Humans 'likely' contributed to extinction of dodo bird, giant tortoise on Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands, researchers say

The researchers studied 8,000 years of climate data from mines.

Human activity "likely contributed" to the extinction of multiple species on the islands on Madagascar and Mascarene, according to new research.

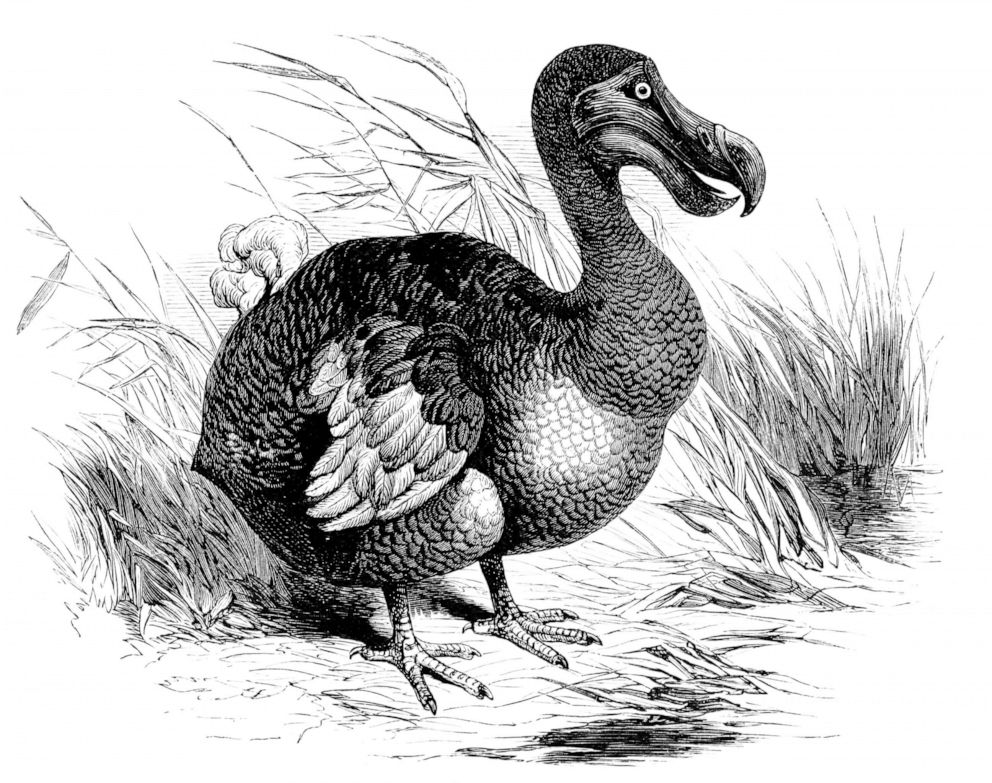

Animals native to the islands such as the dodo bird and giant tortoises had survived "repeated megadroughts" over several thousand years, but it was human activity that killed off the species for good, researchers said in a new study published in the journal Science.

The researchers studied 8,000 years of climate data from cave mineral deposits and determined that the shifting climate alone probably did not result in the species' extinction. Rather, a major increase of human-caused stressors, such as hunting and deforestation, may have contributed "significantly" to the extinctions by altering the megafauna of the region, they said.

During the past millennium, the islands underwent "catastrophic" ecological and landscape transformations, attributed to either human activity or climate change or both, according to the study.

Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands, both highly threatened biodiversity "hot spots" with "exceptional levels" of endemic species, are two of the last places on Earth to be occupied by humans. Both have lost most of their native animals weighing more than 22 pounds within the past few centuries, according to the study.

The last sighting of the dodo bird, endemic to the Mascarene island of Mauritius, was in the late 17th century, according to Nature, while the giant tortoise became extinct soon after humans arrived in Madagascar, according to the American Museum of Natural History.

Mauritius lost most of its native terrestrial vertebrates within about two centuries of its colonization, and the permanent colonization around the 1790s was marked by island-wide deforestation, the researchers said. Madagascar has lost "virtually all" of its megafauna weighing more than 22 pounds -- including giant lemurs, elephant birds and pygmy hippopotami -- over the past millennium, according to the study.

Other animal species around the world are also in trouble as a result of human activity. A report by the United Nations' Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services published last year found that humans are pushing 1 million species to the brink of extinction and that nature is declining "at rates unprecedented in human history."

The authors of the study, however, said it has "proven difficult" to investigate whether climatic shifts, human activities or both are to blame for the disappearances without precise records of biotic, environmental and cultural changes on the islands.