Vaccine nationalism: Experts warn countries against taking 'me-first' approach

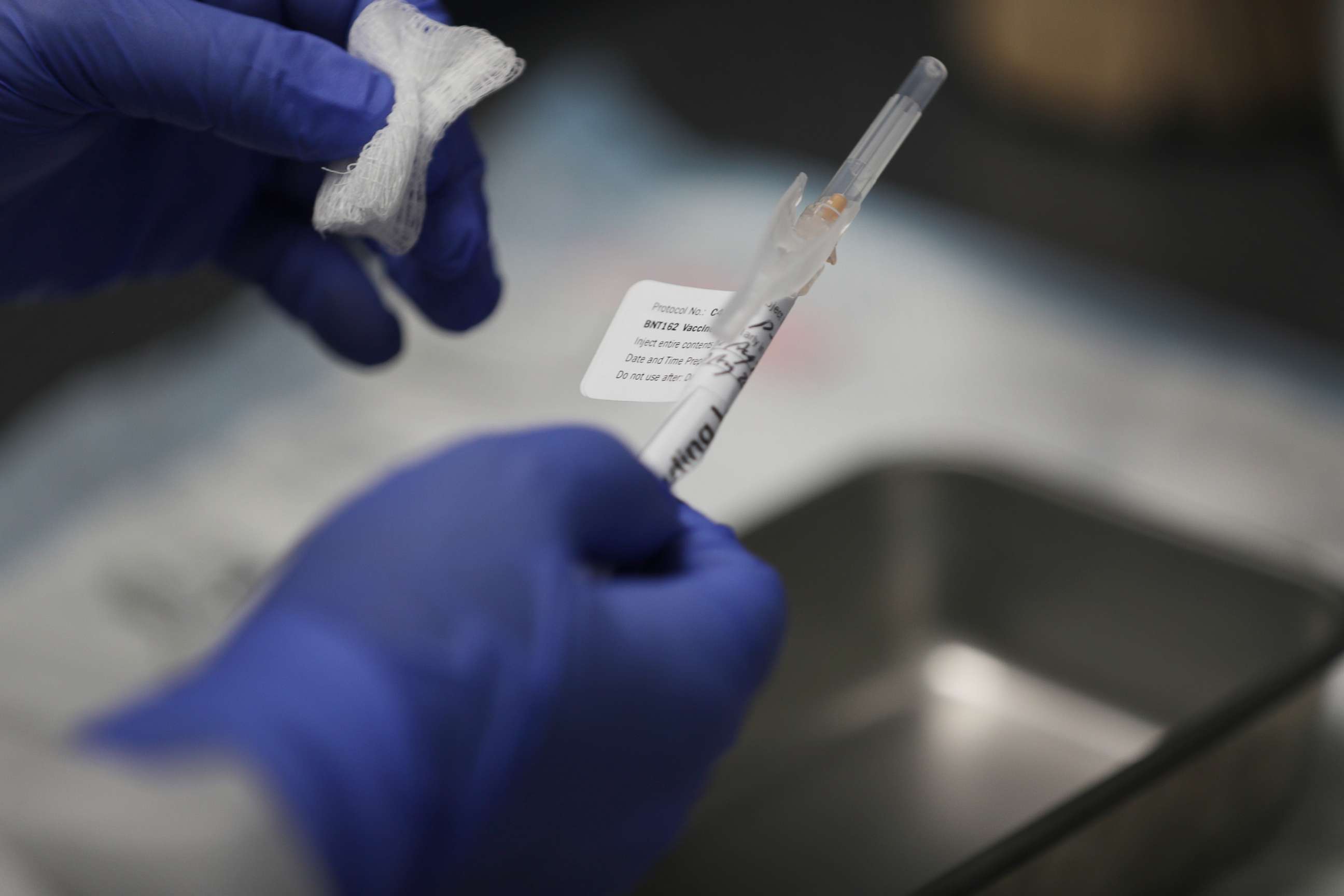

Wealthy countries are likely to get vaccine doses before less fortunate.

As the race for a novel coronavirus vaccine continues, there's growing concern from scientists and economic experts that wealthy nations are prioritizing getting doses for their own citizens at the cost of poorer nations and thus failing to control the global pandemic.

Some countries -- including the U.S. and the U.K. -- are securing vast quantities of new coronavirus vaccine candidates in a phenomenon being dubbed "vaccine nationalism."

Now, a growing chorus of experts is sounding the alarm. They say that with a virus capable of quickly spreading from country to country, vaccinating one nation at a time will ultimately prolong the pandemic, lead to more lives lost and continue to devastate the world economy.

"The virus does not know and does not respect borders. An outbreak of the virus anywhere threatens people everywhere," Dr. Dan Barouch, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, told ABC News.

While it's understandable for each country's "health departments to have a primary responsibly to their country's citizens," Barouch said, "each country needs to have a dual goal -- a goal of protecting their citizens and also ... to do their part in solving the global pandemic."

Economists Thomas J. Bollyky and Chad P. Bown have said the fastest way to stop the pandemic is by breaking chains of transmission by allocating the vaccine to people who are the most likely to be infected -- no matter where they live.

"Global cooperation on vaccine allocation would be the most efficient way to disrupt the spread of the virus. It would also spur economies, avoid supply chain disruptions, and prevent unnecessary geopolitical conflict," they wrote in a recent editorial published in Foreign Affairs.

Yet, even if global cooperation is the most efficient way to halt a virus in its tracks, it's a difficult political proposition.

In the midst of this debate, wealthy countries have invested heavily in ensuring that their own citizens get the vaccine first.

"Prioritization of vaccine access can't be governed by political borders. This means health workers and the vulnerable deserve to be first in line regardless of nationality," said Dr. John Brownstein, an epidemiologist and ABC News contributor.

The U.S. has Operation Warp Speed -- a government-funded initiative to turbocharge vaccine development and secure vaccine doses for the U.S. population. In total, almost $10 billion has been allocated by Congress for hundreds of millions of doses to be made available to U.S. citizens.

In Europe, there is the Inclusive Vaccines Alliance which has already agreed to buy 400 million doses of AstraZeneca's vaccine being co-developed with Oxford University.

The U.K. has made a deal with AstraZeneca and Wockhardt to secure and distribute 30 million vaccine doses by September, part of a broader push to get 100 million doses by the end of the year. A deal has also been made for the Sanofi/GlaxoSmithKline vaccine.

Some have compared the coronavirus vaccine buyouts to the 2009 swine flu pandemic, when wealthier countries bought up of most of the vaccine doses. The U.S. and many European countries donated some of their vaccines to poorer countries, but only when they were satisfied that they had enough doses for their own citizens.

That's important, because a strategy of vaccinating high-risk people first -- wherever they are -- is thought to be most effective at slowing viral transmission.

"Ensuring fair, equitable and transparent allocation is not just the right thing to do, it's in everyone's best interest," Brownstein said. "Placing certain wealthy countries at the top of this list will only serve to prolong the pandemic."

There are also implications for vaccine cost. Countries "bidding" against each other could also increase the cost of vaccines for everyone.

Even countries that do secure large doses of vaccine candidates, the risk remains that the vaccine they bought simply doesn't work well enough. Some countries could be playing a potentially dangerous game by gambling on a small number of vaccines.

Although the World Health Organization has set up a group called the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access, with a mission statement to guarantee "fair and equitable access for every country in the world," its lofty goals will only be realized with a formal and tangible commitment by powerful nations.

But like other global scourges, the burden of supplying a coronavirus vaccine to low-income countries is likely to fall to nongovernmental organizations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and international vaccine collaborations it founded, such as the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations and Gavi.

According to Barouch, nothing short of a global strategy will work to control the virus. "For a global pandemic, if the virus is not brought under control globally ... we will not solve the problem."

Dr. Laith Alexander is an academic doctor at St. Thomas' Hospital in London and working with ABC News' Medical Unit. Sony Salzman is the unit's coordinating producer.