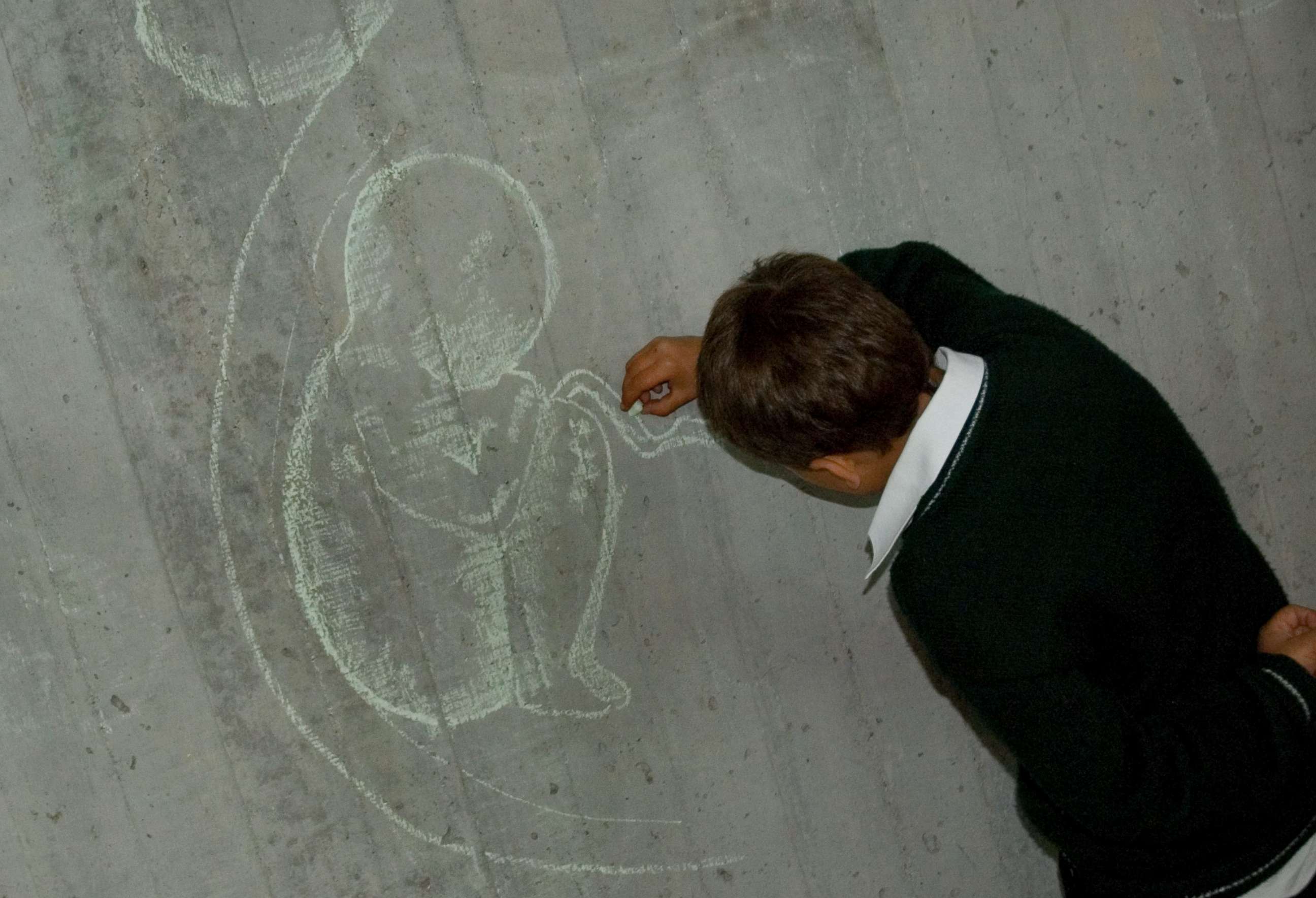

Colombia to decide on historic abortion ruling

The current ruling in the country allows for abortion in only three instances.

Fourteen years after Colombia's landmark decision to legalize abortions in some cases, the country is once more bracing itself for a historic vote.

The Colombian Constitutional Court has until Feb. 19th to decide whether it will legalize abortion for pregnancies up to 12 weeks. The current law allows for abortion in only three instances: if the mother's life is at risk, if a fetus is malformed or if the pregnancy is a result of rape.

This is the "first real opportunity to actually advance reproductive rights," according to Paula Avila-Guillen, the director of Latin America Initiatives for the Women's Equality Center.

"I think they have the opportunity to actually make history," Avila-Guillen told ABC News.

The decision is hanging on two female justices who have not yet made clear how they will vote, according to Avila-Guillen. She said that out of the nine justices, four men are in favor, and two men, as well as one woman, are against.

The country's current abortion law is among the more lenient in Latin America.

The Center for Reproductive Rights classifies Colombia's abortion law as legal if it is "to preserve health." Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador and Peru also fall under that category.

Six Latin American countries have total abortion bans: the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua and Suriname.

By law, all institutions providing health services in Colombia -- whether public, private, secular or religious -- are required to perform an abortion if a woman proves that she meets one of the three exceptions.

Even so, advocates say the reality is that it's not regulated and hospitals often deny women the service.

Out of the estimated 400,400 abortions performed in the country each year, only 322 are legal procedures performed in health facilities, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research organization on sexual and reproductive rights.

Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), or Doctors Without Borders, found that of the 428 women and girls who requested an abortion through MSF in 2017 and 2018, 88% reported that they faced at least one obstacle while trying to access the service.

MSF noted that while the data does not represent the country as a whole, "it does provide a snapshot of the situation."

There are two main abortion providing groups in Colombia: Orientame and ProFamilia, both of which have multiple facilities across the country.

Dr. Juan Vargas, a gynecologist of 25 years at ProFamilia, told ABC News that in 2019 the clinic performed some 22,000 abortions. He said that most of the women who seek abortion from a ProFamilia clinic do so for health reasons. Rape accounts for 1%, while fetal malformation makes up about 3%, according to Vargas.

He noted that rape survivors need to prove in some way they have been raped. It is most often done through a police report or complaint, he said; however, many victims of rape often do not report their assault.

Vargas said between 90 to 95% of women who seek an abortion are granted one at ProFamilia. Abortions that are not performed at one of the facilities are done in hospitals, where proper access is a major issue, according to Avila-Guillen.

"Safe abortions continue to be a problem," she said. "Access has never really materialized."

Unsafe abortions are one of the five leading causes of maternal mortality worldwide, according to MSF. The other four are postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis, birth complications and hypertensive disorders.

"Of all these, unsafe abortion is the only one that is completely avoidable," MSF reports.

Avila-Guillen said such a consequence makes the upcoming vote all the more important.

"This will be significant and a huge legacy for this court and these two women judges, which it's in their hands to recognize women's rights and women's autonomy and women's equality," she said.

Though Avila-Guillen did not have statistics on how the public in Colombia feels about abortion, she said like many places around the world, the country is in the midst of a "battle."

"We just elected our first female mayor who is married to a congresswoman, and I think that just shows you how Colombia is moving toward a more progressive society," Avila-Guillen said.

Yet on the other hand, she noted, Colombia has not been spared a push of a right-wing agenda and there are some in the country who still vehemently oppose abortion rights.

She noted that the Colombian Constitutional Court is only considering the change in law after author Natalia Bernal Cano, who wrote a book titled "The right to information about the risks of induced abortion," brought forth a case to ban abortion entirely. In her book, Cano argues that she is providing "the right to information about the risks to women's mental and physical health from the voluntary interruption of pregnancy."

The court has since used her case to consider ultra petita, or beyond what is sought.

"They have requested a lot of technical information from providers, from lawyers, from public health experts, from criminal attorneys, so that is a good sign," Avila-Guillen said. "Whatever decision they make, it's going to be informed and based on facts."