Breast cancer survivor shares cautionary tale of relying solely on thermography

Why the FDA says you need additional testing.

This story was updated to include elements reported on "Nightline."

When Morganne Delain discovered a lump in her breast in 2011, her first thoughts were fear. She was nervous about undergoing tests and treatments, and afraid of what a cancer diagnosis would mean.

In those dark moments, she was in denial and hoped to solve the problem without traditional cancer screening such as mammography. Instead, she turned to a brightly colored test.

Thermography is a type of infrared imaging screening used to detect heat patterns underneath the skin, mapping them into X-ray-like images of colorful waves coursing through a body. It’s often used to track blood flow, but some practitioners say it can also identify the precursors to breast cancer without any radiation exposure.

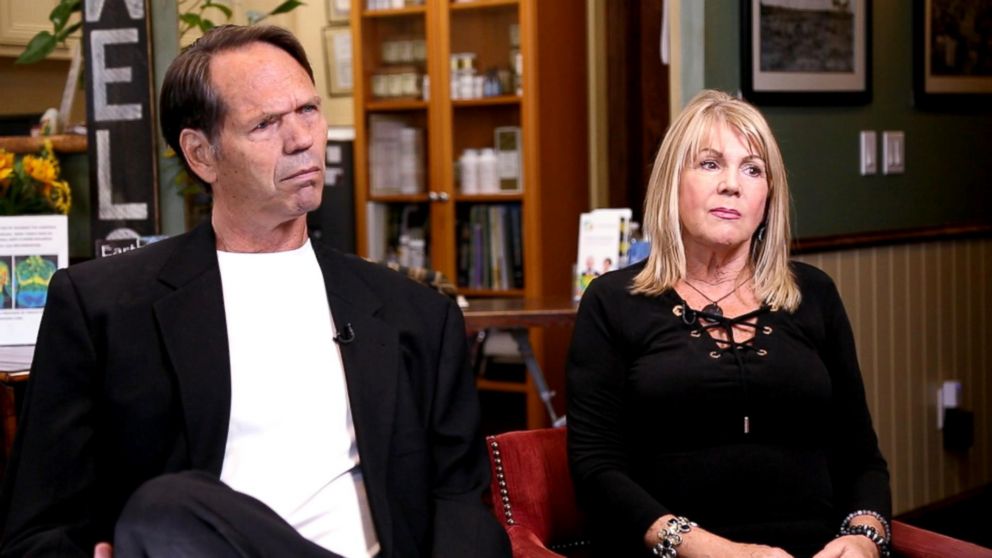

Delain says it was that claim that attracted her. A believer in homeopathic medicine, she said she was eager to find an alternative path to mainstream treatment. She went to Total Thermal Imaging Wellness Center in La Mesa, California -- a clinic run by Dr. Greg Melvin, a chiropractor, and his partner, Linda Hayes.

"They said they can detect disease maybe in advance, before it even happens."

Melvin and Hayes say they make it clear to their clients that thermography is not a replacement for mammography, but Delain said she didn't notice that in the fine print.

“They said they can detect disease maybe in advance, before it even happens,” Delain said.

After Delain underwent a scan, Melvin analyzed her results.

“He said, ‘Are you sure you have a lump?’” Delain recalled. “And I said, ‘yeah.’ And then he looks back at the thermal imaging, ‘I don’t see anything.’”

Delain said she was relieved.

“I don’t have cancer then,” she remembers thinking.

Her baseline report indicated she had a “mild to moderate risk of developing aggressive tissue.” Melvin recommended exercises, a cleanse and that she come back in three months for a comparative scan, his protocol for new patients.

But Delain said an uneasy feeling still lingered over her. When she returned to Total Thermal four months after her initial scan, her symptoms had grown dramatically worse.

“All of the sudden, I just said, ‘I’m such a fool. Why did I even come here?’” Delain said, adding that she refused another set of scans.

In an interview, we showed Melvin Delain’s report from 2012. He said he did not remember Delain, but that her report displayed “significant findings.” When asked why he didn’t make an immediate referral with those findings, he said that they must wait three months to do a comparative scan to understand the results.

Melvin later told ABC News via email that Delain didn’t follow his recommendations, did not return for a follow-up to the initial examination in three months and pointed out a line at the bottom of the intake form: “The report will not tell me whether I have an illness, disease, or other condition.”

Unemployed and uninsured, Delain said it took her several more months to get an appointment for a mammogram, and then a biopsy, and then a diagnosis: Stage 3 breast cancer.

A diagnosis in need of a cure

Thermography is approved by the FDA for breast cancer screening, but only when used with what the administration considers a primary test, like mammography. A mammogram -- a low-dose X-ray image of the breast -- is considered by medical professionals to be the gold standard for screening for breast cancer.

“Patients who undergo a thermography test alone should not be reassured of the findings,” a public statement issued by the FDA in 2017 reads. “Thermography has not been shown to be effective as a standalone test for either breast cancer screening or diagnosis in detecting early stage breast cancer."

According to an article titled “Harmonizing Breast Cancer Screening Recommendations: Metrics and Accountability” published in the American Journal of Roentgenology, “The American Cancer Society states that no study has ever shown that it is an effective tool for detecting breast cancer. Both the American College of Radiology and the Society of Breast Imaging (SBI) do not endorse thermography for detecting clinically occult breast cancer.”

But in 2018, Hayes allowed ABC News producers to film her pitch at a business expo. Hayes told them “no one needs a mammogram,” regardless of whether they’ve had a thermal reading. A brochure she distributed at the event advertises thermography as a first and potentially life-saving step toward detecting cancer. “Share with your friends & family that there is an alternative to mammography that ... is far more efficient at detecting cancer,” it reads.

Dr. Len Lichtenfeld, the acting chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society, is skeptical of these statements.

"People have looked at thermography as an early detection tool. The data just doesn't support it as being effective."

“I don't know anyone who I consider a credible resource or expert who would suggest that thermography in the absence of a mammogram or another breast cancer detection test is adequate to save lives,” Lichtenfeld said.

After the interview with ABC News, Total Thermal said that it changed its brochures.

When thermography wasn't enough

“People have looked at thermography as an early detection tool. The data just doesn't support it as being effective,” Lichtenfeld of the American Cancer Society said. “You have to show that it works. Otherwise, you end up in situations where people believe it, they don't get the test that's been proven to be beneficial, and the results may speak for themselves.”

Alma Arciniegas’ family said the result of her reliance on thermography was devastating. She went to a different thermography practitioner in Northern California that is not affiliated with Total Thermal Imaging.

“She told me after, very excited, ‘Oh, I went and got checked out. All clear,’” her son Camillo Mejilla, 25, remembered.

But six months after her screening, she received the same diagnosis as Delain -- Stage 3 breast cancer. However, her prognosis was much worse.

The cancer quickly spread to Arciniegas’ brain, severely limiting her ability to talk and perform other basic tasks.

Mejilla watched as his vivacious mother became feeble. She struggled to climb the stairs and became unable to answer even simple questions.

She was 55 when she died in 2015.

Her friend and attorney, Robert Cartwright, said he believes she didn’t have to lose that fight.

“Alma would be here with us today if she had not relied on the results of her thermogram,” he said.

Before Arciniegas died, she sued her thermography clinic and the manufacturer of the thermal imaging camera it used. The case was eventually settled, with the defendants denying any wrongdoing.

“Despite the fact that she couldn’t talk much, she could say, ‘I love you,’” Mejilla recalled, adding that those were the last words she said to him.

Delain, meanwhile, endured years of surgeries, chemotherapy and radiation after her diagnosis. But she said those dark days revealed internal fortitude.

“I think I’m just stronger than I thought I was, because I’m standing here now,” she said.

Delain is now cancer free and has this advice for anyone who finds themselves in her situation: “Get a biopsy. It’s the only way.”

Doctors may not always perform a biopsy on a lump in the breast, depending on such factors as the woman’s age and other risk factors, but it is important to listen to your body when something feels wrong, and to see a doctor and consider seeing a second to get an additional opinion.