1 in 10 US college students experience period poverty, report says

People who experience period poverty are more likely to suffer depression.

Period poverty, or a lack of access to menstrual products and education, affects one in 10 college students in the United States, according to a new study.

These women are also more likely to report depression than their peers, according to the study published in BMC Women's Health, a medical journal.

"We know that being unable to afford these basic needs has clear ties to mental health because it's just this idea of trying to navigate life, having to worry about, 'Am I going to be able to get through this day? I need pads, can I afford them? Do I decide to buy food or do I decide to buy [menstrual] products?,'" said Dr. Jhumka Gupta, an associate professor at George Mason University and senior author of the study. "That type of emotional load takes a toll on mental health," she said.

The study, which analyzed data from nearly 500 women enrolled in undergraduate programs, found inequities in period poverty experiences too, according to Gupta.

"Black and Latina women had the highest levels of period poverty in the last year and also immigrant and first-generation students also reported higher levels of period poverty," she said. "That's very consistent with other types of health inequities that we see."

Women, who make up more than half of the population in the U.S., are already more likely than men to live in poverty, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Women also spend an average of 2,535 days in their lifetime, or almost seven years, on their periods, according to UNICEF, which can lead to thousands of dollars spent on menstrual supplies.

One estimate, released in September, has the global feminine hygiene products market growing to $51 billion by 2027.

In addition to the monetary costs, there are also the hidden costs, like the need to take time off of work or school due to painful symptoms. Poor menstrual hygiene also poses health risks for women, including reproductive issues and urinary tract infections.

Women in the study who experienced period poverty reported borrowing products, using non-menstrual products like toilet paper, using pads or tampons longer than recommended or going without products entirely during menstruation, according to researchers.

"We know there's food insecurity in college populations. We know there's economic hardship, but this particular aspect of economic hardship, which is period poverty, wasn't looked at as much," said Gupta. "And we know that being unable to meet basic needs such as food and housing, that is clearly tied to poor mental health, poor emotional well-being,

The data analyzed in Gupta's study was collected prior to the coronavirus pandemic, but the pandemic is a situation that has made period poverty even worse, according to Gupta.

During the pandemic, women, and particularly women of color, have been the hardest hit economically. At least 275,000 women left the labor force in January, pushing the total number of women who have left the labor force since the start of the pandemic to over 2.3 million, according to the National Women's Law Center (NWLC), a policy-focused organization that fights for gender justice.

Gupta said that not only should colleges and universities tackle period poverty the same way they tackle an issue like food insecurity for students, but that federal legislators should also be implementing policy solutions, from eliminating the so-called "tampon tax" so that feminine hygiene products are not taxed, to including menstrual product coverage in COVID-19 relief legislation.

"Policy and legislation that allows for products to be more affordable can be mental health intervention," said Gupta, citing her latest research. "[Period poverty] really needs to be addressed at the national level."

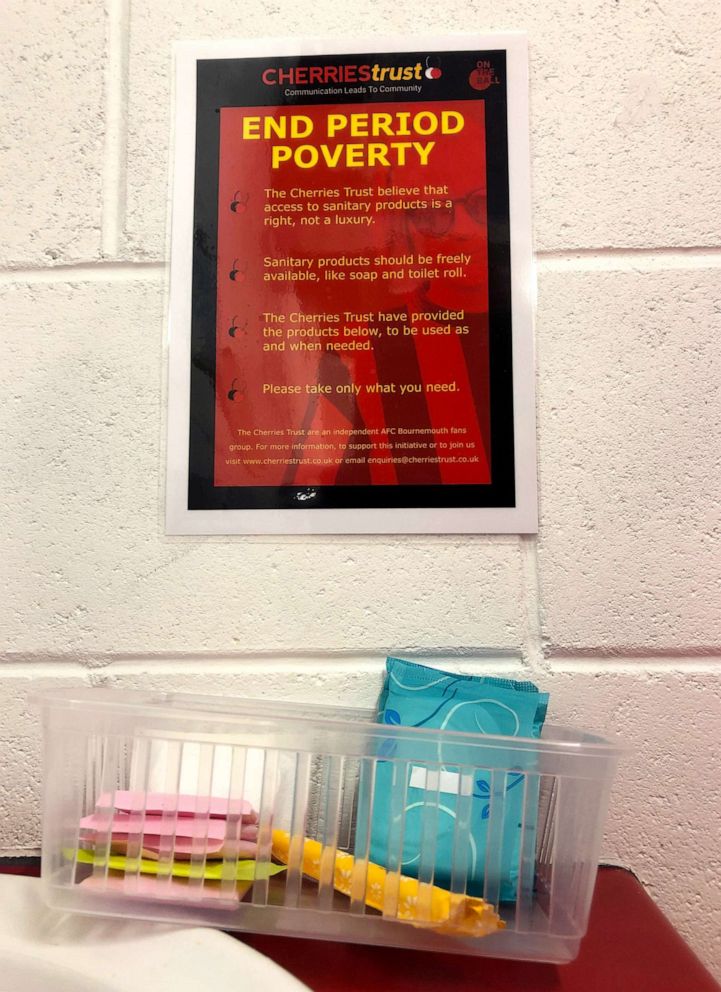

Scotland made history last year by becoming the first country in the world to provide period products to all women for free.

In addition to a nationwide program to make period products free of charge, schools, colleges and universities were also ordered by the law to make period products available for free in bathrooms.

In the U.S., Congress last year passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act that included a provision allowing people to use Health Savings Accounts (HSA) and Flexible Spending Accounts (FSA) dollars to buy menstrual products like pads, tampons, liners and menstrual cups.

Rep. Grace Meng, D-N.Y., who was instrumental in adding that provision, has also introduced several pieces of legislation to make menstrual products more accessible, from the Menstrual Equity for All Act that proposes changes like requiring corporations of 100 employees or more to provide free menstrual products to employees to the Good Samaritan Menstrual Products Act that would allow more menstrual products to be donated to and distributed by nonprofit organizations, according to Meng's website.

Meng plans to reintroduce her menstrual-focused legislation in the 117th U.S. Congress, a spokesperson told ABC News.