COVID-19 virus origin likely animal to human transmission; concerns about WHO report linger

Scientists have more evidence, but we may never know exactly what happened.

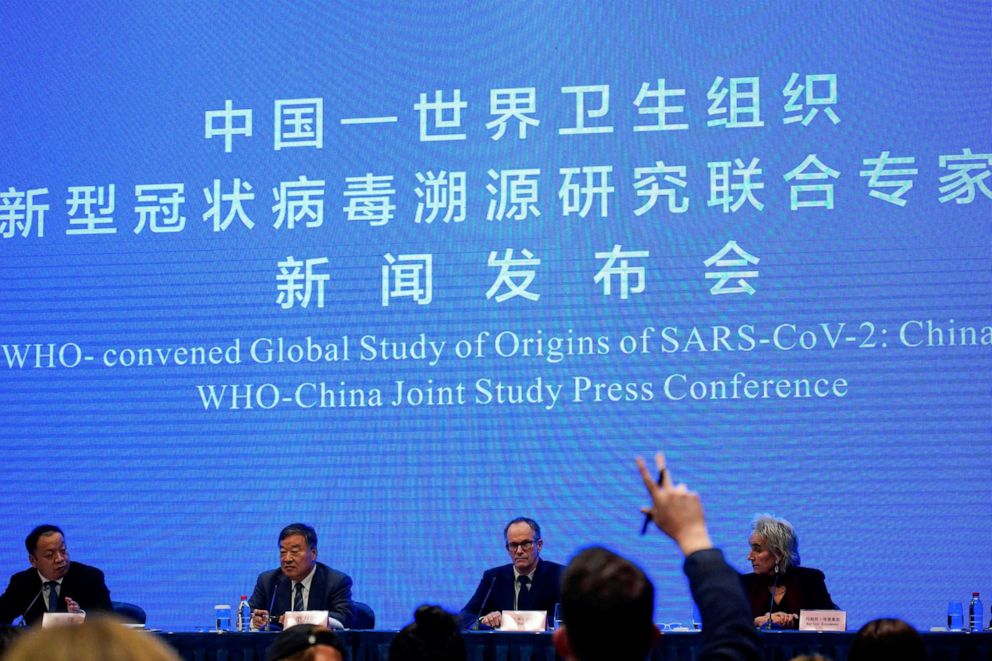

The World Health Organization and China released a long-awaited joint report into the origins of COVID-19 on Tuesday, pointing to transmission from bats to another animal and subsequently to humans as the most likely way the pandemic began. At the same time, the United States and 13 other countries raised concerns about the report in a joint statement, arguing that the WHO team was "significantly delayed and lacked access to complete, original data and samples."

The review, which was conducted by a WHO team of international experts in Wuhan, China, between Jan. 14 and Feb. 10, is considered a first step in what will likely become a years-long investigation into the virus' origins.

Many of the report's conclusions were already discussed during a press conference back in February, at the conclusion of the weeks-long investigation.

"This report is a very important beginning, but it is not the end," Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the WHO, said during a Tuesday press conference in Geneva. "We have not yet found the source of the virus, and we must continue to follow the science and leave no stone unturned as we do."

The joint statement from the United States and other countries noted that their governments are concerned about the report in regards to access, transparency and timeliness, stating, "Scientific missions like these should be able to do their work under conditions that produce independent and objective recommendations and findings."

"Together, we support a transparent and independent analysis and evaluation, free from interference and undue influence, of the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic," the statement read. "In this regard, we join in expressing shared concerns regarding the recent WHO-convened study in China."

Although the report did not contain any startling new revelations, Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, director of Columbia University’s Center for Infection and Immunity, called the report "extraordinarily detailed and exhaustive." While scientists previously believed several transmission pathways for the virus to be most probable prior to the Wuhan trip, there's now data to substantiate those theories.

"First and foremost is the idea that this originated in a bat and moved through some intermediate host that allowed it to adapt and become better capable of infecting humans," Lipkin said.

Reaching a definitive conclusion about the virus' origins might take years, or might not be possible at all. "You're trying to reconstruct events from a year and a half ago with incomplete sampling and data," Lipkin explained. "We may never know exactly what happened."

If previous infectious disease investigations are any clue, the virus' origins could remain shrouded in mystery. Researchers pointed to the 2003 SARS outbreak, which was caused by a close cousin of the virus that causes COVID-19 and eventually traced back to a single population of horseshoe crab bats.

But that search took more than five years. "I think they were quite lucky," Vincent Racaniello, a microbiology and immunology professor at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons, said of the SARS investigation.

"We've still not found the source of Ebola virus outbreaks after many years of looking," he added. "It's not easy."

In the WHO-China report, the authors investigated four possible pathways through which the virus could have emerged:

I. Direct transmission from animals to humans: 'Possible to likely'

Also known as zoonotic spillover, this theory suggests that SARS-CoV-2 was passed directly from an animal, most likely a bat, to humans. This transmission could have happened through farming, hunting or other close contact between humans and animals.

II. Transmission to humans through intermediary animal host, such as a pangolin: 'Likely to very likely'

This theory proposes that the virus was transmitted from an original animal host to an intermediate host, such as a minks, pangolins, rabbits, raccoon dogs, domesticated cats, civets or ferret badgers, and then directly infected humans through live contact with the second animal.

III. Introduction to humans through the frozen food chain: 'Possible'

The "cold-chain" theory suggests that transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from animals to humans might have happened through contaminated frozen food. A frozen food product contaminated with animal waste that contained SARS-CoV-2 could have transferred the virus to humans without any direct live contact between humans and animals.

IV. A laboratory accident: 'Extremely unlikely'

This highly political theory, which was previously rejected by experts at the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, proposes that SARS-CoV-2 escaped a laboratory in Wuhan through negligent biosafety practices.

The team ranked the four scenarios in order of likelihood, finding that spillover virus transmission via an intermediary animal was "likely to very likely." Direct transmission from bats to humans was "possible to likely." Virus introduction through frozen animal products or foods was considered to be "possible."

A laboratory origin of the pandemic was "extremely unlikely" and the only one of the four scenarios that the team did not recommend scientists investigate further.

While the lab leak remains the least likely hypothesis, "I do not believe that this assessment was extensive enough," Tedros said Tuesday. Further data and studies will be needed to reach more robust conclusions, with additional missions involving specialist experts, which Tedros said he was ready to deploy.

Huanan seafood market likely a 'super spreader' event, but not ground zero of the outbreak

While many early cases of COVID-19 were connected to a seafood market in Wuhan where animal products were sold, the report found that a similar number of cases were associated with other markets, or no markets at all. Extensive testing at the Huanan seafood market found no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in those animals. However, viruses from some of the Huanan market cases were identical, the report detailed, suggesting the market contributed to spreading the virus -- an early super spreader event -- even if it did not originate there.

"No firm conclusion therefore about the role of the Huanan market in the origin of the outbreak, or how the infection was introduced into the market, can currently be drawn," according to the report.

While the new report is important, Racaniello said, "It doesn't change much, except to tell the people who have conspiracy theories or accident theories that it's not true." People who don't study viruses may not realize that there's a common and predictable link between animals and viruses in humans, Racaniello explained.

"This investigation is not done," said Dr. Angela Rasumssen, a virologist and affiliate at the Georgetown Center for Global Health Science and Security and incoming research scientist at VIDO-InterVac. "Sometimes it takes years and sometimes you may never find the actual source."

In lieu of immediate answers, it will be tempting for many to "put the blame somewhere," including a tantalizing but ultimately far-fetched lab-leak theory, Racaniello said.

"Part of being a scientist is you get comfortable with some things never being explained," Rasmussen said. "But I think the general public is not, especially when it's about something that is impacting our lives so profoundly."

ABC News' Sasha Pezenik and Christine Theodorou contributed to this report.