'They didn't run the plays': Ex-officials say Trump administration didn't use pandemic 'playbooks'

Trump criticized a "system we inherited," but ex-officials say plans existed.

President Donald Trump proclaimed in late March that “nobody knew there’d be a pandemic or an epidemic of this proportion.” Confronted with criticism of a lethargic national response, he lamented “a system we inherited” from past administrations.

The problem with both statements, according to former public health officials, is that prior administrations not only “knew there’d be a pandemic,” they planned for it – extensively.

They did so by crafting so-called “playbooks” and engaging in “table-top exercises” for hypothetical outbreaks – the results of which bore a striking resemblance to gaps that have emerged in the federal government’s response to COVID-19.

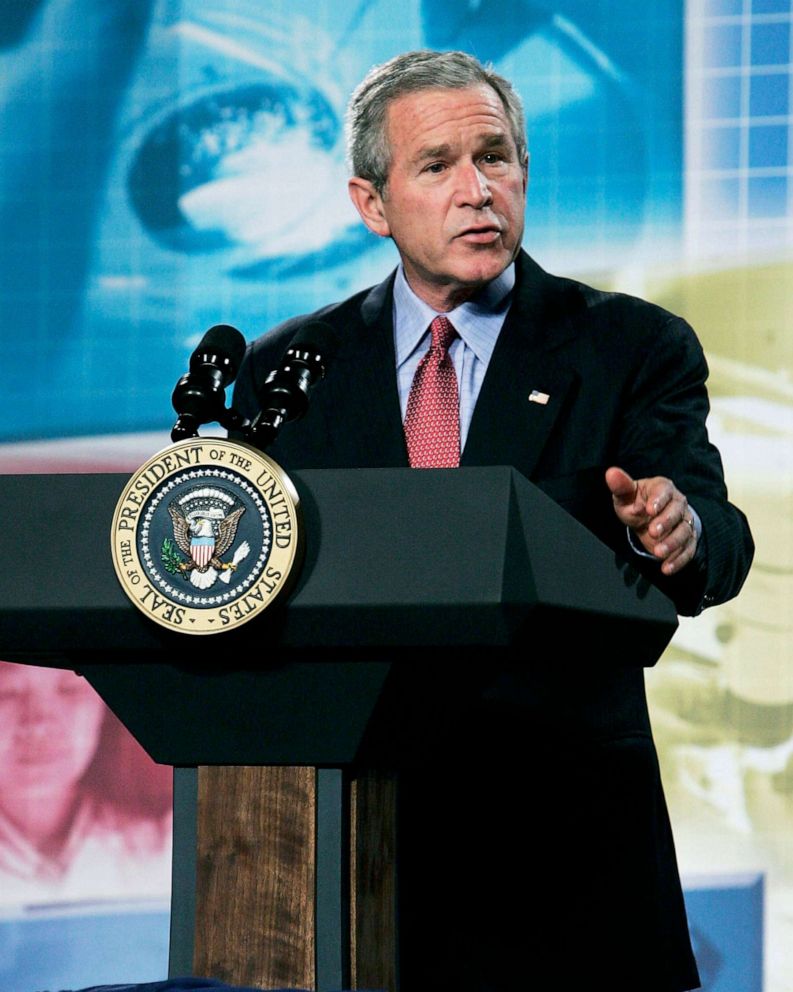

“I think that this current pandemic has really played out in many ways similar to exercises and table-top simulations that we had done many years ago,” said Dr. James Lawler, a former White House National Security Council (NSC) official during both the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations who worked specifically on pandemic preparedness.

“I think, unfortunately, things have played out somewhat predictably,” he added.

Multiple public health officials under Presidents Bush and Obama who spoke with ABC News as part of its coronavirus special, “American Catastrophe: How Did We Get Here?”, described the painstaking lengths to which previous administrations planned for viral infectious disease pandemics.

Many of those same officials condemned the Trump administration for failing to execute on the strategies gathered as a result of those efforts, such as taking early and aggressive science-based actions, clear communication to the public, and collaboration with international and state partners.

Others accused the president of exacerbating matters by shuttering a NSC office specifically tasked with pandemic response preparedness.

“A lot of what you see in the planning from the mid-2000s in my time in the White House under President Bush really applies to today – no question,” said Tom Bossert, a homeland security advisor to Bush at the time and later to Trump. Bossert, who left the Trump administration in April 2018, is now an ABC News contributor.

“Those strategies and those plans were comprehensive,” he added. “And they addressed a number of issues that we've now seen unfortunately coming to light.”

Ron Klain, the Obama White House’s Ebola response coordinator, put a finer point on criticism of Trump.

“They didn't run the plays,” Klain said. “And it would have made a big difference if they had.”

A senior Trump administration official pushed back on claims that the White House did not take advantage of past preparations, insisting that the playbooks were, in fact, consulted and that concepts from those documents were incorporated into the administration’s response. The official did not offer a specific example of one such concept when asked.

Elizabeth Neumann, who until April served as the assistant Homeland Security secretary for threat prevention and security policy, defended some of the Trump administration’s use of past pandemic planning, but criticized its slow start and execution.

“The [Trump] administration has done many of the things called for in those plans. It is, in my opinion, more of a question of timing and prioritization earlier in the process,” Neumann said. “There were some early-on good decisions, but there seems to have been just a slowness in getting to the point of actually turning on the engines.”

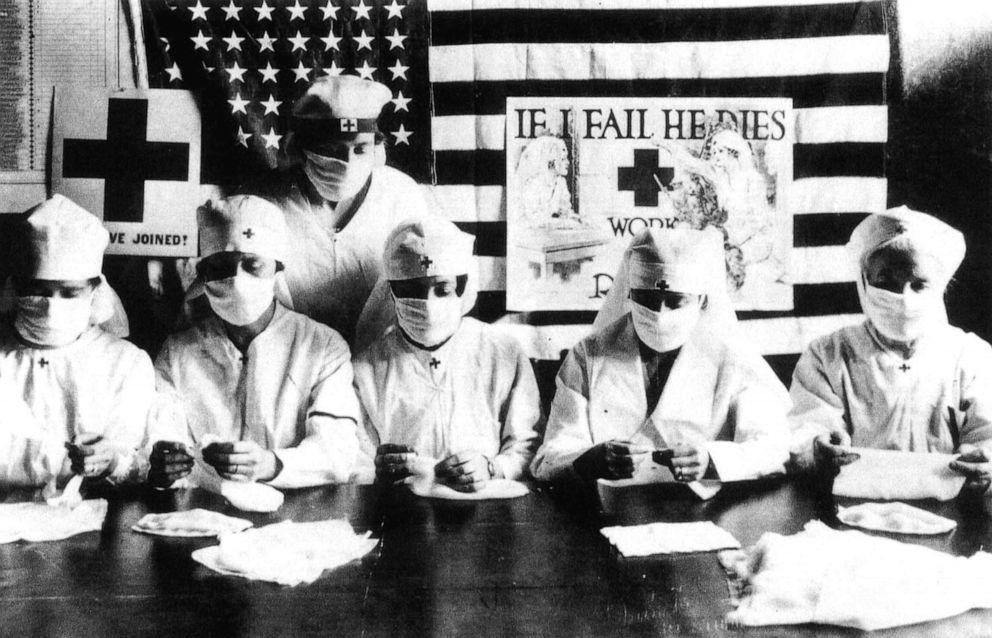

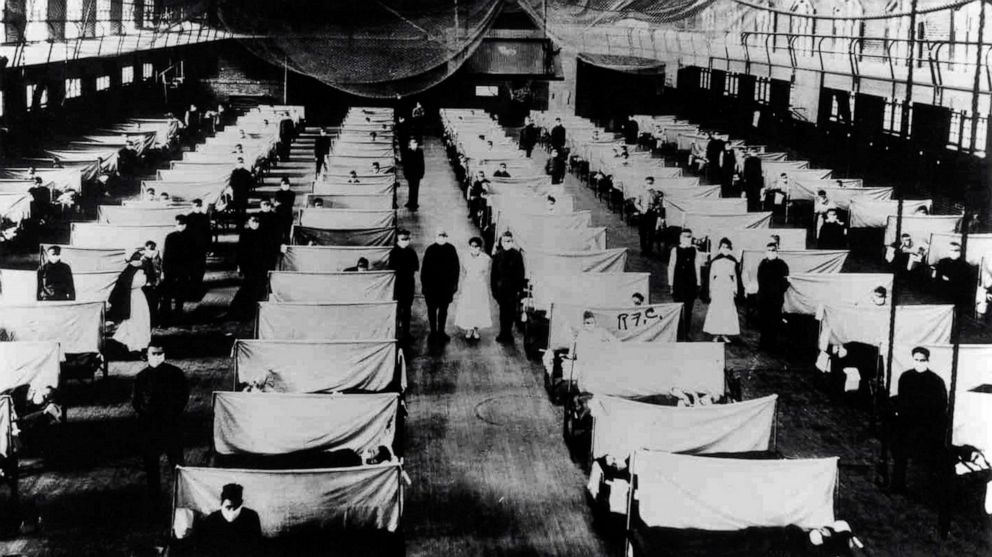

How a book on a century-old plague spurred US plans

Modern federal pandemic planning dates back to the summer of 2005, when then-President Bush tore through a book chronicling the deadly 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic while vacationing at his Texas ranch. He was riveted, and upon returning to Washington, Bush “asked his team to come up with plans for the nation to respond to a naturally occurring outbreak,” Bossert said.

“[Bush] was worried that we weren't prepared as a country to handle that, should it happen again,” Bossert added. “And, in fact, he was right.”

A pair of health scares around the same time compounded Bush’s fears. The U.S. largely managed to dodge a 2003 SARS virus that ravaged parts of Asia and Canada. In 2005, an avian flu that threatened Eastern Europe further rattled public health experts.

“The combination of those events and the growing recognition of the threat of pandemic diseases … really got us to our major efforts around pandemic preparedness in 2005, '06, '07 and '08,” said Lawler, the former Bush- and Obama-era NSC official.

Other Bush-era public health and national security officials speculated that the president’s experience handling the 9/11 terrorist attacks and Hurricane Katrina may have shaped his views on planning for the worst.

What emerged from the Bush administration’s efforts was a set of strategies for the federal government to quickly mobilize in the event of a global pandemic.

Dr. Julie Gerberding, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from 2002 to 2009, told ABC News that their plan emphasized the “importance of testing and diagnostics,” the need to “stockpile antivirals at the state and local level,” and “be able to provide … personal protective equipment.”

Bush never confronted a major outbreak. But in 2009, after Gerberding had left the CDC, a nascent Obama administration was confronted with its first public health emergency: the H1N1 swine flu pandemic.

“I watched from the outside with bated breath,” Gerberding recalled, “hoping that all of that planning and exercising would come to some good.”

It did. The CDC estimates up to 575,000 lives were lost to the swine flu worldwide. Of those, fewer than 13,000 were American, due in part to the Obama administration’s “complex, multi-faceted and long-term response,” the CDC later wrote.

The CDC cited a combination of robust contact tracing, bolstered state testing capabilities, and “quickly, proactively and transparently communicating accurate information to the public and to partners” as playing a role in the successful outcome.

Gerberding said “one of the most rewarding days” of her life after government was the day she was invited back to the CDC operations center as the swine flu receded.

“Everyone thanked me for really insisting that we pursue this level of preparedness,” she said. “But the team, in my opinion, in 2009, really demonstrated that the planning was worth it. Nothing is ever perfect. But I felt just so impressed and so proud of the job CDC did in 2009.”

After the swine flu subsided, the Obama administration built on the work of the Bush administration’s pandemic preparations.

Klain described the Obama administration’s “pandemic playbook” as “a step-by-step process for ramping up a response, for ramping up testing, tracing, all the things that were needed.”

“And on page nine of the pandemic playbook,” Klain added, “it said, ‘Hey, here's something to worry about: a coronavirus.’”

When Obama left office, a copy of it “was left for the Trump administration,” according to Klain.

“It said on the front ‘Pandemic Playbook,’” he said. “I don't know if the Trump administration didn't pay attention to the playbook, I don't know if they didn't read it, I don't know if they read it and ignored it.”

The White House NSC loses its pandemic office

The Trump administration has also drawn scrutiny for disbanding an Obama-era office within the NSC devoted to pandemic preparedness.

Klain said he encouraged Obama to activate this specified unit in the wake of the Ebola crisis “to get us ready for what was coming, and then to be in charge of the response when that threat eventually materialized.”

“When Trump came into office, he disbanded the single office on the [NSC] staff that was focused on biodefense and bio-preparedness,” said Dan Hanfling, a Virginia-based biosecurity and disaster response expert.

“In retrospect, not such a great move,” he added.

A senior administration official rejected claims that the office was dissolved or disbanded, telling ABC News that its work was absorbed by another office within the NSC because the two directorates shared “largely overlapping fields.” The official added that “no positions related to pandemic preparedness were eliminated” in the re-shuffling.

But Trump’s critics suggest his administration’s decision to disband the office reflected a broader skepticism of scientific evidence – and signaled that pandemic preparedness was not a priority.

Rep. Frank Pallone, D-N.J., who chairs the House panel with oversight of the federal government’s public health agencies, said the closure of the office amounted to an early warning sign that Trump would seek to “ignore and downplay the scientists and downplay the experts.”

“It was [later] compounded,” Pallone added, “by a purposeful effort on the part of the president to make it seem like the virus wasn't going to be as serious as it ended up being.”

Pallone pointed the finger at the president’s former national security advisor, John Bolton, whom he accused of “[getting] rid of the NSC team that was that put the playbook together.”

Bolton has also denied claims that he disbanded the pandemic team, insisting the office’s dissolution amounted to nothing more than a “streamlining” of the NSC.

“Global health remained a top NSC priority, and its expert team was critical to effectively handling the 2018-19 Africa Ebola crisis,” Bolton tweeted in March. “The angry Left just can't stop attacking, even in a crisis.”

Neumann, the former assistant homeland security secretary, said she understood Bolton’s intentions, but noted that the repercussions of his decision speak for themselves.

“It is my understanding that they were trying to reduce the size of the National Security Council, and there are a lot of arguments for why that is a good thing,” Neumann said.

“That said, the National Security Council plays a really critical role when it comes to crises and inter-agency coordination,” she continued. “In a case like a pandemic … it becomes a whole-of-government, even a whole-of-nation approach to responding to the disaster.”

Regardless of whether the pandemic planning office could have helped curb the disease’s spread, former officials dismissed Trump’s suggestion that “nobody knew there’d be a pandemic or an epidemic of this proportion.”

“Pandemics are not an unforeseen problem,” said Dr. Ali Khan, a former director of the CDC’s Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response. “We know they … have occurred throughout the history of mankind. So pandemics are absolutely not unforeseen problem.”

What to know about coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map