Some have no COVID symptoms: Could the common cold be a reason?

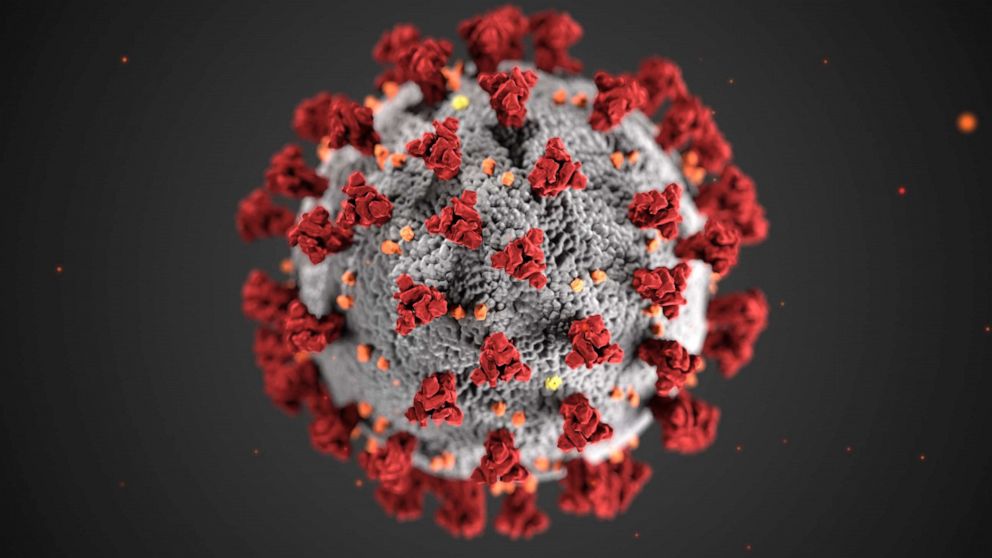

Some infected with the novel coronavirus never develop symptoms.

Some infected with the novel coronavirus never develop symptoms. Others get very sick and die. Seven months into the pandemic, scientists are racing to find out why.

There are theories. One theory is that prior exposure to other viruses may help fight off the novel coronavirus. There are four other, far less deadly coronaviruses which cause the common cold.

Earlier this summer, researchers from La Jolla Institute for Immunology published new findings in the journal Cell, offering insight into how human immune systems respond to COVID-19. When people who were previously infected with COVID-19 were exposed to the virus again, their immune system had a strong response because it already knew what the virus looked like.

But what researchers also found was that in around 40 to 60% of those who had never been exposed to COVID-19, their immune systems also had a strong reaction. The researchers said it's possible that human bodies may "recognize" the novel coronavirus because of prior exposure to its close cousins -- the coronavirus strains that cause the common cold.

"Immune reactivity may translate to different degrees of protection," said Dr. Alessandro Sette, professor at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology and a lead author on the study, in a press release.

It's possible, Sette said, that your prior infections with the common cold could give your immune system a boost, making it easier to fight off the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Many viruses fall under the coronavirus category, including ones that cause the common cold, SARS and MERS.

A study in Science published early August looked at blood samples obtained before the COVID-19 pandemic was discovered. Isolating immune system cells from those samples, scientists found that those cells reacted similarly to the COVID-19 virus as well as to four other coronaviruses known to cause the common cold.

"This could help explain why some people show milder symptoms of disease while others get severely sick," said Dr. Daniela Weiskopf, a research assistant professor at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology and one of the lead researchers, in a statement.

While these results are intriguing, viruses and immune system cells behave differently in the laboratory compared to the human body, and some physicians are awaiting additional research before embracing these findings.

"This may be part of the answer," said Dr. Simone Wildes, an infectious diseases physician and medical contributor for ABC News. "I don't know if there has been a lot of support for this yet. We still need to do some more research."

And while almost everyone has had a cold at least once in their life, COVID-19 still affects some people more severely than others. That reason may have more to do with genetics, than previous exposure to the common cold, some experts say.

"People have this idea that we are all pretty much the same. But there is huge variation in our genes in the human population," said Dr. Vincent Racaniello, Higgins professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Columbia University. "Everyone is genetically different. You can find kids who get respiratory infections 10 to 12 times a year, totally atypical. And when you look at their genome, you find that they have mutations that make them more susceptible."

Meanwhile, some scientists say the differences in the way people fare once infected could be chalked up to ailing immune systems among the elderly.

"What we know is that as you age your immune system degrades. It's called 'immunosenescence.' You are not able to control infections like you were used to. So the infection goes a little bit crazy at the beginning. You overreact and you get very sick," said Racaniello.

In the meantime, researchers continue to look at the immune system for answers to fighting COVID-19.

Jonathan Chan, M.D., is an emergency medicine resident at St. John's Riverside Hospital and a contributor to the ABC News Medical Unit.ABC News' Sony Salzman contributed to this report.