THIS IS HOME: How Child Refugees in Za'atari Learn to Cope With New Life

The camp's Makani centers provide psychosocial support to refugee children.

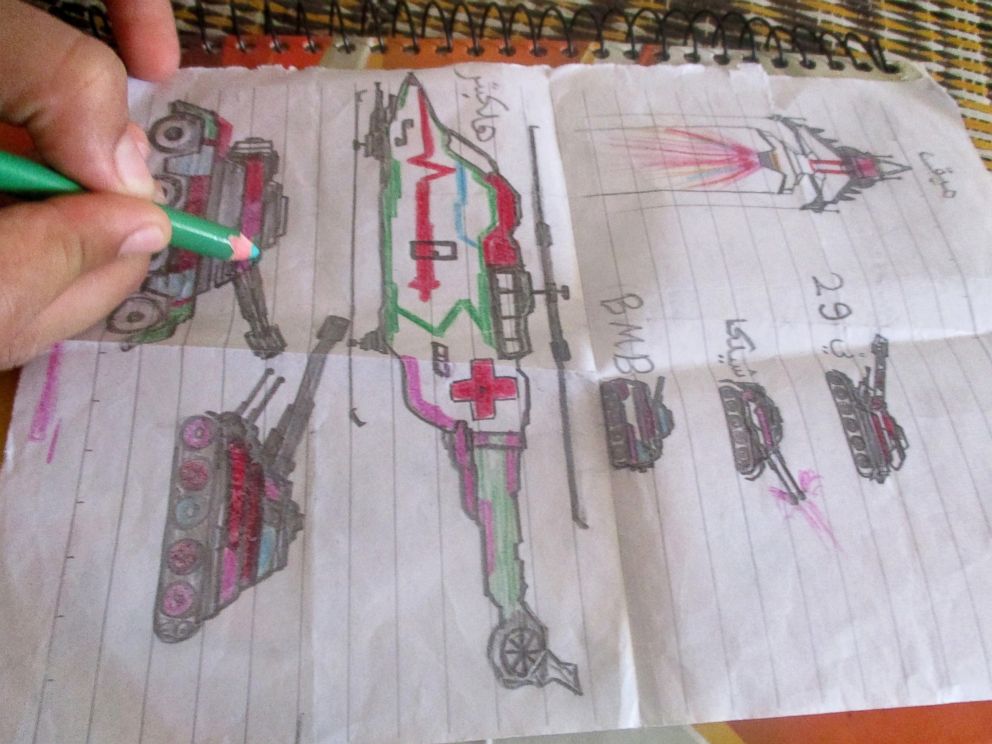

— -- Drawings of families holding hands under lopsided suns adorn the walls of an informal learning center in Jordan’s Za’atari refugee camp. The figures, dressed in brightly colored hijabs, dance around the room as children craft more artwork for display.

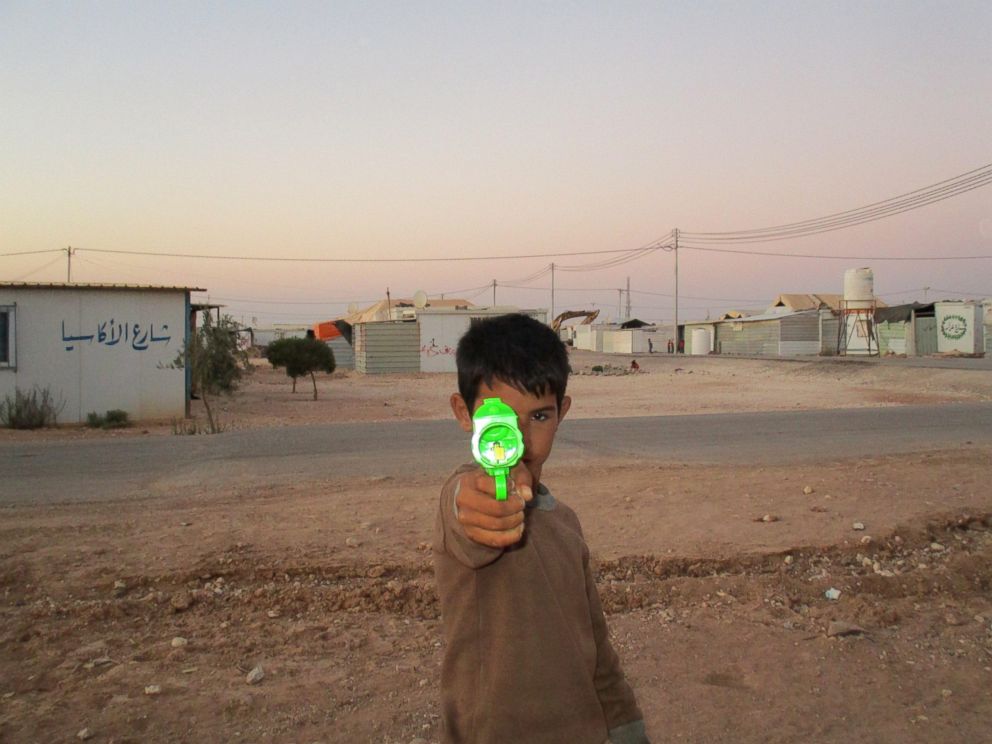

But these walls are more than just a colorful oasis in the Jordanian desert. They also house mental health and psychosocial support services for the tens of thousands of children living in the world’s largest Syrian refugee camp, who fled ongoing violence across the border in Syria.

Aya Barghash, 16, reached the camp with her mother and three siblings through the Nasib border crossing in March 2013, two years after a civil uprising erupted over Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s rule. As the local protest movement evolved into civil war, Aya’s family decided to leave their home in the southern city of Dara’a because the airstrikes from Assad’s regime had drawn closer and her mother had heard rumors that girls were being raped nearby.

When they were crossing the southern border into Jordan, Aya’s younger sister was separated from her family during an airstrike in the region. The Free Syrian Army, a rebel group, reunited them soon after.

“When they were bombing, we started hiding in basements,” Aya told ABC News in Arabic. “I am used to it. It became like a routine.”

In Za’atari, child refugees like Aya are provided with the psychosocial support services they need to help them cope and regain a sense of normality at informal learning centers called Makani (My Space in Arabic). UNICEF has established 21 Makani centers there since Za’atari, on a stretch of desert some 8 miles from the border with Syria, opened its gates to a flood of Syrian refugees in 2012.

Since last year, the Makani centers have reached more than 32,000 youths in the camp. In addition to providing psychosocial support, they offer informal education opportunities and life skills training.

“First of all, we provide safe spaces for children,” Miraj Pradhan, the head of communication at UNICEF’s office in Jordan, told ABC News. “They’ve gone through a lot. They’ve seen a lot of violence and bad things that nobody should see — children or adults.”

The children follow a schedule of activities at the Makani centers that may run from 9 a.m. to noon, for example. These activities can be as simple as drawing pictures or playing sports, but the goal is to provide a structured routine. More vulnerable children receive one-on-one counseling sessions with specialists until they can join group play.

This year, Aya participated in a play-writing activity at a Makani center. She wrote a play about how early marriage — which she has witnessed in the camp — can force some young women to be dependent on their husbands and prevent them from furthering their studies, she said.

“I tell myself how my education is my weapon,” Aya told ABC News, adding that she dreams of becoming a psychologist so she can help others.

Children of Za'atari: Photos by Syrian Refugees

Michelle May, a child protection consultant for UNICEF in the Gaza Strip, said these activities allow specialists to assess what services child refugees like Aya need without having them retell their experiences, which can be retraumatizing.

“Giving them a break from the adult world that they live in in Za’atari and just letting them be children — I think there is a therapeutic value to that,” May told ABC News.

Although refugee children like Aya have seen and experienced traumatic events, a minority of them end up requiring individual counseling at the Makani centers, May said.

“Children are innately resilient. A lot of them don’t develop PTSD,” she said. “It’s an unfortunate situation that they’re in, but a lot of the reactions that children and adults have are very normal reactions to abnormal events.”

UNICEF has expanded these services outside Za’atari, as some refugees move to towns outside the camp after a few years. Overall, Jordan has more than 200 Makani centers in towns, cities and refugee camps.

Still, establishing a new sense of normality for these children can be a challenge in Za’atari, where 80,000 people are currently living in limbo, unable to find permanent homes. Approximately 430,000 refugees have passed through the camp since it opened on July 29, 2012, according to UNICEF, which is in charge of education there, as well as water, sanitation and hygiene.

Many families never expected to be living in Za’atari for years, and life inside the camp can often feel monotonous or lonely.

“We were supposed to go to the camp just for a month, and look at us,” Aya said. “We are still here.”

ABC News, in conjunction with UNICEF, gave digital cameras to Aya and more than 50 other kids ages 11 to 18 in Za’atari and asked them to spend a week documenting daily life there. Aya said her favorite photo was one she took of her room in her family’s corrugated-steel caravan at the camp. She said she constantly redecorates her room with the art she creates at the Makani centers.

“My room is always on my mind, so I am trying to decorate this room in order to forget my room in Syria,” she said.

One thing Aya never changes about her room in Za’atari is the teddy bear that her mother gave her when she turned 11. It’s the only belonging she took with her when they fled Syria.

“For a moment, it crossed my mind that we might not go back again,” she said.

ABC News’ Phaedra Singelis, Jeesoo Park, Ronnie Polidoro, Rym Momtaz, Kirit Radia, Lena Masri and Qossay Alsattari contributed to this report.