Amid boycotts, US scrambling to make Summit of the Americas a success

President Joe Biden is hosting the summit starting June 8 in Los Angeles.

MEXICO CITY -- The week-long Summit of the Americas, slated to start June 8 in Los Angeles, is a big deal for the Western Hemisphere -- bringing together leaders from North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean.

But President Joe Biden's opportunity to host the high-profile gathering is running into some major problems that threaten to undermine the meetings -- and Biden's push to reassert U.S. leadership in the region.

Several leaders are threatening to boycott the summit because the U.S. has decided to not invite the governments of Venezuela and Nicaragua. And without these leaders' participation, agenda items like a region-wide agreement on migration and efforts to combat climate change and the economic and social impacts of COVID-19 are in doubt.

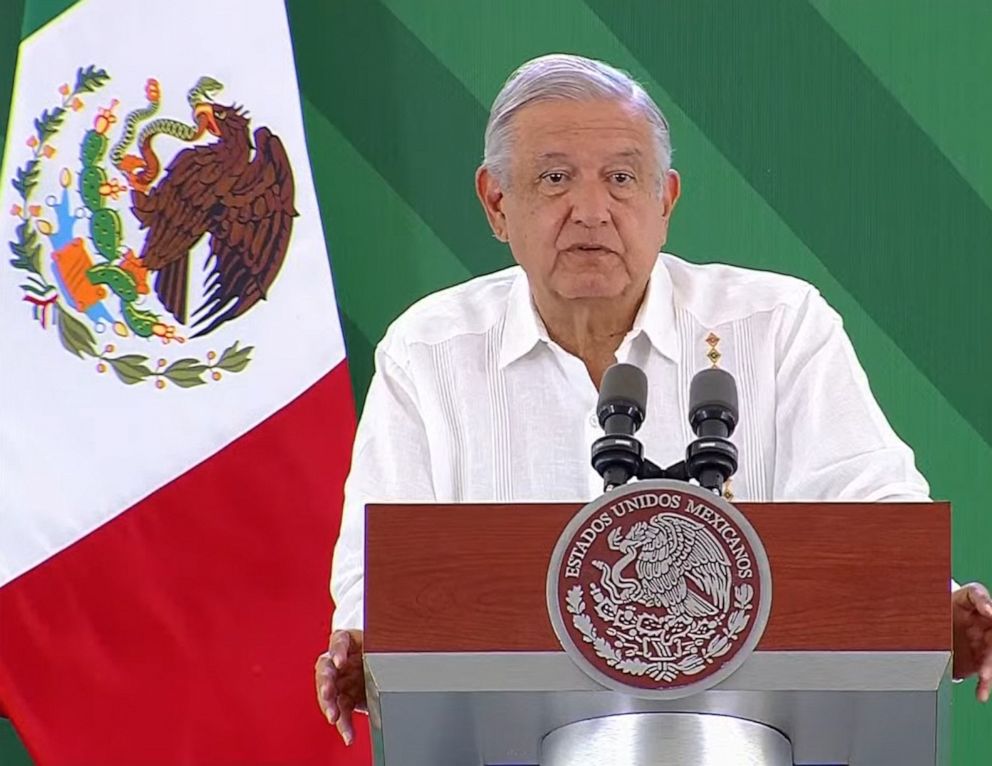

"If all of the countries are not invited, I am not going to attend," Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador reiterated Friday. He's repeatedly said all of the region's countries must be invited, including those that Washington considers authoritarian and are under U.S. sanctions -- Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua.

Criticism like that has had the Biden administration scrambling to shore up attendance, including by dispatching Vice President Kamala Harris, first lady Dr. Jill Biden, and a special adviser for the summit, former Democratic senator Chris Dodd.

"Is it going to be the Summit of the Americas or the Summit of the Friends of America? Because if those countries are excluded, what continent are they from? Are they not from the Americas?" López Obrador, known by his initials as AMLO, added during a press conference Friday.

Losing the leader of Mexico, the 15th largest economy in the world and one of the region's most important players, would be a big blow. U.S. officials, including Dodd, Biden's friend and former Senate colleague, have been talking to AMLO's government to secure his attendance.

But AMLO is not alone. The leaders of Bolivia, Antigua and Barbuda, and Guatemala have announced they will not attend. And others, including in Chile and Argentina, have criticized the snubs.

Even Honduras, whose left-leaning female president -- the first in the nation's history -- has been showered with attention by the Biden administration, has threatened to not attend.

"I will attend the summit only if all of the countries in the Americas are invited without exception," President Xiomara Castro tweeted Saturday.

That line in the sand was drawn just hours after Castro spoke with Vice President Harris. Harris, who Biden tapped to oversee the administration's efforts to address migration from Central America, has sought to secure an ally in Castro -- attending her inauguration in January and becoming the first foreign leader Castro met with after taking office.

While the U.S. readout of their Friday call made no mention of the summit, that Castro voiced clear opposition so shortly after is another troubling sign for the administration.

"Whether or not a widespread boycott of the summit ultimately materializes, the stresses in U.S-regional relations will have been exposed in an unflattering light," Michael McKinley, who served as U.S. ambassador to Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, wrote in an opinion piece for the U.S. Institute of Peace.

"The uncertainties surrounding the summit," he added, "are a wake-up call for the United States."

Salvaging attendance could be one reason for those recent reversals in U.S. policy toward Cuba and Venezuela. Biden administration officials have denied that was the case, but a senior Caribbean-nation official said they made a difference in getting 13 of the 14 island nations to RSVP yes, according to Reuters. On Friday, the U.S. Treasury extended the oil company Chevron's license to keep operating in Venezuela, stopping short of allowing the resumption of oil exports, but another good will gesture to Nicolás Maduro's government.

But the U.S. made clear Thursday -- it is not inviting the governments of Venezuela or Nicaragua, per Kevin O'Reilly, the top U.S. diplomat coordinating the summit. O'Reilly said the U.S. still doesn't recognize Maduro's legitimacy, but deferred to the White House on whether the U.S. would invite opposition leader Juan Guaidó, who the U.S. recognizes as Venezuela's "interim president."

While those exclusions were confirmed, whether Dodd and others can convince AMLO to come anyway is still an open question. The Mexican populist president, who's said he may send his Foreign Secretary Marcelo Ebrard in his place, left the door open -- praising Biden as a "good person, he doesn't have a hardened heart."

But Dodd's efforts appear to have paid off elsewhere -- after meeting Dodd on Tuesday, the far-right president of Brazil, another of the region's major powers, is attending, per Brazilian newspaper O Globo. It will be the first time Biden even speaks to Jair Bolsonaro, whose attacks on the environment and Brazil's democratic institutions -- and his close ties to Donald Trump -- have cooled relations with the White House.

In addition to Dodd, the administration deployed first lady Jill Biden on a six-day goodwill tour through the region this month. Biden, who will attend the summit with the president, visited Ecuador, Costa Rica and Panama -- and batted away concerns about a boycott in between stops promoting U.S. investment and assistance in each country.

"I'm not worried. I think that they'll come," she told reporters as she departed San Jose, Costa Rica, on May 23.

O'Reilly told the Senate Thursday that the White House has not made a decision yet about inviting Cuba -- a week and a half after the administration reversed Trump's hardline policies. The White House announced flights to cities beyond Havana will resume, people-to-people exchanges will be permitted, and remittances will no longer be capped, among other steps that moved toward, but fell short of the rapprochement under Biden's old boss, Barack Obama.

But regardless of a U.S. invite, Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel announced Wednesday that "under no circumstances" will he attend, accusing the U.S. of "intensive efforts and ... brutal pressures to demobilize the just and firm claims of the majority of the countries of the region demanding that the Summit should be inclusive."

The invitation list is also drawing criticism from Biden's own party. Fifteen House Democrats, led by House Foreign Affairs Committee chair Gregory Meeks, wrote to Biden Thursday expressing "concern" about the decision.

"We feel strongly that excluding countries could jeopardize future relations throughout the region and put some of the ambitious policy proposals your administration launched under Build Back Better World at risk," they wrote in their letter.

Others on Capitol Hill have argued in the opposite direction-- with Sen. Marco Rubio, the top Republican on the Senate's subcommittee for the Western Hemisphere, saying Thursday that the U.S. should not be "bullied" by AMLO or others and should not invite dictators.