North Korea crisis becoming unsolvable, experts warn, as Trump heads to Asia

The standoff is closer to war than at any other time in recent years.

— -- All it would take is a miscalculation — an error in interpretation by a single soldier, for example — to plummet the United States, North Korea and the region into war, some analysts warned.

Imagine a North Korean surface-to-air missile operator who sees a U.S. B-1B bomber flying closer and closer to his country’s airspace and, after years of anti-U.S. propaganda that has portrayed an aggressive invader, thinks his country is at risk. What was a defensive military exercise, by U.S. accounts, becomes an international incident, with two pugnacious leaders — who don’t like to be seen as backing down — risking a wider conflict.

While it may seem theoretical, a growing chorus of foreign policy experts across the political spectrum are warning that the standoff is closer to war than at any other time in recent years. Some even argue the problem is becoming intractable, if not impossible to solve, which makes military action that much more likely.

As President Donald Trump heads to Asia on Friday for a 12-day trip, the North Korean crisis will be a top priority, especially because the United States is “running out of time,” according to his national security adviser, H.R. McMaster.

“We are in a race to solve this, short of military action,” McMaster said Oct. 19, adding that Trump “is not going to accept this regime threatening the United States with a nuclear weapon.”

North Korea is heading toward that capability — an intercontinental ballistic missile that can carry a nuclear warhead — so quickly that CIA Director Mike Pompeo said recently the United States “ought to behave as if they’re on the cusp.”

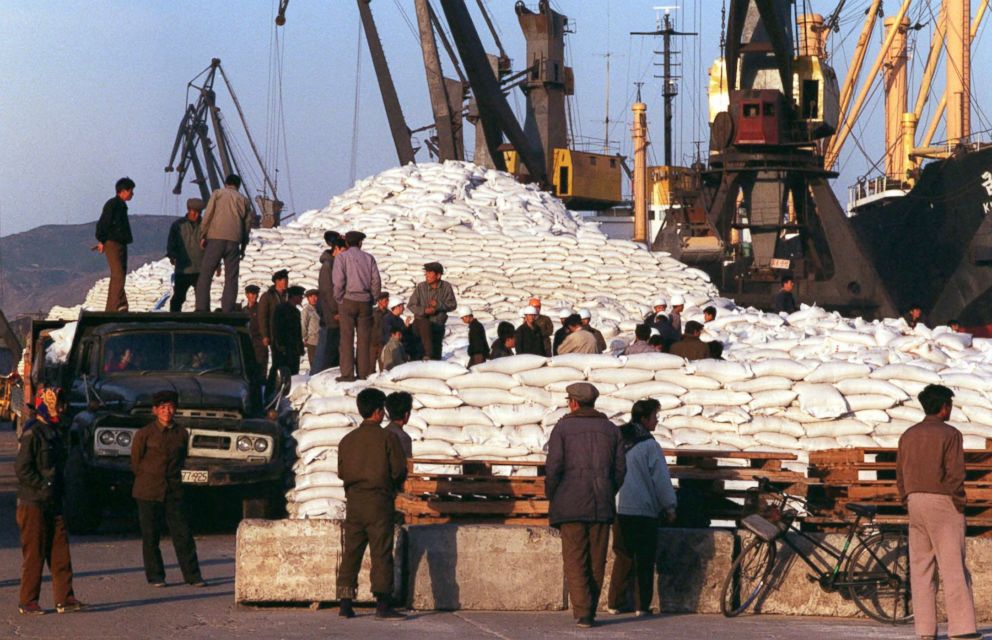

The seesaw relationship between North Korea and the United States

Such stark warnings are a reflection of their boss’s language too.

“They won’t be around much longer,” Trump tweeted of the regime on Sept. 23, days after he warned in his U.N. General Assembly address the United States could “totally destroy North Korea.”

He later tweeted, “Clinton failed, Bush failed, and Obama failed. I won’t fail.”

But it’s precisely because of his rhetoric that the United States is more tightly boxing itself in with Kim Jong Un’s regime, according to interviews with over a half-dozen experts and former administration officials.

A dangerous deadlock

In particular, North Korea is racing toward the very capability the White House says is unacceptable. And North Korea’s statement that it will not negotiate until it has a nuclear-armed ICBM is a sign that Kim sees it as a necessary guarantee of his security against what he calls increased U.S. aggression.

“Kim Jong Un has made it very clear that he considers his nuclear deterrent to be the key to his survival and the key to deterring what he perceives to be a hostile United States,” said Robert Einhorn, a longtime diplomat who served as a State Department special adviser for nonproliferation and arms control.

He added, “I just don’t think that we’re going to be able to mount the sanctions campaign that’s going to persuade Kim Jong Un to give it up and to give it up soon.”

But the deadlock could mean military action of some sort is much likelier.

“The incentives to retain this capability may be much stronger and, because of what the administration has said about the unacceptability of their possessing the capability to deliver nukes to the United States, seems to have made a military solution increasingly hard to avoid,” said Alexander Vershbow, the U.S. ambassador to South Korea under President George W. Bush and the assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs under President Obama.

Vershbow added that Kim, who is more assertive than his father, North Korea’s previous ruler, has “internalized the lessons of what happened to Saddam Hussein or Muammar Gaddafi,” who were overthrown by U.S.-led interventions.

Kim views his nuclear weapons as a way to make sure that doesn’t happen to him, experts said.

The administration’s demands may be making the situation more difficult. Its insistence that North Korea denuclearize and that talks begin on that condition are not helping bring North Korea to the table, said several experts, as well as the top Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

“The White House is approaching North Korea in an increasingly binary way — either North Korea backs down and agrees to diplomacy on our terms or we take military action and risk war,” Sen. Ben Cardin, D-Md., was expected to say on the Senate floor today, according to an advance copy of his remarks.

The threat of silence

What makes the situation even more dangerous — and the threat of an escalation more likely — is the lack of communication, according to some officials.

“Wars have started for lesser reasons than the big egos of leaders,” said Mackenzie Eaglen, a fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute who has worked at the Pentagon and on Capitol Hill. “It’s easier than most Americans think to stumble into war based on confusion or misinterpretation of some hostile action by one party perceived wrongly by the other.”

Mike Fuchs, a deputy assistant secretary for East Asian and Pacific affairs under Obama, described it as speaking different languages: the foreign policy by tweets and movement of military assets by the United States and North Korea’s provocative tests and bellicose rhetoric.

“Those types of actions on both sides, combined together without a direct diplomatic high-level regular channel to discuss a way forward, is a recipe for a disaster,” he said.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has said there are some lines of communication between the two, but the State Department denied a Reuters report Tuesday that talks are more extensive than a channel at the United Nations in New York focused on three U.S. citizens held captive by North Korea.

“While we do maintain a channel to North Korea to discuss detained American citizens, we are not pursuing broad talks with North Korea at this time,” a State Department spokesperson told ABC News. “We have not ruled out doing so in the future, but only if and when North Korea’s behavior significantly improves.”

The State Department declined further comment, but the administration previously blamed the lack of communication on North Korea’s continued nuclear and ballistic missile tests.

“North Korea has shown zero inclination to engage in substantive talks with anyone in the world on this subject,” a senior administration official told reporters Tuesday. “The operative question is, why is that the case?”

Trump’s tweets making it worse?

Trump’s comments may be responsible as well, at least in part.

“President Trump has personally insulted their leader, and in their system that’s a terrible sin,” Einhorn said. “Apparently, in efforts to reach out to them, they cite this as one reason why it’s impossible for them to talk — the ‘Little Rocket Man’ and similar taunts.”

But some argue that Trump’s remarks are not taken that seriously.

“Most countries, even the North Koreans, have taken the measure of Donald Trump, and they know that whatever comes out of his mouth has nothing to do with whether we would or whether we wouldn’t” act, said Chris Hill, who, as the assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs under George W. Bush, was head of the U.S. delegation to six-party talks on North Korea’s nuclear program.

But that itself is a danger that could lead North Korea to overstep, according to Jung Pak, a senior fellow at the nonpartisan Brookings Institution who served in the CIA and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

“If Kim does not believe in the credibility of the U.S. military threat, being inured to the empty bluster of President Trump, he could potentially be goaded by additional tweets or U.S.–South Korean military shows of force into following through on the threats,” she wrote Monday.

Which way forward?

The dangerous impasse had led many, Obama’s national security adviser Susan Rice among them, to argue that the only way forward is to accept and deter: accept the reality of North Korea’s nuclear program and deter the country from attacking the United States and its allies.

But the Trump administration views that as anathema.

“Accept and deter is unacceptable,” McMaster said recently. “The only acceptable objective is denuclearization.”

Accept and deter would be “the beginning of the end of our alliances,” Hill told ABC News.

Instead, even critics of the administration argue that the only way to resolve the crisis long term is to stay on the current path, regardless of what Trump and Kim say.

“I don’t see we have a choice but to continue this and to try to be closer to our allies and really sit down with the Chinese and explain why we’re not going to put up with this,” said Hill, who remains convinced that the United States can change Kim’s calculus and, eventually, end his pursuit of nuclear weapons.

The status quo could work to the U.S.’s advantage, according to Kori Schake, who served in George W. Bush’s administration at the National Security Council, Pentagon and State Department. “If we are frozen in that standoff, that leaves time for economic sanctions to work” she said.

There is more that can be done too, from the White House’s using secondary sanctions to ramp up the pressure on China and Russia — a “bad idea whose time has come,” Hill said — to more U.N. or U.S. sanctions.

A bipartisan group of senators reached an agreement late Wednesday to do just that, with a new bill to target North Korea’s financial supporters.

But ultimately, it comes down to time and whether the administration that blasted its predecessor’s policy of strategic patience has the patience for its own peaceful pressure campaign on North Korea to work.

At this point, its urgent rhetoric “is inconsistent with the time required for the tools they are using — economic sanctions and diplomacy — to produce results,” Schake said, calling it a “timeline problem” that leaves the Trump administration “not likely to succeed on this line of policy.”

In the end, that’s as much a political decision as a policy one, keeping the president happy when he is demanding results. For now, the clock is still ticking.