Delta variant: 5 things to know about the surging coronavirus strain

The science is still emerging on the severity and impact of the variant.

With the CDC estimating that the delta variant accounts for more than 90% of new COVID cases in the U.S., scientists are still learning more about what makes this variant different from prior versions of the virus.

There are dozens of COVID-19 variants. Some emerge and quickly fade away. Others emerge and sweep the globe. The delta variant first emerged in India in December 2020 and quickly became the dominant strain there and then in the United Kingdom.

It was first detected in the United States in March 2021 and proved so dominant it supplanted the prior strain, called the alpha variant, within a few short weeks.

Now, experts say there's good news and bad news when it comes to this new variant.

Here's what we know now:

1. The delta variant is more contagious than earlier strains of COVID

Delta is more contagious because it “sheds more virus into the air, making it easier to reach other people," said Dr. Loren Miller, associate chief of infectious disease at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and Researcher at Lundquist Institute in Torrance, CA .

"There is also some evidence that the virus can more easily attach to human cells in the respiratory tract,” Miller said. This means that “smaller amounts of virus [particles] are needed to cause infection compared to the original strain.”

2. It could cause more serious illness in unvaccinated persons, but scientists don't know for sure.

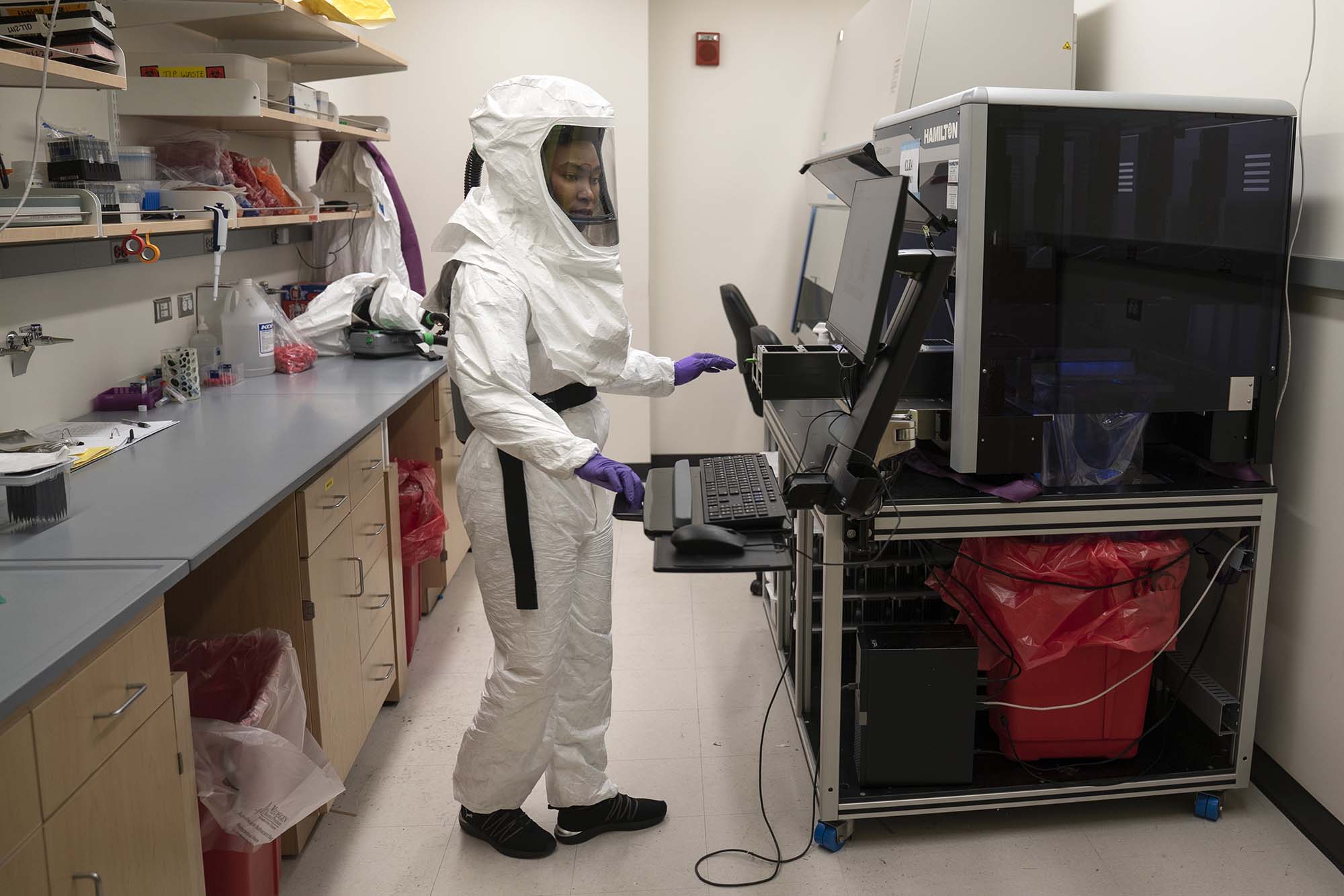

Scientists are racing to study the severity of the delta variant in real time. Until more studies are verified by a panel of scientific experts or gain “peer-approval," public health officials cannot definitively say for sure that it does cause more serious illness.

Here is what we know so far.

One peer-reviewed study in Scotland looked at over 19,000 confirmed COVID cases between April to June 2021. Scientists were able to differentiate between the delta variant and the alpha variant by molecular testing for one of multiple mutated genes known as the S gene.

About 7,800 COVID cases and 130 hospitalized patients had the delta strain confirmed by presence of the gene. Scientists noted that there was an increased risk for hospitalization in patients with delta when adjusting for common factors such as age, sex, underlying health conditions, and time of disease.

Another recent study awaiting peer approval in Singapore, noted that the delta variant was significantly associated with increased need for oxygenation, admission to an intensive care unit, and death when compared to the alpha variant.

Similarly, a Canadian study awaiting peer approval looked at over 200,000 confirmed COVID cases and found that the delta variant was more likely to cause hospitalization, ICU admission and death.

It’s hard to know whether delta is in fact making people sicker or if it is just affecting more vulnerable, unvaccinated populations with high case numbers and overburdened healthcare systems.

3. Delta is now the dominant variant in the US and around the globe.

COVID cases are skyrocketing again in the U.S., particularly where vaccination uptake has been particularly slow.

According to the CDC, more than 90% of COVID cases in the U.S. are currently caused by the delta variant. We know that “there is a lot of Delta out there … from the public health authorities who regularly survey for delta [and other strains] using special tests called molecular typing” said Miller.

4. COVID vaccines still work against the delta variant.

The “majority of currently hospitalized COVID patients are unvaccinated," said Dr. Abir “Abby” Hussein, clinical infectious disease assistant professor and associate medical director for infection prevention and control at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle, Wash.

Studies show that vaccines still dramatically reduce the risk of hospitalization and death, though the delta variant may be more likely than prior variants to cause asymptomatic or mild illness among vaccinated people.

Still, even amid the delta surge, this is still a “pandemic of the unvaccinated,” said Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky.

Although there are rare cases of severe breakthrough infections that require hospitalization that can occur in persons with a “weakened immune system," Miller said. This comes in time for the new guidelines for booster COVID shots in immunocompromised patients.

5. The delta variant surge is hitting younger, unvaccinated people harder

More COVID cases are being reported in teens, young and middle-age adults. That's not because delta is inherently more dangerous for younger people -- but rather, because younger people are less likely to be fully vaccinated.

Hussein explains that this is likely due to early vaccination efforts to vaccinate older high-risk people, particularly those who live in nursing homes. According to the CDC, more than 80% of adults over the age of 65 have been fully vaccinated and more than 90% of adults over 65 have had one dose (of a two-dose vaccine).

“Unfortunately, many younger adults have not been vaccinated, resulting in this shift to younger hospitalized patients," Hussein said.

Collectively, experts agree that the delta variant poses a new threat. Stopping transmission is the key to controlling all variants, not just delta. The best way for everyone to protect themselves against delta includes tools that are already at our disposal -- vaccination, masking, social distance and hand washing.

While we all want to return to a state of normal, Miller said “sticking to these basic messages is a very powerful way to prevent COVID transmission and protect yourself.”

Jess Dawson, M.D., a Masters of Public Health candidate at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, is a contributor to the ABC News Medical Unit.