Inside Pakistan's fight for zero polio cases, where women are on the frontlines

Pakistan is agonizingly close to ending polio, and women are on the frontlines.

Khyal Baro didn't vaccinate her children for polio until after her youngest son, Abid Ullah, was diagnosed with the crippling disease in January 2016, when she noticed his left leg wasn’t moving and his temperature was running high.

Khyal said she had heard of polio before but, as a young married woman living in a rural village of northwest Pakistan, she didn't fully understand the consequences of not immunizing her children until it was too late for Abid, who was just 18 months old at the time.

Two months after Abid was diagnosed, Khyal's husband fell ill with a severe fever and died, leaving her to care for their polio-stricken son and three other young children without any financial support.

Abid is now a bright, talkative 3-year-old, but he still cannot move his left leg and is unable to stand or walk on his own. Khyal said she struggles to earn enough of a living to pay for Abid's medications while also raising her children as a single mom.

"It's very difficult for me," Khyal, 23, told ABC News through a translator in Pashto during a recent Skype interview from Nowshera district, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

Khyal and her four children live with more than a dozen other relatives in a joint family system, which is common in Pakistan. They share a small, mud-walled house on the outskirts of Nowshera city that has four bedrooms, one bathroom and a center living space with a kitchen. But Khyal said she still receives no support.

She's the only one who looks after Abid and is also tasked with cooking for the entire household, cleaning and caring for the other children. She makes a meager income from stitching and farm labor, she said.

"I work hard to look after them," Khyal said of her children. "Even if I don’t get to eat, I try to feed them."

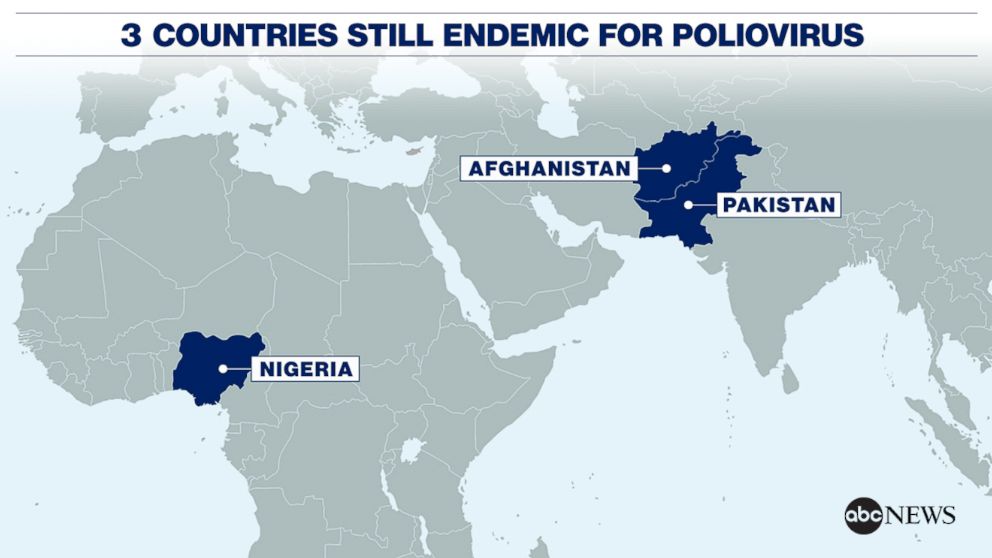

Khyal’s hardship as a mother of a child with polio is not uncommon in her home country, one of the last three polio endemic nations in the world. Poor public infrastructure, hard-to-reach communities, high population movement, cultural barriers and armed conflict have made it difficult for Pakistan to eliminate the potentially fatal virus, according to health experts.

But Pakistan has undertaken nationwide, government-backed anti-polio campaigns that have steadily decreased the number of new cases in recent years and have brought the country agonizingly close to zero.

'Strong leadership' key to eradicating polio

The general election in Pakistan this year posed yet another challenge in the fight to end polio, amid concerns the political campaigns could sidetrack vaccination efforts, according to Aziz Memon, a Pakistani businessman who heads Rotary International’s local campaign to wipe out polio. The outcome of that election was another factor that could sway the country’s progress.

"We need everyone’s support," Memon told ABC News during a recent interview in New York City. "Strong leadership in Pakistan and continued government support of polio eradication remain key to ensuring that no child will ever again have to suffer from the paralyzing effects of polio."

Imran Khan, the charismatic cricket star-turned-politician and opposition leader, is poised to become Pakistan’s next prime minister after his party’s victory in the July 25 general election. His Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party won the most seats in parliament, upending decades of rule by two of the country’s most powerful political dynasties. But his centrist party fell short of an absolute majority, so they are expected to create a governing coalition before appointing a prime minister, presumably Khan.

Khan led a campaign focused largely on anti-corruption and anti-poverty, and he has pledged to turn Pakistan into an "Islamic welfare state" by providing basic facilities such as education, healthcare and sanitation. Health experts were cautiously hopeful that his record of commitment to polio eradication and promises of improving public infrastructure could be what Pakistan needs to stamp out the disease.

"Many of us share a sense of optimism with the change and mandate given Imran Khan," said Zulfiqar Bhutta, a pediatrician and the founding director of the Center of Excellence in Women and Child Health at the Aga Khan University in Karachi, Pakistan. "Knowing him and his team, I think the key issues that we trust will improve are related to governance, corruption and evidence-based programming."

"I think his team will also probably focus more on the key bottlenecks to polio eradication in Pakistan: community engagement and buy-in and strengthening of the routine immunization services," Bhutta continued, before adding, "To be seen."

Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf has led the provincial government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa since 2013. Khan, the party's founder and chairman, helped launch a polio vaccination campaign there that same year, after the Pakistan Taliban banned polio vaccinations in the region. He has also voiced support for vaccination workers, describing them as soldiers of Islam.

"Imran Khan had a good record [in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province]," said Michael Toole, professor of international health at Burnet Institute in Melbourne, Australia. "He organized a series of high-profile polio vaccination days in Peshawar and improved security for vaccination teams. Pakistan has decentralized the health system and there is no federal ministry of health, so the polio eradication program needs strong leadership from the prime minister."

Pakistan 'closer than ever' to zero cases

Polio, or poliomyelitis, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus, which attacks the nervous system and can lead to irreversible paralysis. Polio mainly affects children under 5, though the virus can strike at any age. It’s incurable but completely vaccine-preventable.

The virus is highly contagious and can live for weeks in an infected person's feces, which can contaminate food and water in unsanitary conditions and spread to other people.

Polio paralyzed and killed as many as half a million people each year before the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) was invented in 1955, which is given by a shot in the arm or leg. The oral polio vaccine (OPV) was invented in 1961 and is given in doses of two drops by mouth, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Wild poliovirus cases worldwide have declined by over 99 percent since 1988, from an estimated 350,000 cases in over 125 endemic countries to 22 cases reported in 2017, according to the World Health Organization, which requires a nation to have no new polio cases for three consecutive years before being certified polio-free.

Polio was proclaimed eradicated in the United States in 1979. Today, Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan are the only countries in the world that have never stopped endemic transmission of the wild poliovirus.

Pakistan and Afghanistan are part of the same epidemiological block, which means health officials in both countries must work hand-in-hand to eradicate polio from the region. Although the neighboring nations have a long history of tension, there has been coordination between anti-polio teams in Pakistan and Afghanistan in recent years in an effort to curb cross-border transmission.

Eight cases of wild poliovirus were detected in Pakistan in 2017. Three cases have been recorded so far this year, according to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative.

"Pakistan is closer than ever to being polio-free," Memon told ABC News. "We want to bring it to zero cases and then maintain it at zero."

Just a few years ago, Pakistan was home to nearly all of the world’s polio cases.

From 2012 to 2015, vaccinators were unable to access a mountainous, former semiautonomous region of northwest Pakistan. The so-called Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) were controlled by militant groups, such as the Pakistan Taliban, which barred polio vaccinations amid fears the campaigns were used by Western forces as a cover for espionage ahead of drone strikes. Children in these isolated tribal areas were not immunized at all.

In 2014, 306 new cases of the wild poliovirus were recorded in Pakistan and the government declared it a "public health emergency."

Health organizations, in partnership with the Pakistani government, have since mobilized hundreds of thousands of staffers and volunteers in an effort to vaccinate every eligible child in Pakistan, especially those who are on the move and have routinely missed immunizations. They administer vaccines at health centers and in homes. They also setup makeshift vaccination clinics at transit hubs, border crossings, army posts and police checkpoints across the country.

Children’s fingers are marked with indelible ink after they have received the vaccine.

But some families refuse immunizations. About two in 10 vehicles flagged down during vaccination campaigns in Pakistan don’t participate, according to Rotary International, a partner agency of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, along with the World Health Organization, the United Nations Children’s Fund, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"The main barrier to zero cases remains the Pakistan Taliban, which continues to maintain a ban on vaccination in areas they control, which include FATA and even parts of Karachi," Toole told ABC News.

In May, Pakistan's national assembly passed a landmark constitutional amendment to merge the restive FATA region with the neighboring Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, which has been hailed as a step toward bringing the tribal areas into the mainstream.

Women on the frontlines of Pakistan’s anti-polio campaign

Tayyaba Gul, a member of the Rotary Club of Islamabad, runs a Rotary-funded health center in Nowshera district where her team of about 100 women vaccinators aim to close the cultural gap that pushes up refusal rates. They work in neighborhoods within tribal border regions among ethnic Afghan refugees, offering OPV drops while trying to educate mothers on the devastating effects of polio and convince them that immunizations are a normal part of postnatal care.

Many mothers in these areas live in joint family dwellings and are socially isolated from life outside due to their duties at home. The cultural and religious norms in the mostly Muslim region typically prevents women from leaving their house without the permission and company of a male relative.

Gul, who has decades of experience working in the development sector, said it usually takes multiple house visits, but having the female vaccination workers connect and communicate with the women of a household is key in persuading that family to immunize the children.

In joint family systems, all household members are often involved in deciding whether to accept vaccinations. Building a trusting relationship with the women, who spend the most time at home and with the children, helps open up the conversation with the men, who are the heads of the household, Gul said.

"In Pakistani culture, women are not talking easily, especially in the rural [areas]. They are not comfortable talking with men. They feel comfortable with women," Gul told ABC News in a recent Skype interview from Pakistan's capital, Islamabad. "If we motivate them, we can do it. We can achieve the result."

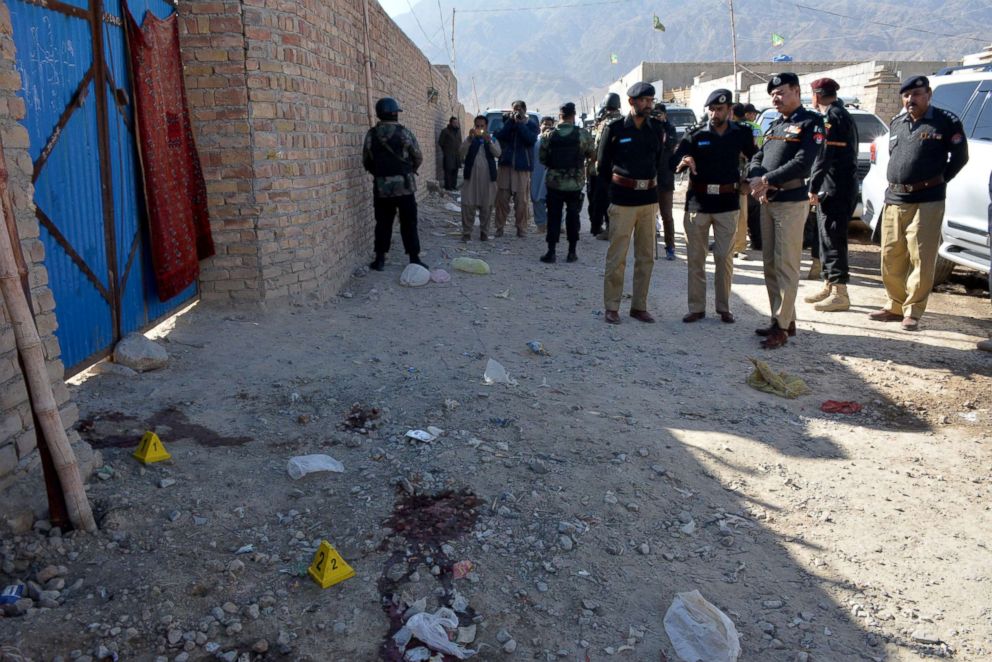

However, frequent attacks on anti-polio teams by the Pakistan Taliban and other militant groups have made it dangerous to enter certain remote tribal areas. Dozens of vaccination workers have been killed in recent years.

In January, a mother and daughter who were volunteering in a polio immunization campaign were shot dead in the southwest province of Balochistan. No group immediately claimed responsibility for the attack at the time.

"Some of the areas we are not covering, but [the] government is providing us police security," Gul said. "Especially for those areas if the women [vaccinators] cannot move there alone and especially during campaigns, we are jointly going there and covering those areas."

"Some of the areas is not easy, still not easy, for the lady health workers to go there," she added.

Despite the risks, Gul said she is not afraid.

"This is my mission,” she told ABC News. "This is my contribution."

A mother's hope

Khyal is among the many mothers with whom Gul has cultivated a relationship since her son Abid was diagnosed with polio.

At first, Gul said, Khyal's family refused to open their door whenever vaccination workers came through their neighborhood. And Khyal's late husband, a conservative Muslim, wouldn't allow her to take Abid or their other children to the health clinic in Nowshera for immunizations, even after Abid showed symptoms of polio.

So Khyal went in secret, Gul said.

"These women have no exposure outside the home, what is going on, because they have no mobility," Gul told ABC News. "The family male members [are] not allowing the female to go outside alone ... and they have no discussions regarding what's going on in the world, what's going on in Pakistan."

Khyal’s husband was born in Pakistan to parents who were refugees from Afghanistan, according to Gul. Up until his death in 2016, he worked as a taxi driver and made regular trips across the long, porous border to his family's home country, which Gul said could be how his son contracted the virus.

"This disease is traveling," Gul said.

Upon seeing firsthand how the disease has left her son partially paralyzed, Khyal has been seeking treatment for Abid as much as she can and she gets her other children routinely vaccinated. Her nieces and nephews who live in the same household also receive OPV drops, she said.

"I am really scared of polio. I make sure to vaccinate my other kids," Khyal told ABC News. "I take [Abid] everywhere, to every doctor anyone recommends in hope that he gets better."

Dressed in a blue burqa that concealed her face, the mother held her fussy toddler during the late night Skype interview, his wide eyes slowly closing and opening until he eventually dozed off in her arms. Abid appeared healthy, though his left leg was completely motionless.

Khyal said she hopes Abid, like other children, will be able to go to school when he’s old enough and pursue an education. Then, she plans to help him open a shop so he can make a living.

Although Gul has gently tried to explain that Abid's paralysis is likely permanent, Khyal said she still prays her son will one day be able to stand on two feet and walk.

"God will do whatever is destined for him," she said.

ABC News' Habibullah Khan contributed to this report from Islamabad, Pakistan.