How Olympian Cullen Jones is challenging the stereotype that 'black people don’t swim'

The four-time Olympian is helping teach people of color how to swim.

Olympic athlete Cullen Jones defied stereotypes in 2008 when he became the first African American to break a long-course record in swimming in the 4x100-meter freestyle relay at the Beijing Olympic Games.

He's now working to teach more people of color how to swim, while also raising awareness about water safety.

About 64 percent of African-American children and 45 percent of Hispanic children have little to no swimming ability, according to a 2017 study by the USA Swimming Foundation.

While those numbers have decreased since 2010, drowning is still the second leading cause of unintentional injury death in all children ages 1 to 14, according to the foundation.

As for African-American children, the fatal drowning rate for kids ages 5 to 14 was almost three times higher than that of white children in the same age range between 2005 and 2009, the most recent years for which Centers for Disease Control (CDC) data is available.

"There's still at least 10 people drowning a day," Jones, 34, said. "And there’s a simple solution: swim lessons.”

Near drowning to 'Never again'

The gold medalist and four-time Olympian is all too familiar with the importance of learning how to swim. As a 5-year-old, he nearly drowned at a Pennsylvania amusement park.

“I shot out of this ride, and flipped upside down on the inner tube, and was trying to pull myself up,” he recalled. “Not only didn’t I have the strength, I didn’t have swim lessons so I didn’t know what to do at that point.”

Jones would spend the next 30 seconds underwater before being rescued by a lifeguard and getting resuscitated, he said.

“What they say is that a child can have brain damage after being underwater for that long," he said. "My mom said, 'Never again. We’re getting you swimming lessons.’”

"Fear is the number one problem"

Jones was terrified to get back in the water, he said, a feeling that keeps many people of color from ever learning how to swim.

“Hands down, fear is the number one reason, whether it’s children, whether it’s parents," he said. "Fear is the number one problem.”

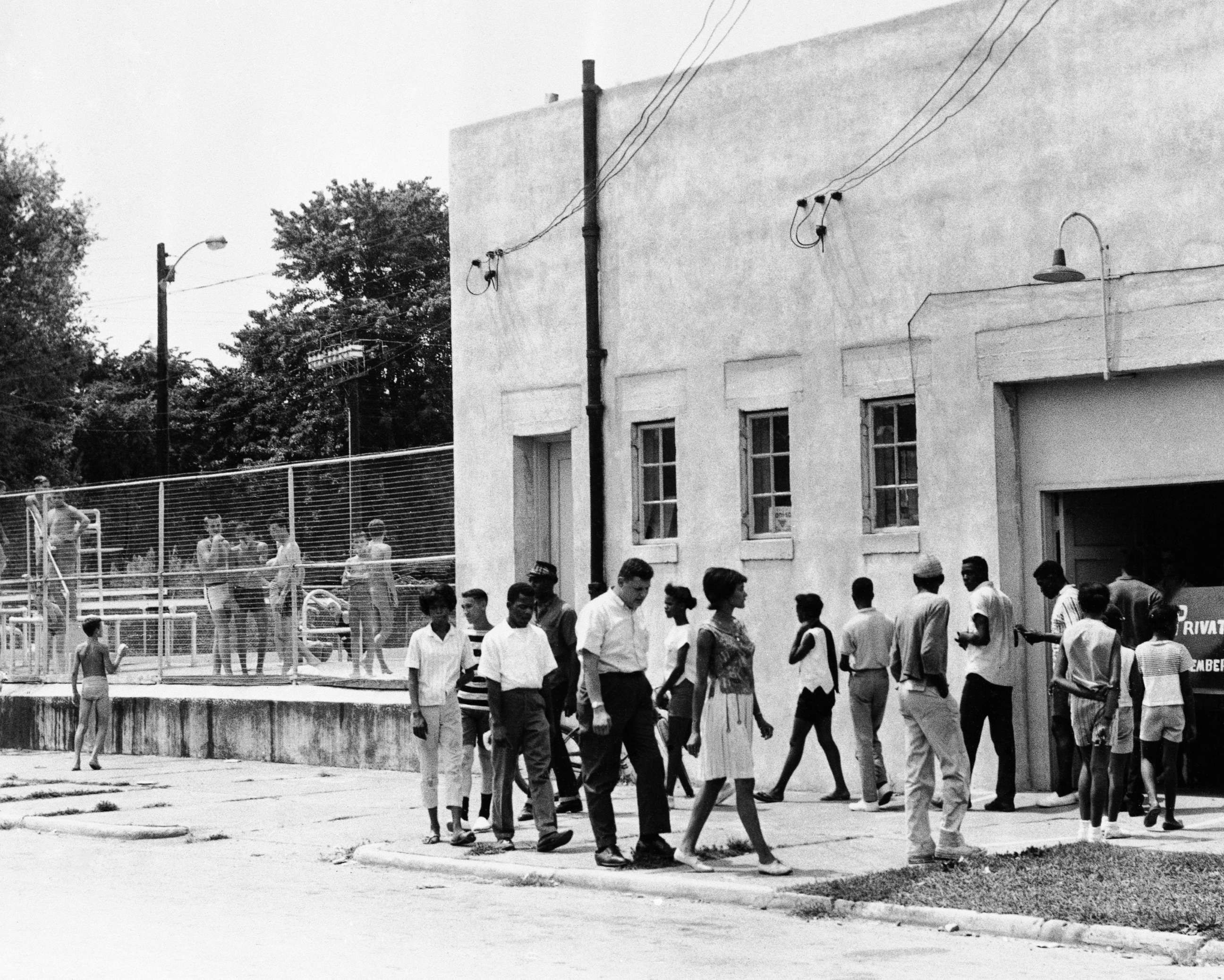

Racism at the pool

Historically speaking, stereotypes, discrimination and lack of access to pools, regardless of economic status, have kept black people out of the water, Jones said.

But it's not a thing of the past given recent incidents of alleged racism in public places and pools making headlines.

It's not only the fear of the water keeping certain people from the pools and beaches but fear of how they might be treated when they get there, Jones added.

"Pools have been a space that is very racialized,” Dennis Parker, who directs the racial justice program for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), said. "There has been a history of exclusion for people of color. .... Black swimmers were physically attacked by white swimmers in these pools.”

White people also often viewed blacks as unclean, Parker added.

"What was seen commonly in a lot of the pools was the sense of hygiene that a number of whites believed that black people weren’t as clean,” he said.

After experiencing blatant racism at pools and public spaces, Parker said he believes some parents don't want to risk putting their children in similar situations.

"If you don't have an opportunity to do something; if you have a fear to do something, it’s hard to pass on the desire to your children the thing you've been taught to fear,” he said. “So it's a legacy that gets passed on from [one] generation to another.”

Breaking racist stereotypes

The stereotypes have been cemented in U.S. black history over generations, Parker said.

Even Jones still feels the sting.

“The stigma of, ‘Black people don’t swim’ is something that bothers me,” Jones said.

“I hear this a lot: ‘I don’t float. I can’t float.’ I have four medals. I cannot float,” he said. “I went to the Olympics, twice. Cannot float. It has nothing to do with learning how to swim.”

Jones is hoping to not only change stereotypes but to save lives. Formal swimming lessons can reduce the likelihood of childhood drownings by almost 90 percent, according to the USA Swimming Foundation.

He has partnered with the organization, which provides free or low-cost swimming lessons throughout all 50 states.

“We’re not trying to get you to be an Olympic swimmer, although it can happen. You never know,” Jones said. “But it’s more about learning how to swim and being safer around water.”