Widowed father works with congresswoman on legislation to prevent maternal deaths

President Donald Trump signed the bill into law in December.

Sitting in the hospital room, mother and newborn baby were sound asleep.

"I was overjoyed. I remember thinking my family is complete," Charles Johnson told ABC News.

But then he looked down and saw his wife Kira’s catheter turn pink and then red with blood.

April 12, 2016 was supposed to be a joyous day for the Johnson family, but it turned into a "nightmare."

Ten hours later, Kira Johnson died as a result of internal bleeding following a cesarean section.

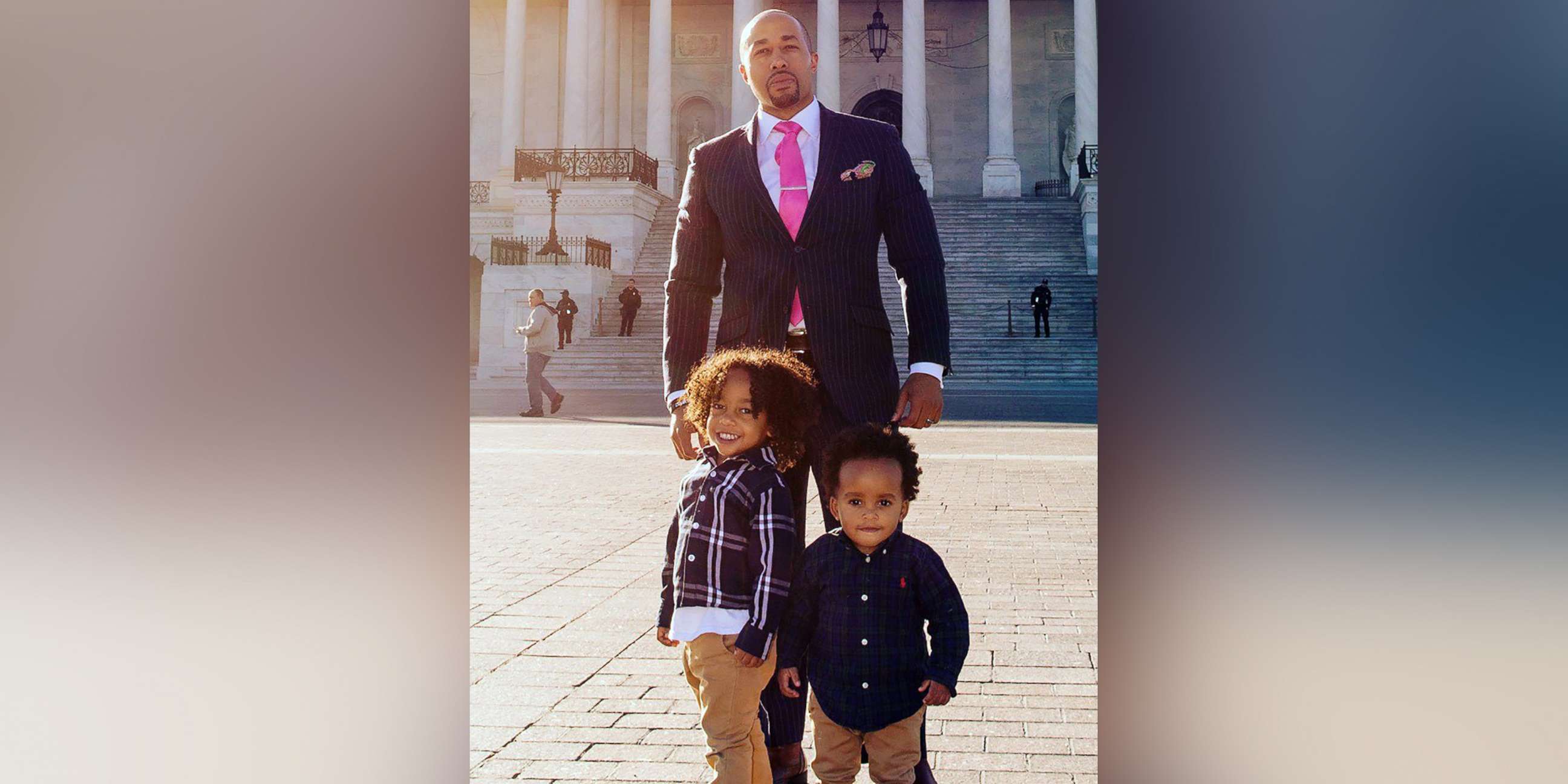

Now, two years later, Johnson is raising two children on his own and advocating to rectify the country's maternal health policies and regulations to prevent anyone else from sharing the same tragedy. Johnson took to Capitol Hill to share his wife's story before members of Congress, working alongside a congresswoman who experienced her own personal difficulties during pregnancy.

Charles and Kira Johnson welcomed their first son Charles V. in 2014. He was delivered via C-section. Two years later, the Johnson family relocated from Atlanta to Los Angeles and learned they were expecting their second baby boy.

"Kira and I had always wanted two boys," Johnson said. "I was excited."

The Johnsons decided to have Langston delivered at Cedars Sinai medical center, a non-profit hospital that is currently ranked as the eighth best hospital in the country by U.S. News and World Report.

Charles Johnson said his wife was in exceptional health and that she took all the necessary prenatal measures to ensure their second child would be born healthy. Since their first son was born via C-section, the doctor suggested the same for their second.

The Johnsons arrived at Cedars Sinai at 2 p.m. that day for Kira’s scheduled surgery. The C-section was a success and Langston was born without incident.

As his sleeping wife's catheter, which is a tube inserted in the bladder to drain urine, began to fill with blood, he alerted the nurses. It was 5:34 p.m. and a resident physician was called by a nurse, according to Johnson and medical records released by Cedars Sinai. At 6:44 p.m., a CT scan was ordered for a "surgical emergency."

Four hours later, the CT scan still had not been completed. Doctors had performed ultrasounds which showed her hematoma had enlarged, according to medical records.

Doctors came into the room and left, but Johnson said he doesn't remember them doing anything to help his wife. He said she was in more pain than she exhibited.

"Kira was such a strong woman, she always tried to put on a brave face," Johnson said.

About ten hours after reporting the blood in her catheter, Kira was taken to a procedure room. Johnson was told his wife would be back in 15 minutes.

"Baby I’m scared," Kira said holding her husband's hand.

He sat waiting in an isolated waiting room, listening to a vacuum roar as a custodian worked nearby.

After waiting patiently for 15 minutes, two residents walked into the room.

"Mr. Charles we need you to have a seat," Johnson recalled one of them saying.

There had been heavy internal bleeding, she flatlined and her situation was critical.

The residents informed Johnson they found 3 1/2 liters of blood in Kira's abdomen.

"But we're continuing to work on her," he was told.

He urged them to save his wife. Before he'd fully processed the dire situation, a doctor he'd never met before came out to tell him his wife had died.

Kira Johnson's death is not unique.

Pregnancy-related deaths have increased from 7.2 per 100,000 live births in 1987 to 18 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2014, according to research cited in H.R. 1318. The United States is ranked 50th globally for its maternal mortality rate and is one of eight countries in which the mortality rate has increased.

Research in the bill also states that women of color, in particular, are at a higher risk than others of dying from pregnancy complications.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention cites an abnormally significant ratio difference in pregnancy-related mortality rates by race. Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related issues than white women. During 2011-2014, the CDC reported "considerably racial disparities in pregnancy-related mortality exist" in its findings of 12.4 deaths per 100,000 live births for white women compared to the 40 deaths per 100,000 live births for black women.

Separately, the Brookings Institution conducted a study showing the most prevalent racial disparities within America's middle class and determined that black mothers with advanced professional degrees, such as a master's degree or higher, have a higher chance of infant mortality compared to white women whose highest education level is the 8th grade.

The causes of the gap remains unclear, but the National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine found it may be due to the way healthcare systems are organized and operated. Healthcare providers' biases, prejudices and uncertainty when treating minorities could also contribute to healthcare disparities. The study also claims patients' attitudes and behaviors play a role. A small percentage of minority patients do not trust health care professionals, according to NASEM.

U.S. Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler, R-Washington, who experienced pregnancy complications of her own, sponsored H.R. 1318, the Preventing Maternal Death Act of 2018.

In 2012, Herrera Beutler and her husband discovered they were expecting their first child -- only to be told their unborn child had Potter Syndrome, a rare disease that occurs when there is a critical lack of amniotic fluid surrounding a baby while in the uterus. It prevents the baby's kidney development, according to the National Institutes of Health.

They were told by doctors the disease was 100 percent fatal, but despite the prognosis, Herrera Beutler underwent an experimental treatment in which saline was injected to replace the amniotic fluid and help develop their unborn child's lungs.

"As she dug more into the issue, she was saddened to learn that this crisis impacts women of color and women in rural areas even more acutely, and she redoubled her effort to get this across the finish line," Herrera Beutler’s communication director Angeline Riesterer told ABC News in a statement.

The bill requires the Department of Health and Human Services to provide grants to all 50 states to establish state-based maternal mortality review committees to determine why women are dying from pregnancy-related deaths. The bill also ensures that the state department of health develops a plan for ongoing health care provider education in order to improve the quality of maternal care, disseminate findings and provide disclosure information in state reports for the public.

Johnson, who created 4Kira4Moms, in honor of his wife and to advocate for improved maternal health policies and regulations, has worked with Herrera Beutler on the issue.

"When I spoke about Kira’s story in front of Congress members, multiple members of Congress on both sides of the aisle were in tears," Johnson said. "Some members who weren’t even able to meet with me in times past, signed onto the bill a week later after my testimony."

The bill became law in December when the president signed it.

"Myself, an African American male from the deep South came together with a white Republican woman from Washington," Johnson said. "We worked together to make this what it truly is -- a human rights issue.

"This affects all women. I was proud the congresswoman stood shoulder to shoulder with me without backing away from acknowledging racial disparities within these stats. The fact we do come from such different worlds makes it all the better. This is a true bipartisan effort."

Johnson credited his wife as his motivation to move forward with his life, raising their two sons. He said she was an independent woman with "contagious energy."

"I made eye contact with this beautiful woman who was standing by the front door with her arms folded," Johnson said remembering when they first met at a party in 2005. "Frankie Beverly's 'Before I Let you go' played in the background. As I was leaving the party, I stepped out of my comfort zone and sang to her, 'Before I let you go, oh, I would never, never, never...'"

Kira, who had looked exasperated, couldn't help but smile. From there, they developed a close friendship and eventually a romantic relationship. They married in 2012.

Johnson said she was someone who "challenged him in every aspect of his life." After she died, that didn't change. He was inspired to try to prevent other families from experiencing the same tragedy.

"I thought I had a big heart until I met her -- she was just different," Johnson said. "She made my life full and complete."