Doctor calling for FAA, Southwest changes after midair scare

"It was so scary, I felt terrified and scared for my life the entire time."

Following a mid-air scare, a doctor is calling for the Federal Aviation Administration to make policy changes and for Southwest Airlines to stock lifesaving epinephrine auto-injectors aboard passenger planes.

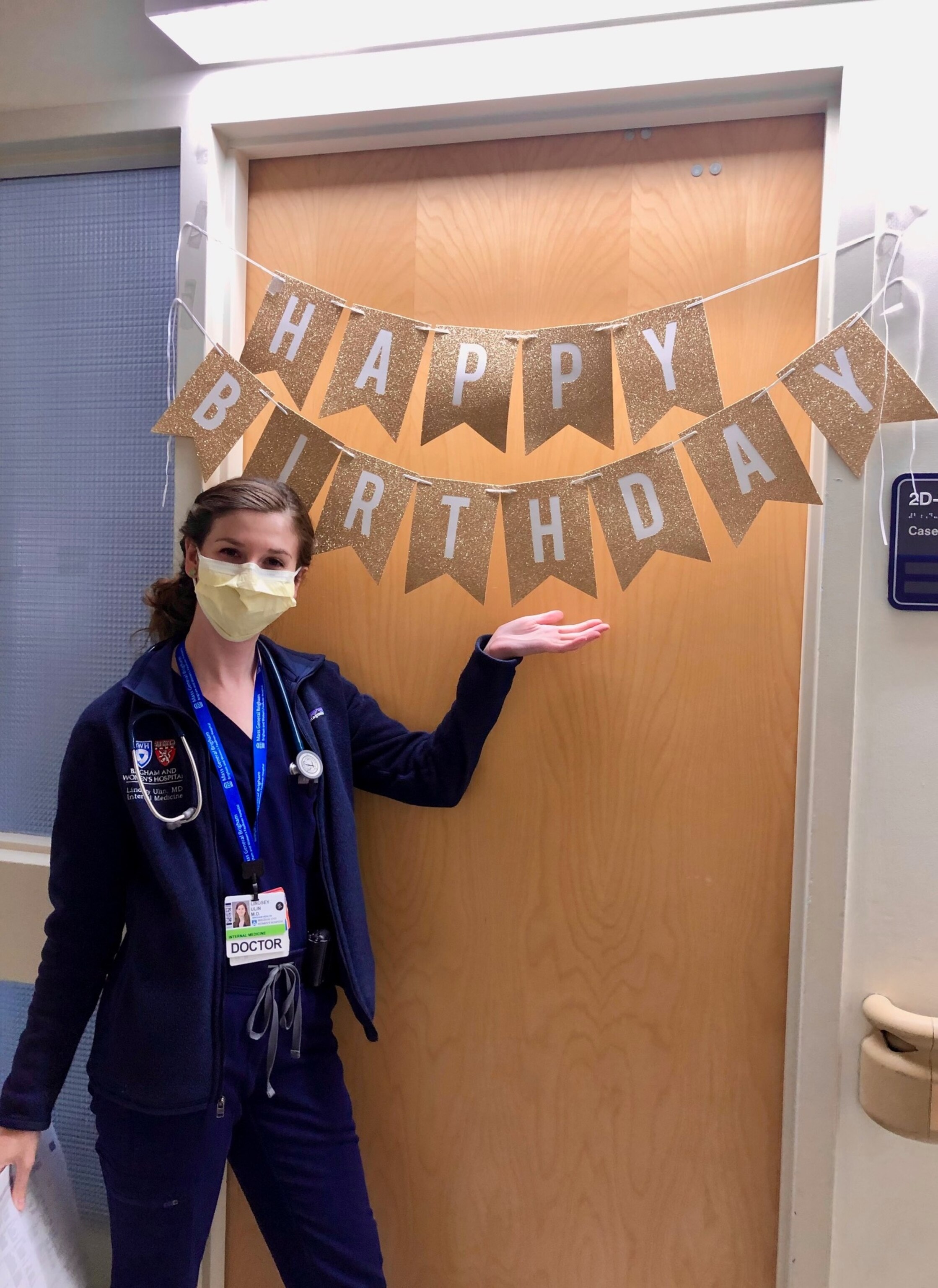

Lindsey Ulin, an internal medicine resident physician at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, was on vacation in March and traveling with her mother and sister on a Southwest flight from Phoenix, Arizona, to Austin, Texas, when she said she experienced anaphylaxis -- a severe allergic reaction -- for the first time.

Ulin said she'd had a burger with fries and Brussels sprouts at the airport beforehand and suspects the meal was likely the culprit for her allergic reaction, during which she said she developed hives and had trouble breathing.

"It was so scary, I felt terrified and scared for my life the entire time. It was also frustrating because, as a doctor, I immediately recognized what was happening to me," Ulin told "Good Morning America."

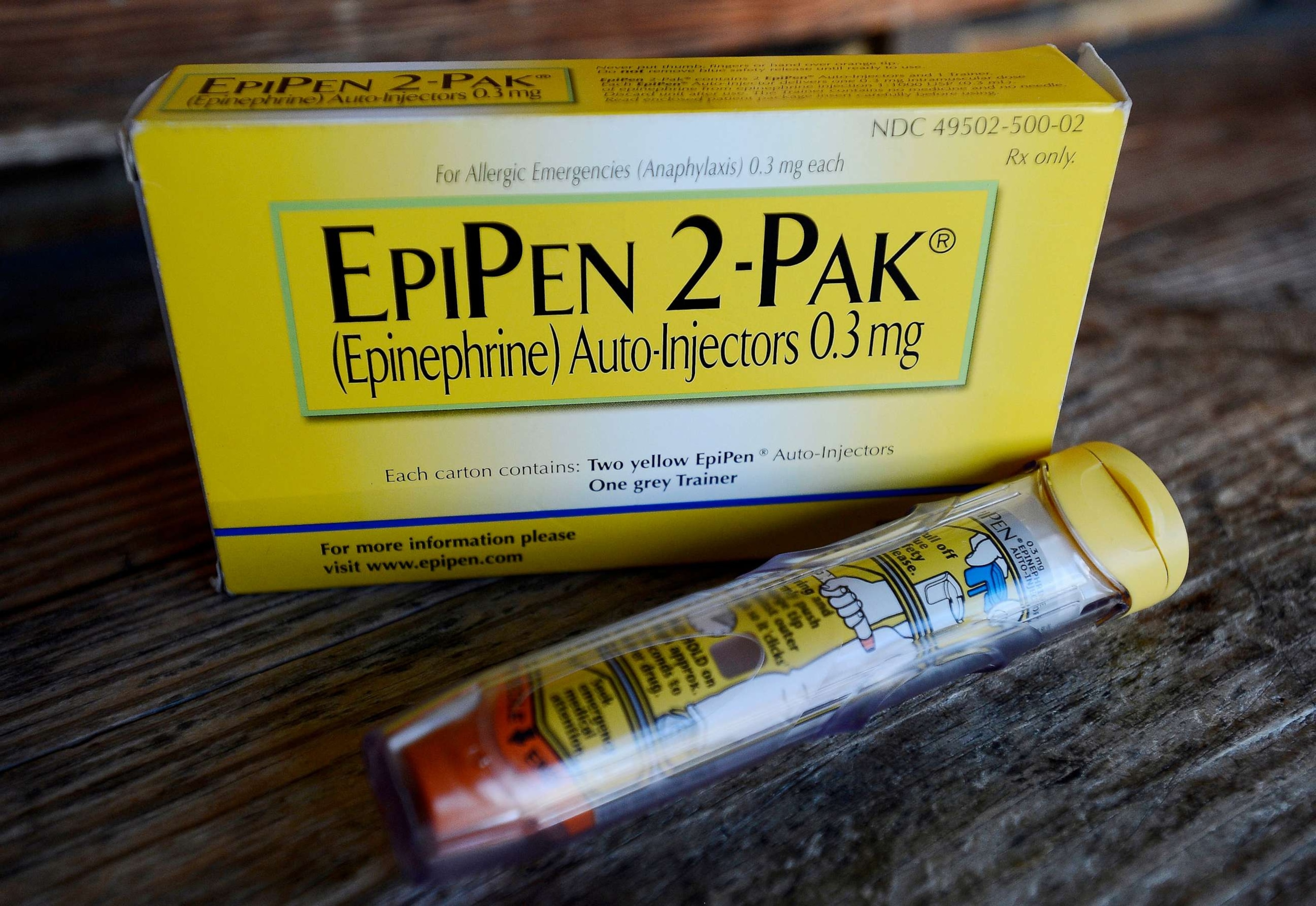

According to Ulin, when she called for a flight attendant for assistance, she learned the in-flight medical emergency kit didn't have what she needed -- an epinephrine auto-injector, commonly called by the brand name "EpiPen." The device is pre-filled with epinephrine, a prescription medication, and is designed for easy use since there is no need to measure the dosage amount.

"I was still able to speak a little bit at this point. Not very well, but enough to say, 'EpiPen,' and that was when he told me that Southwest does not carry EpiPens on board," Ulin recalled, adding that no one else on board appeared to have any on hand either after a flight announcement was made.

"Things were still getting worse, and in that moment, I knew that I was very close to dying -- and my family was having to sit there helplessly [and] watch it happen," Ulin said.

It was another doctor on the same flight that Ulin said came to her rescue, administering epinephrine from the medical kit on the Southwest flight.

"I can't even describe it, just how much it meant when somebody showed up and said, 'I am a doctor. I'm going to help you.' And I would not be here today if he hadn't been on the flight. Because the kind of [epinephrine] that Southwest carries in their emergency kits is incredibly difficult to use," Ulin said.

Ulin said because the epinephrine was in an ampoule and not in an auto-injector format, it took multiple steps and a trained medical professional to be able to administer a safe amount of the drug. When in an ampoule, the correct amount of epinephrine would need to be measured out and transferred into syringes before use, according to Ulin.

"[The other doctor] was able to dig in the emergency kit, find parts of a syringe to be able to get the [epinephrine] out of the ampoule. But then, it has to be transferred to a different kind of syringe to be given intramuscularly, which again, is another step in a very long and potentially dangerous process," Ulin recounted.

Dr. James R. Baker Jr. is the director of the Mary H. Weiser Food Allergy Center at the University of Michigan. Baker was not on Ulin's flight or involved in her case but said in his view, it was likely "not an appropriate thing to have [Ulin] trying to treat themselves by trying to figure out how much epinephrine they need to draw to treat their own reaction."

After the flight landed, Ulin said she was met by emergency medical services and given another dose of epinephrine before being transported to a local hospital for more care. Ulin said she had to get three doses of epinephrine and has not had another anaphylactic reaction since then.

Allergic reactions while flying can occur but according to a 2018 JAMA review, only about 1.6% of in-flight medical emergencies are due to allergic reactions, a statistic the FAA cited in its own 2018 study of allergic reactions, which concluded allergic reactions are rare occurrences. The agency also noted that "current contents of [emergency medical kits] are being reviewed for potential modification."

Over a month since the incident, Ulin said she feels "lucky" with how her experience ended and is now speaking out and urging the FAA and Southwest to make changes she said will prevent others from going through what she had to endure and save lives.

"I'm advocating for the FAA to update their requirements for airlines in the emergency medical kits, which they haven't done in almost 20 years and is long overdue, but that must include epinephrine auto-injectors, such as an EpiPen," Ulin said.

"I am also calling for Southwest to make this change within their own company because I believe they can do it faster than the FAA will be able to enact this legislation. And this is a matter of life and death and can't wait any longer," Ulin added.

Ulin said she has written to Southwest and also tweeted at the FAA since her experience but has not yet received a reply.

When reached by "GMA," the FAA noted that air carriers are not allowed to take off without epinephrine ampoules and syringes in flight kits and said any changes to kits would need to undergo a rulemaking process.

"A commercial flight cannot take off without a complete, sealed Emergency Medical Kit. The FAA requires many items to be carried in emergency medical kits, including epinephrine," the federal agency said via email.

The agency added, "The kits are meant to be used by flight attendants. Flight attendants are trained on emergency procedures, including use of medical equipment."

Southwest also told "GMA" in a statement that "our aircraft are outfitted with onboard medical kits that adhere to all FAA regulations, including carrying epinephrine in two concentrations. The Safety and Comfort of our Customers is Southwest's top priority and we're continually looking for ways to improve our inflight Customer Experience."

Food Allergy Research and Education, a nonprofit focused on food allergy advocacy, said the issue of allergic reactions on flights has been a longtime problem impacting millions who have food allergies.

"This has been a very serious issue for years, as incidents like what happened on Southwest occur on a fairly regular basis. It has been going on for more than a decade," the organization told "GMA" via email.

"Very small progress has been made on making airline flying safer related to the administration of epinephrine. FARE in 2019 helped lead the effort by filing a lawsuit with [the Department of Transportation] over allowing early boarding for food allergy families, but even this rule is routinely ignored," FARE added.

In 2019, the DOT decided that those with food allergies could be considered as having a disability and could therefore pre-board a flight to wipe down seating areas before a flight took off.

Baker said one of the reasons airlines don't stock EpiPens is likely due to high costs.

"The reason epinephrine in auto-injectors are not routinely stocked on planes is that they're given very short shelf lives. So in fact, they have to be replaced continuously and they cost much, much more than regular epinephrine. The fact that the airlines would have to … go in and replace the auto-injectors in these kits, and the expense of that really precludes a lot of airlines from doing this," Baker told "GMA."

How to respond to a severe allergic reaction

When people go into anaphylactic shock, both Ulin and Baker agree the "only effective drug is epinephrine."

"Anyone who has a serious food allergy and has had a prior episode of a systemic allergic reaction should have an EpiPen and keep one with them all the time because you never know when you're going to encounter a food that might be cross-contaminated or problematic," Baker said.

"Often, especially with adults, if you get a reaction, it's in a public place or a restaurant where you could be fed things that you normally wouldn't eat. And in fact, because they're cooking multiple different meals at the same time, there's a higher incidence of cross contamination that potentially could cause an allergic reaction," he added.

Since her scare, Ulin herself said she now carries four EpiPens in case of a future reaction.

There is no formal recommendation for the number of epinephrine auto-injectors one should keep on hand, but some people may need more than one in the event of a severe reaction. A 2010 study in the journal Allergy and Asthma Proceedings showed that 17% of patients who visited an emergency room due to food-related anaphylaxis needed more than one dose of epinephrine in their treatment.

The branded EpiPen is sold in a pack of two.