Will people with Down syndrome unlock the mystery of Alzheimer's disease?

A clinical trial is underway for a vaccine for Alzheimer's disease.

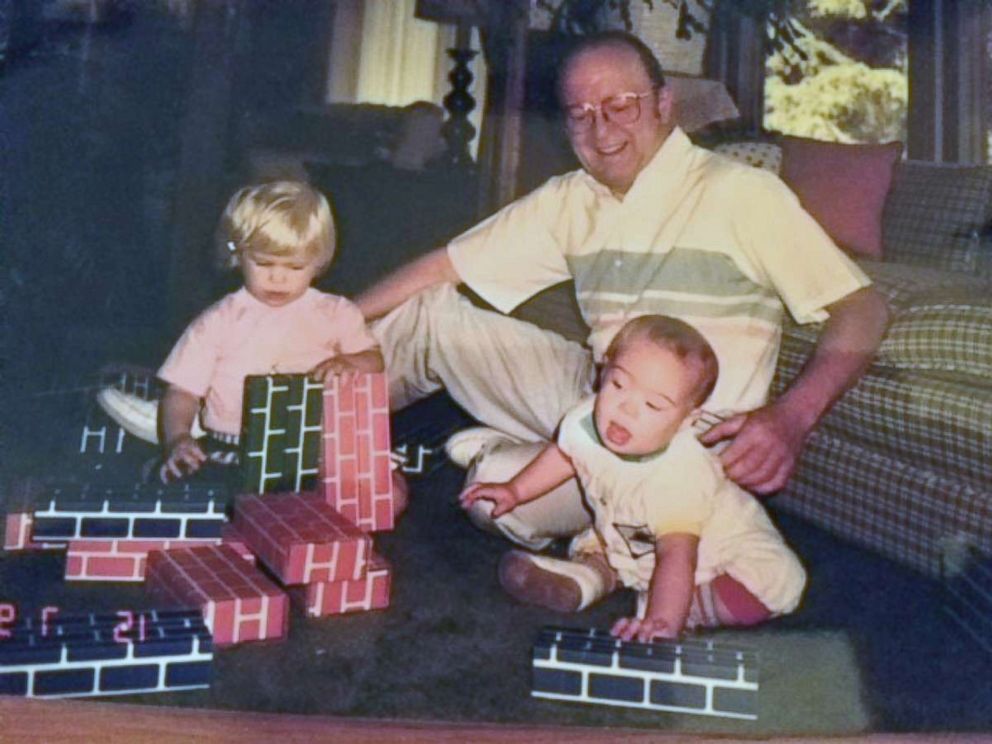

Michael Clayburgh has a long family history of Alzheimer’s and his grandfather died from the disease.

Clayburgh is now on the front lines of unraveling the causes of the disease that has so devastated his family because of a condition he carries -- Down syndrome.

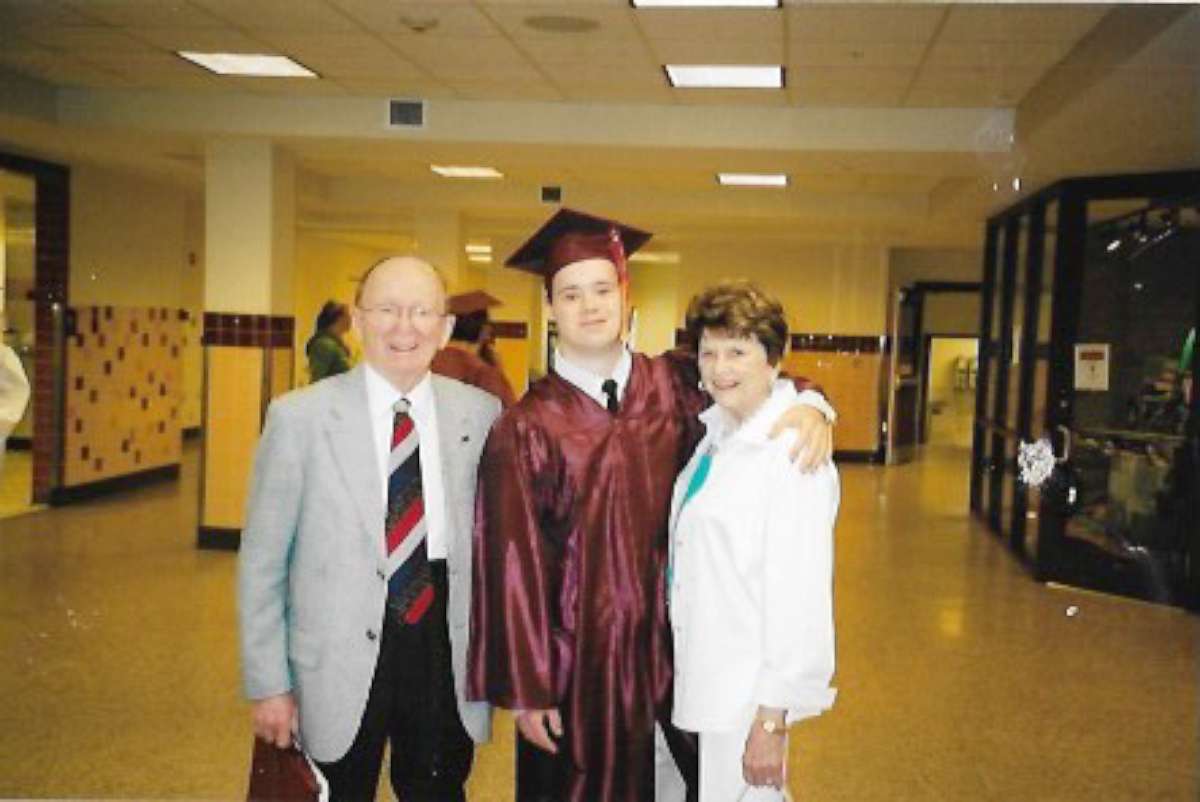

The 29-year-old from New Hampshire is participating in a clinical trial for a vaccine that would prevent Alzheimer's from forming in the brains of people with Down syndrome.

"My name is Michael Clayburgh and I like the study," he told "Good Morning America."

“Michael is very aware of Alzheimer’s because we’re surrounded by it,” added his mother, Nancy Clayburgh. “He understands it and understands that his grandfather died from Alzheimer’s and knows he can be involved and help find a cure.”

People with Down syndrome seem to have a double risk: They are more susceptible than the average population to Alzheimer’s disease and struck by it earlier in their lives.

Around 40 percent of people with Down syndrome develop Alzheimer's-like symptoms by age 40 and 50 percent develop symptoms by the age of 50, according to Dr. Brian Skotko, a medical geneticist who is leading the clinical trial at Massachusetts General Hospital.

"Every family that I know that has a person with Down syndrome is well aware of that statistic," said Nancy Clayburgh. "It's a great concern."

How are Down syndrome and Alzheimer's connected?

The connection between Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s might lie in a gene.

People with Down syndrome are born with an extra copy of chromosome 21.

Chromosome 21 carries what is known as the APP gene. APP overexpression leads to a buildup of plaques in the brain.

Plaque buildup in the brain interferes with how brain cells function and increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

"Right now we believe that people with Down syndrome might have the key to unlock the mysteries of Alzheimer's for all of us," Skotko said. "The pathology of their brains resemble Alzheimer’s at an earlier age and can be studied."

Skotko has a personal reason for devoting his career to unlocking the mystery of Alzheimer's. He has a sister with Down syndrome.

"She’s 38 years old and she has such a robust life and she’s the life coach for all of us," he said. "I am really motivated and want to do everything I can as a brother, but also as a clinician so that there will be something clinically available so that she does not have to get Alzheimer’s."

Unlocking the mystery of Alzheimer's

Skotko and his team of researchers at Massachusetts General, a Harvard University teaching hospital, are participating in the two-year clinical trial that Clayburgh is part of. The overall efforts are coordinated by the University of California San Diego.

As is the case in most "gold standard" medical trials, neither the participants nor the doctors know who is getting the real vaccine for Alzheimer's disease and who is getting the placebo. That doesn't stop participants from wanting in.

"This is two years of being dedicated to a research trial where you don't even know whether you're actually getting the vaccine," Skotko said. "And our phones were ringing off the hook when we opened the trial."

There are just over 200,000 people in the United States with Down syndrome. Around one in every 700 babies are born with the chromosomal condition, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Alzheimer's, a disease that leads to memory loss and dementia, affects more than 5 million Americans, according to recent government estimates.

There is no treatment currently for Alzheimer's disease itself. Patients can only be treated for their symptoms, which in Down syndrome patients include seizures and irritability, among others, according to Skotko.

If it works the way they hope it will, the vaccine in this clinical trial would prevent Alzheimer's from forming in people with Down syndrome by stimulating their immune system to prevent plaque buildup in the brain. The vaccine is made by AC Immune, who is co-funding this trial along with the National Institute of Health and the LuMind Resarch Down Syndrome Foundation.

"We have known about the connection between Down's syndrome and Alzheimer's for several decades, but it's only recently that scientists are beginning to unravel why that is on a molecular basis," Skotko said. "That is allowing us to translate it into real clinical trials."

Researchers in Germany are testing the vaccine on people without Down syndrome, too, according to Skotko.

Should the vaccine continue to pass through the clinical trial process without any issues, it will take 10 to 15 years to get to market in the U.S. And no one, at this point, is talking about how much the vaccine would cost.

A race to a cure

For families like the Clayburghs, a drug that could prevent Alzheimer's cannot arrive soon enough.

"Now Michael is 29 and you can start to see some signs [of Alzheimer's] in their 30s and 40s so you try to make yourself aware of their behaviors," said Nancy Clayburgh. "It's always in the back of your mind."

Michael Clayburgh currently works three jobs and volunteers at a local hospital and with the local police department.

"Michael works really hard and [his jobs] means a lot to him," said Emily Casian, Michael's job coach. "Finding a cure [for Alzheimer's] would be a great thing."

Skotko said he has "never been more hopeful" for the Clayburghs and other families with a loved one with Down syndrome.

"Parents are so eager to do anything to make sure that their person with Down syndrome who's achieved so much, who has accomplished so much, doesn't lose it to Alzheimer's," he said. "Now we have better medicine, better science and better investments in making tomorrow better than it is today."