Chernobyl 30 Years Later: Those Who Live in Its Shadow Still Suffer

Residents say their plight is being ignored by Ukraine's government.

IVANKOV, Ukraine -- In the days before the 30th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster today, workers hurriedly filled in pot holes and painted lines on the decrepit road to the destroyed nuclear station. They were getting ready for a visit by Ukraine’s president and memorial ceremonies at the site to mark the catastrophic incident on April 26, 1986.

Time has helped bury some of the most obvious effects of the catastrophe. Slowly the forest is breaking up the abandoned towns inside the exclusion zone; the famous “Red Forest,” of irradiated trees turned red by the reactor leak, has been cut down and replanted.

Radiation levels on the surface are often close to background norms, though highly contaminated patches still lurk everywhere. Next year, a giant new containment shell is due to be slid over the shattered reactor, sealing it safe for 100 years.

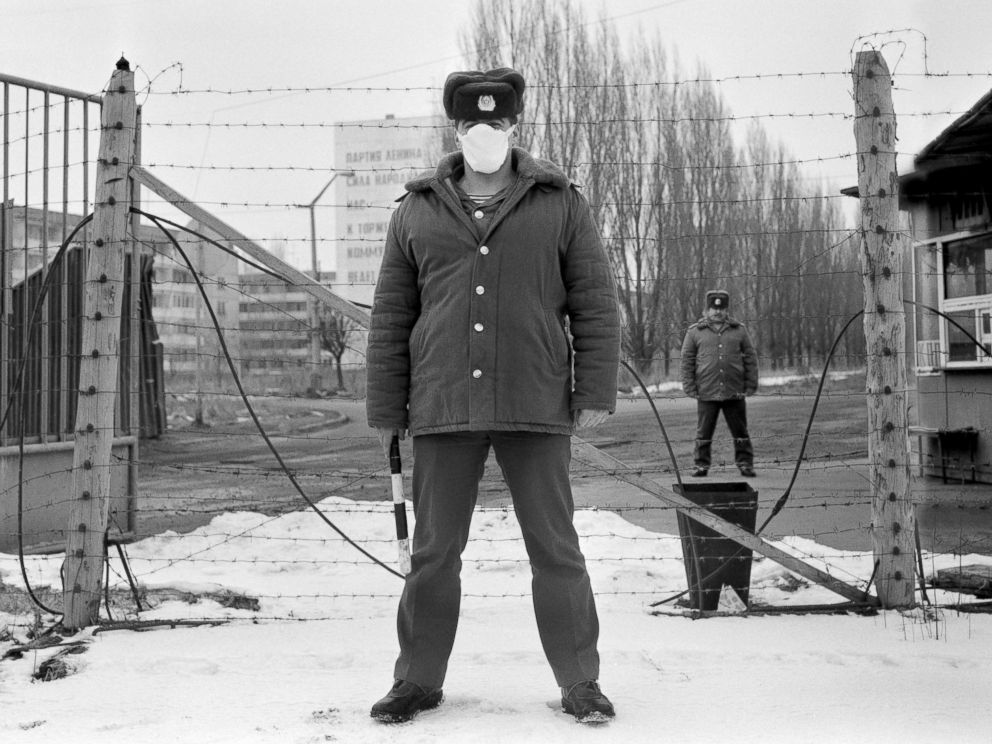

Haunting Images From Chernobyl

But as the workers spruced up the route to the world’s worst nuclear disaster zone, some affected by the accident said with the passing of time their plights were increasingly being downplayed and accused Ukraine’s government of trying to save money by cutting support to them.

The claims throw attention onto the fact that even 30 years on, the long-term health effects of Chernobyl remain intensely disputed.

The disaster, the worst nuclear accident in history, eventually affected 3 million people and forced the evacuation of over 300,000. The reactor was sealed inside an 18-mile exclusion zone, deemed too contaminated for people to live and known now just as the Zone.

The United Nations and the World Health Organization have found that other than the tens of thousands exposed immediately after the accident, there is no evidence to show Chernobyl’s leaked radiation has had a major impact on public health. The International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA) has said radiation levels have fallen by a factor of several hundred and that most contaminated land has been made safe.

But some local doctors and researchers reject this, saying they have documented a growing number of long-term health issues among people living in areas close to the exclusion zone, particularly among children and arguing that even small doses of radiation over long periods is dangerous.

“The level of illness is much higher than in the regions that are not contaminated,” Oksana Kadun, head doctor at Ivankov hospital, the closest to the Zone. Kadun, who is helping with a European Union-funded study tracking the health of 4,000 children in contaminated areas, said she saw increased cases of respiratory problems and immune system deficiency.

With the contaminated regions poor and of little influence, there was little appetite to reopen the issue, Kadun said.

“Few people are talking about this because nobody wants to hear it,” she said.

In the villages of ginger-bread cottages strung along the plain just outside the Zone, where storks build their nests on pylon-tops and people work tiny plots of land by hand, many assume they are poisoned but say they have little way to prove it. Too poor to buy food, most grow their own and forage from ground they know is contaminated.

“What we have, we use,” said Anna Pogorelova, who lives with her two children in what was called the "Fourth Zone" -- an area once considered contaminated but not enough for evacuation.

In many places here, Ukraine’s government pays people compensation for Chernobyl—known by Ukrainians as “coffin money”. But with the country on the edge of default, the government has been curtailing the payments for some and reclassifying areas previously deemed contaminated.

Officials have said they are making tough choices with limited resources, but those affected by the accident say the government is trying to ignore legitimate cases.

“We have the impression that they would rather that we had just gone already,” said Nadezhda Makarevich. Makarevich was evacuated from Pripyat, the town closest to the reactor. On the morning after the explosion, she was washing her windows. Not alerted by the Soviet authorities, she inhaled fallout, suffering radioactive burns on her lungs.

Makarevich is part of a group campaigning for the government to pay support benefits to those poisoned by the accident, as it is obliged by law.

With so many once classified as victims of Chernobyl -- the number of so-called “liquidators,” workers who contained the accident, is around 500,000 -- and the illnesses so long-term, those claiming Chernobyl benefits are often stigmatized as scroungers.

In the villages around the Zone, many say they’re resigned to living on contaminated ground. In any case, they say, radiation is only one of their problems.

“We’re not a big region,” Pogorelova said. “No one pays us any attention.”