What Life Is Like in Flint, Michigan, 3 Years Into the Water Crisis

Health officials say filtered water is safe to drink for most residents.

— -- For Jacob Uhrek and his five children, every sip of water, every boiled pot of noodles, every drop of water to brush his teeth comes from the same source as it has for the more than two years: bottled water.

"We bathe with filtered water," Uhrek, who lives in Flint, Michigan, told ABC News. "We still don’t drink or cook," non-bottled water.

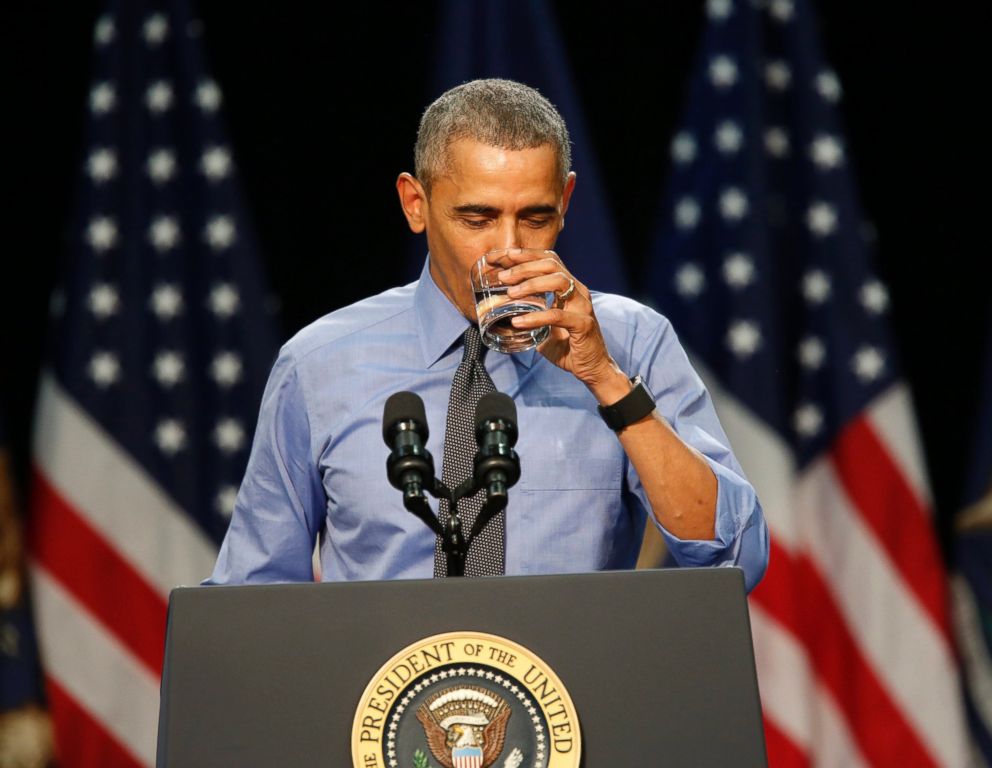

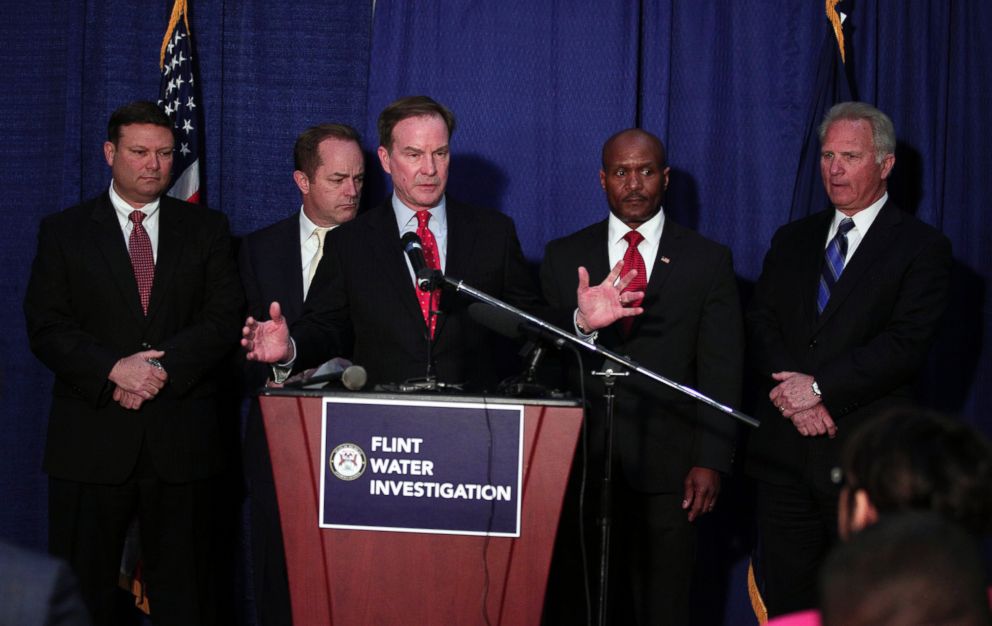

Flint has been in the headlines for months now after elevated lead levels were found in the municipal water system last year: President Obama visited the city earlier this month and drank the water to show that the water is safe to drink as long as residents use filters; celebrities held a fundraising concert on Oscar night; and three state officials are facing criminal charges over the water crisis.

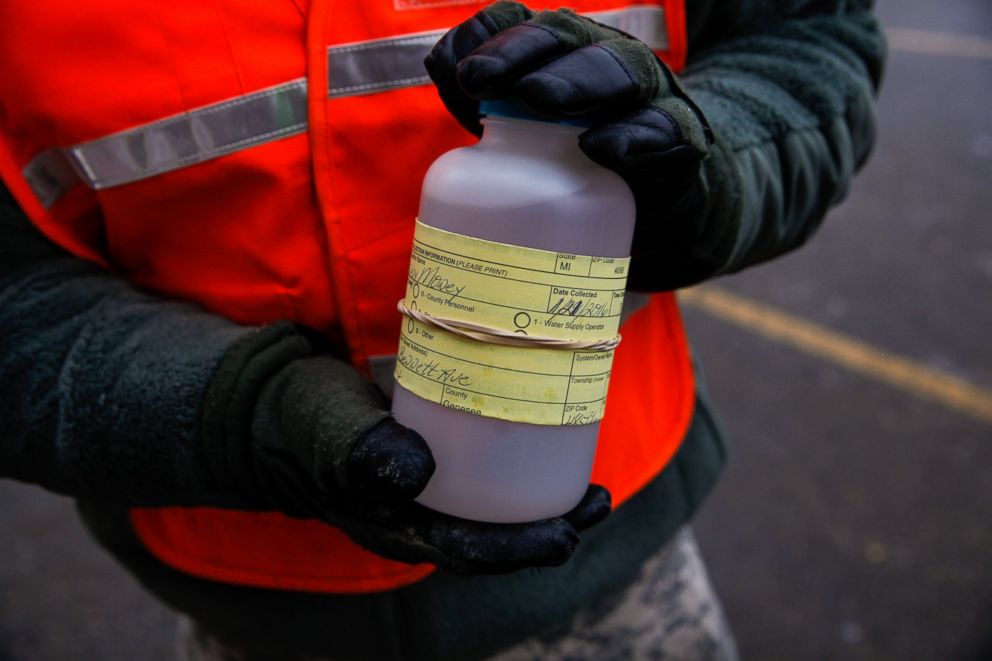

Elevated lead levels were found in the Flint water supply after the city disconnected from Detroit's water supply and began drawing its water from the Flint River in April 2014. It was intended as a stop-gap measure until the completion of a pipeline to Port Huron Lake as the source for Flint's municipal water.

Flint's Water Crisis Back in the National Spotlight

But it was later discovered that lead from the old pipes had begun to leach into the water due to improper treatment of the water from the Flint River. And even though the supply was switched back to the Detroit water supply in October, the anti-corrosive chemicals that were used to stop the leaching have not yet been able to bring down the lead levels in unfiltered water, according to state officials.

Lead is a known neurotoxin and is particularly harmful to young children whose neurological systems are still developing. Early lead exposure can have a lifetime of consequences, including lowered IQ, behavioral issues and developmental delays among others, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For residents dealing with the crisis day to day, life hasn't returned to normal. Uhrek said his family uses filtered water to bathe but for drinking and cooking, they're still using bottled water. Fortunately, none of his five children have tested positive for high lead levels, he said.

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services advised that residents could drink filtered water as long as they were over the age of 6 and not pregnant.

Uhrek said he's frustrated with what he feels has been a slow government response to the crisis, he also said he's been impressed by how local community members have come together, citing a nearby church that has kept up water donations after a local water supply station closed.

"The community is pulling together. We’re seeing actual change but it’s in the people," Uhrek said. "We’re going to make it through."

Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a local pediatrician, has been studying the lead levels in children in the community for years and helped draw attention to the crisis by publishing a paper finding children in Flint had significantly higher lead levels than their counterparts in surrounding areas after the water source was changed. Hanna-Attisha has been advocating for and talking about Flint for more than a year, but said the community still lacks long-term support.

"This is unlike any other disaster," Hanna-Attisha told ABC News. "The impact of [this] disaster will last for decades and maybe generations. We have yet to garner the long-term [financial] help."

One major difficulty will be trying to determine just how many children were exposed to elevated lead levels and who is most at risk, she said. Children are normally not tested for lead levels until they're a year old, however, a fetus can be exposed in utero or an infant during their first few months of life if their parents used tap water to give them formula.

Congress has yet to pass funding to help alleviate the water crisis in Flint or to help children who were exposed to high levels of lead. In the Senate, a bipartisan bill has been proposed that includes more than $200 million in federal funding to help children and others affected by the Flint water crisis, but currently there is no vote scheduled on the bill.

Hanna-Attisha said she's been frustrated to see funds that could help Flint languish in Congress.

"It’s not a political issue, this is a humanitarian issue," she said, noting that this "great American city" has had contaminated water for three years now.

Hanna-Attisha along with others at the Hurley Medical Center are working with Michigan State University and the Genesee County Health Department as part of the Pediatric Public Health Initiative started in January. The initiative has three goals -- to continue research on lead exposure in children in the area, to monitor these exposed children and get them assistance if they show developmental delays, and provide the tools and resources to monitor and help the children.

"I will keep talking and keep advocating. The story is not over," Hanna-Attisha said.

The city has hired 10 additional school nurses and the state has passed a Medicaid waiver that will add an additional 15,000 kids to Medicaid so they can get better treatment, she noted. Food and healthy eating has also become a focal point for health officials in the region, since an unhealthy diet low in iron means people can absorb more lead into their bones. There is also temporary funding for a new "nutrition prescription" program in which kids can redeem $10 vouchers for healthy foods at a nearby farmer's market, Hanna-Attisha said.

"There’s a lot more coordination of resources and programs," she said.

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder has outlined a plan to address the long-term damage that children exposed to lead could face, including new screening measures to help identify potential behavioral problems, expanding a free breakfast program, offering professional support and case management when children under 6 are found to have high lead levels, and addung more child and adolescent health centers in the county.

State and local health officials have now been joined by officials from the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention as well as the Federal Emergency Management Agency, as a state of emergency in the county has been extended into the summer.

Dr. Eden Wells, chief medical executive of the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, told ABC News that researchers are seeing progress in water quality. Recent water quality tests conducted by the CDC have shown filtered water may even be safe for pregnant women and young children, but Wells cautioned they're still awaiting final results and have yet to issue a new advisory.

"Even if there are high levels of lead, the filters seem to work," Wells said.

In addition, the Environmental Protection Agency has launched a campaign to get residents to flush out particles that may be lingering in the water system, Wells said.

The city faced another setback when a legionella outbreak was discovered in the area that sickened more than 90 people in 2014 and 2015. About half were linked to an area hospital, but health officials were also investigating whether the outbreak could have been related to the corroded pipes that leeched lead. Wells said this year the city is under enhanced surveillance for legionella so that officials can act quickly and identify the source of the outbreak. The last known case occurred in October 2015, but the disease is more common in summer months.

Marc Edwards, a professor of civil engineering at Virginia Tech and founder of the Flint Water Study, said he was more hopeful after seeing federal and state agencies working to fix the effects of the water crisis.

"I think that all parties at the table right now are really working at their best to get Flint back on its feet," Edwards said. "Since January, people have been trying their very best to help with the situation."

However, Edwards said after talking to residents, he thinks it will take a long time before they trust their government.

"For many in Flint, they will never drink water or take a bath or shower [in tap water] ever again," Edwards said. "The betrayal and loss of trust is so profound and it can never be restored."

He and his team are still in the area testing water and working with health officials to monitor the situation. Edwards said he's become concerned that some people have become so afraid of the water they have stopped bathing or washing their hands and that could lead to further health consequences.

"If people are fearful of bathing and washing hands, people will get hurt," he said.

For Jacob Uhrek, he said he's annoyed that he is again getting a water bill that had been temporarily suspended earlier this year and he's looking into getting a filter that will treat all the water in the house. This summer he plans on keeping his children away from pools.

"We got lot of freshwater and lakes," in Michigan, he said.

ABC News' Ben Siegel contributed to this report. Dr. Laura Johnson is a preventive medicine resident at the University of Michigan School of Public Health interning with the ABC News Medical Unit. She is also a board-certified physician in infectious diseases.