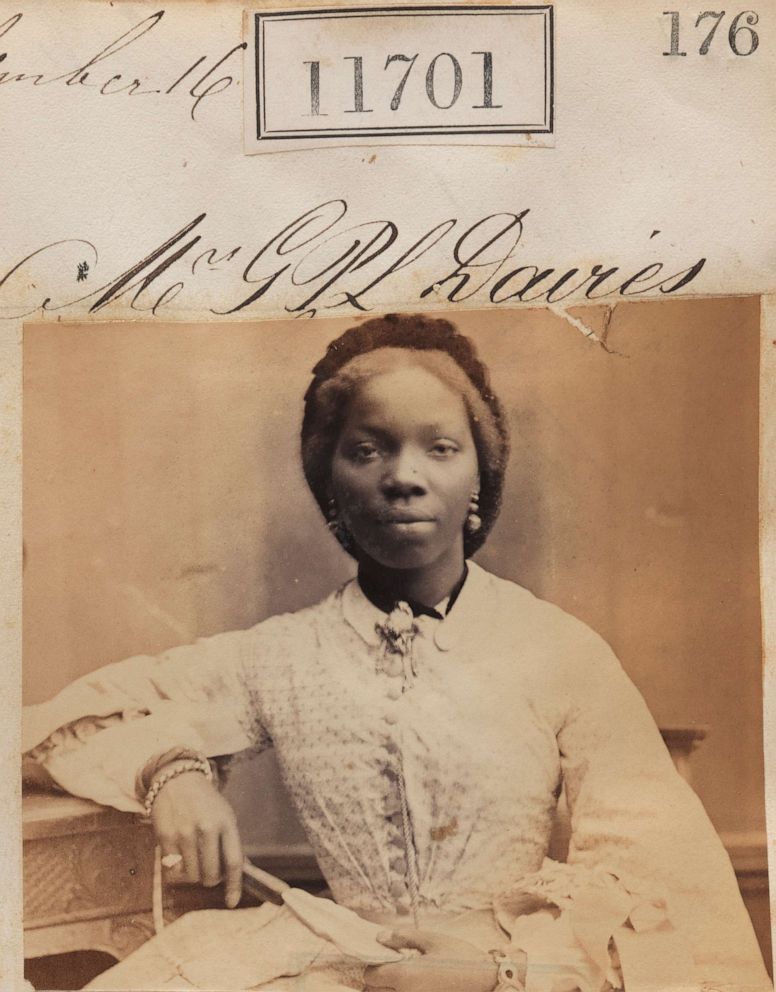

New portrait of Queen Victoria's African goddaughter on display

The portrait was commissioned to celebrate Black British figures from history.

LONDON -- A new portrait of Queen Victoria’s African goddaughter, Sarah Forbes Bonetta, has been unveiled at the 19th century monarch’s home on the Isle of Wight, as part of the conservation charity English Heritage’s contribution to the U.K.’s Black History Month this October.

Bonetta, who was originally named Aina, was the daughter of a West African ruler. She was sold into slavery at just five years old before she was brought to England in 1850 as a "diplomatic gift." Two years later she caught the eye of Queen Victoria who paid for the “sharp and intelligent” child’s education and became her godmother after several meetings over the years with the Queen, according to English Heritage.

Bonetta went on to marry James Davies in England, a merchant born in Sierra Leone who was the son of liberated slaves, and named her first daughter after the Queen. Bonetta died of tuberculosis in 1880.

The new painting will be on display at the Queen’s former seaside residence, Osborne, throughout October, as part of a wider series of portraits to commemorate Black people who have been “overlooked” in British history.

Hannah Uzor, who painted the portrait, said she was interested in “exploring those forgotten black people in British history” through her art.

“What I find interesting about Sarah is that she challenges our assumptions about the status of black women in Victorian Britain,” Uzor said. “I was also drawn to her because of the parallels with my own family and my children, who share Sarah's Nigerian heritage.”

“To see Sarah return to Osborne, her godmother’s home, is very satisfying and I hope my portrait will mean more people discover her story,” she added.

Other Black figures from British history, such as Septimus Severus, Rome’s African-born emperor, and James Chappell, a 17th century servant., will also feature in the series.

“There are a number of Black figures from the past who have played significant roles at some of the historic sites in our care but their stories are not very well known,” English Heritage’s curatorial Direct Anna Evis said. “Starting with Sarah, our portraits project is one way we’re bringing these stories to life and sharing them with our visitors.”