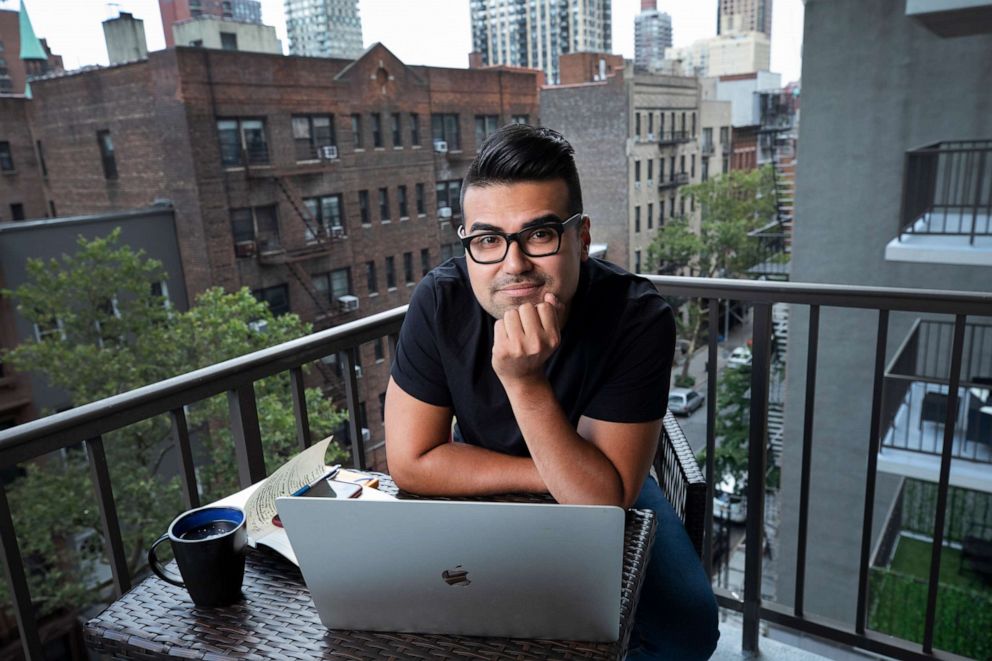

As a journalist and producer, I’ve told countless people that their story is their superpower, but despite that mantra, I have been so afraid of and vexed by my own.

Ironically, it was quarantine that granted me an opportunity for healing and for change. While in solitude, I realized that my worth was in my story all along. And it took staring into the mirror for many, many months to re-learn how to embrace all that I am, to pull me out of a life of trauma and shame.

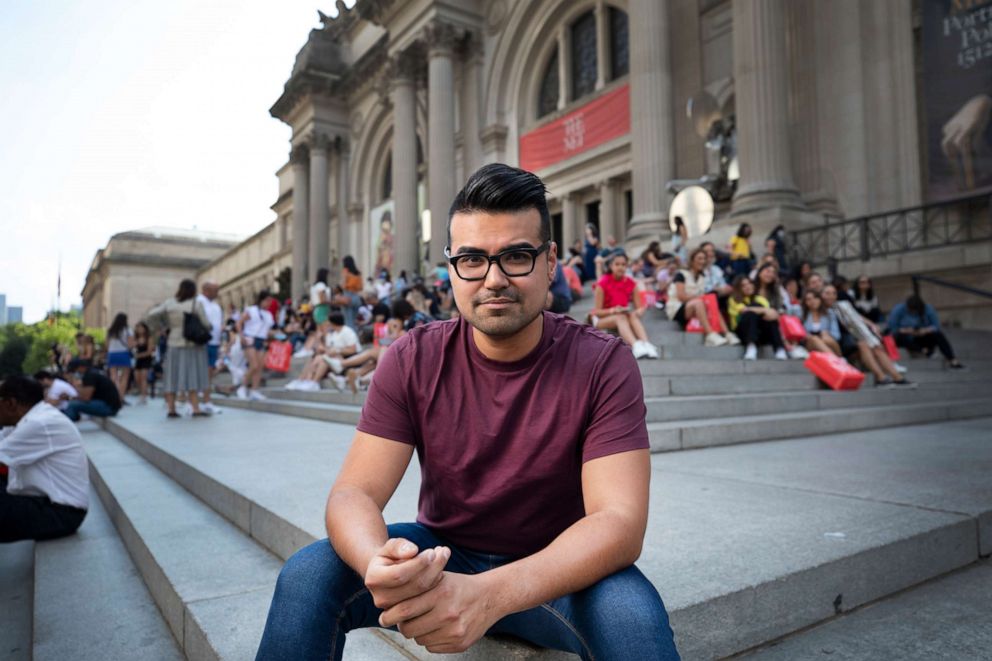

Now, on the eighth anniversary of my diagnosis, I'm sharing my truth. And I welcome the freedom it brings.

I often thought, I shouldn’t be here. But I am.

My reality is that I am not only alive, I am thriving.

But learning to thrive has been and continues to be a process.

And thriving, I’ve found too, is a choice.

You will never hear me say that I am, “HIV-positive.” You will always hear me say, “I am living with HIV.” Because living is what I’ve found I can do best. Living is what I owe to those who aren’t here with us anymore. Living is what I owe myself when I am in the darkest of places.

I refuse to sulk in shame any longer.

I’ve found that living is a duty.

And I’m choosing to celebrate life as long as I have life to live.

I’ve found that living is a duty. And I’m choosing to celebrate life as long as I have life to live.

UPDATE: Since this essay's publish, Dr. Anthony Fauci spoke one-on-one with Tony on HIV research, treatment and innovation live on Instagram. Watch the interview here:

If you or know someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.

For LGBTQ+ youth in crisis, reach out to The Trevor Project and their TrevorLifeline: 1-866-488-7386 or by texting START to 678678.