'Reparenting' Used to Treat Woman with Munchausen's Syndrome

Andrea Avigal hit rock bottom in 2005, lying in a hospital dying of sepsis.

March 5, 2014— -- Andrea Avigal hit rock bottom in 2005, lying in a hospital intensive care unit dying of sepsis. The former nurse and mother of two young daughters had intentionally injected herself with bacteria, subconsciously seeking attention.

Avigal, not her real name, had since childhood suffered from Munchausen's syndrome, a psychiatric disorder that is rarely curable, drinking poison, starving herself and taking excessive laxatives -- once 90 of them.

"At 5, I went into the bathroom and cut my finger with glass and showed my parents," she told ABCNews.com. "I thought it would stop the arguing and it didn't work, but I got the attention I wanted. Around 12 or 13, I faked having an asthma attack and went to the emergency room and tried to break a bone by hitting my wrist with a hammer, hard."

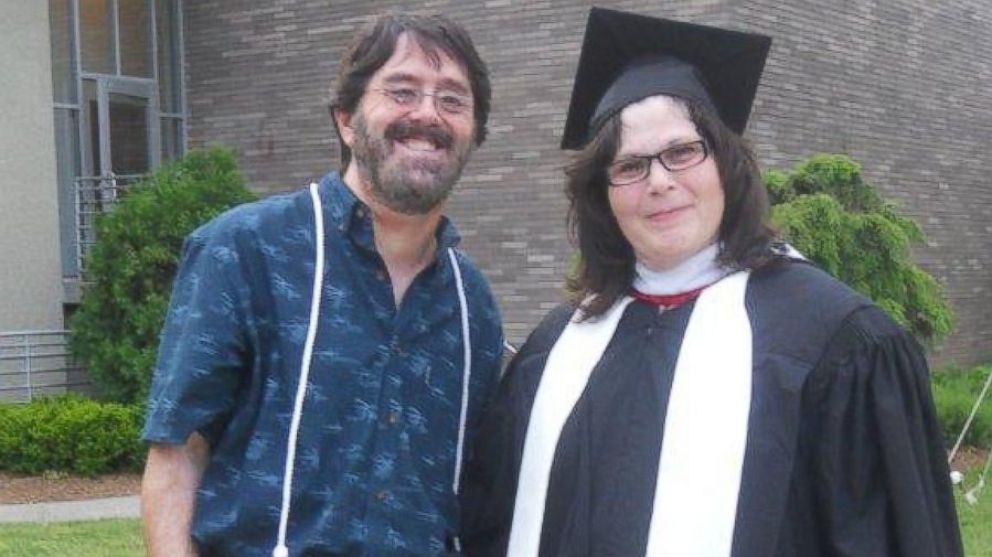

Avigal, now 53, says she has had a remarkable recovery with the help of New Palz, N.Y., psychologist Tom G. Hall, who used unconventional methods to teach her healthier ways of coping.

Together, they wrote about her struggle in the book, "Secrets Unraveled: Overcoming Munchausen Syndrome."

Today, the pair is committed to educating others about an unconventional treatment they call "reparenting" to bring hope to those who suffer one of the cruelest, and least curable, of psychiatric disorders.

Hall allowed Avigal to contact him by email and telephone at any time outside scheduled therapy sessions, becoming a surrogate parent. Hall is a pseudonym, because he is still treating other patients for whom he cannot offer counseling around the clock. However he revealed his real last name to ABCNews.com

"I saw that her healing depended more on our relationship itself than any insight I offered, and I felt compelled to expand my role beyond the bounds of conventional therapy," he writes in the book's introduction. "This choice stretched me as a psychologist and a person, pushing me well outside of my emotional comfort zone. In the end, it proved instrumental to Andrea's recovery."

Patients with Munchausen's syndrome have a subconscious need for attention and pretend to be sick or injure themselves on purpose. They invent symptoms, beg for risky operations and even rig lab tests to win sympathy and concern, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Many have worked in the medical field, where they may have access to syringes and medications.

"It's often found in people with a history of severe child abuse, which was the case with Andrea," Hall said. "It becomes an alternative way of getting attention in terrible situations and carries into adulthood almost like a pattern of addiction. Often people go for many years, from hospital to hospital, emergency room to emergency room, with medical professionals not aware they are creating their own illnesses."

Munchausen's syndrome differs from Munchausen by proxy, a form of child abuse in which a parent induces illness in a child. The syndrome falls under the category of factitious -- Latin for "artificial" or "contrived" -- disorders, which incur hospital costs in the tens of millions of dollars each year.

The American Psychiatric Association's new DMS-V estimates that 1 percent of all hospital visits are by patients with Munchausen's syndrome, according to Dr. Marc D. Feldman, a leading expert in factitious disorders and a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Alabama.