Terror of gang violence drives migrant caravans northward

Terror of gang violence drives migrant caravans northward

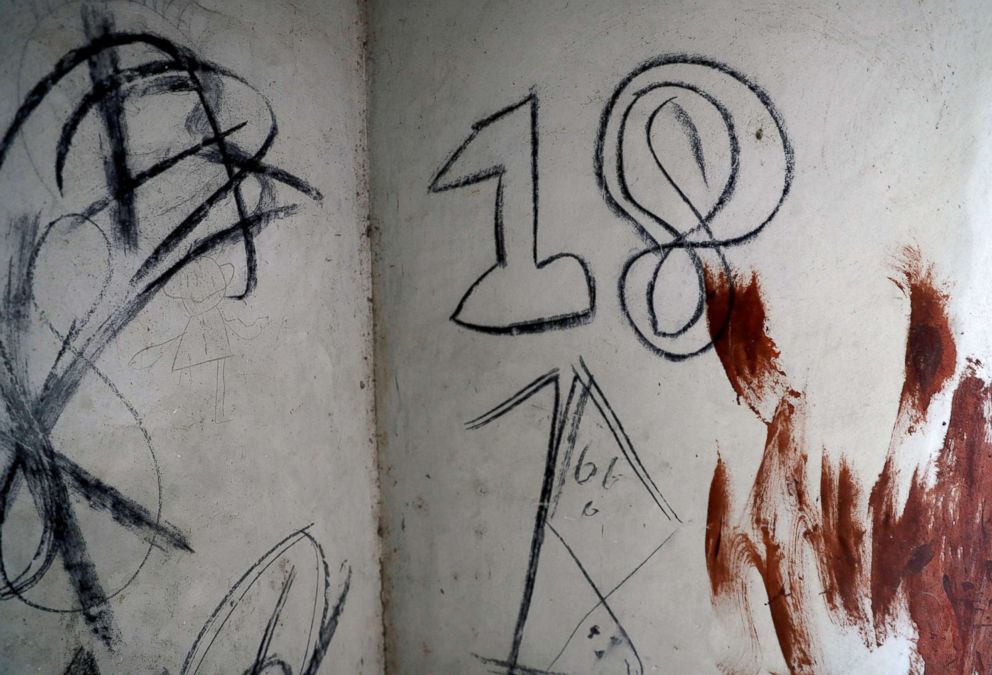

The following contains graphic content. Viewer discretion is advised.

Former Honduran policeman Ivan says he moved homes so many times to escape the street gangs that terrorize his Central American country that he lost count. Fearful his sons would have to join the gangs or be killed, he eventually joined thousands of Hondurans fleeing to the United States.

The 45-year-old, who asked to be identified only by his first name, is journeying through Mexico in a caravan of several thousand mostly Honduran migrants who are fleeing violence and poverty for a better life in the United States.

U.S. President Donald Trump has declared the caravans an "invasion," and has sent some 5,800 troops to "harden" the border, including with barbed wire.

Ivan, fearful to tell his story, is watchful for gang tattoos or slang that might suggest fellow migrants were associated with his persecutors back home.The former policemen said the final straw in Honduras came when gang members put a gun to his 15-year-old son Yostin's head.

They wanted Yostin and younger brother Julio, 13, to join them, threatening death if they refused, Ivan said during a break in the caravan's northward journey at temporary camp in a Mexico City stadium.

So when a caravan set off on Oct. 13 from the crime-racked Honduran city of San Pedro Sula, where the family was hiding with friends, they never hesitated. Reuters was not able to independently verify their story.

However, their motives echo others in the caravan and are a reminder of the influence the gangs called 'maras' wield across El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala despite almost 20 years of efforts to crush them.

Homicide rates have fallen in Honduras since 2016, as a consequence of initiatives that include prison reform, the creation of a specialized anti-gang security force, and increased resources for law enforcement.

In 2017 there were 42 murders per 100,000 residents in Honduras, compared to 57 per 100,000 in the prior year, according to statistics from the government and the World Bank.

Still, the murder rate in Honduras remains one of the highest in the world and catastrophic. Some international aid organizations such as the Norwegian Refugee Council operate in the country with the same precautions as in war zones, and say inhabitants face the same dangers.

At the U.S. border barbed wire laid by soldiers deployed by Trump awaits the caravan to dissuade the migrants from crossing illegally. New rules curtailing asylum claims also increase the chances they will be deported.

A return home terrifies many, including Ivan. Removed from his job of 27 years in a police purge two years ago, he says he fears death in Honduras.

The purge removed more than 4,000 officers, or close to a third of what is currently a 14,000 strong force, according to Commissioner Jair Meza, spokesperson for the Honduran Security Ministry.

Ivan says the purge removed good police as well as bad, while leaving the former officers exposed to revenge attacks from gangs they once pursued.

"They know us and so they hunt us down," he said.

Meza said police who were removed were subject to polygraph tests and background checks before being selected. Age and performance were other considerations.

In Honduras, violence can strike at any time.

On the cocaine transit corridor to the nearby port of Puerto Cortes, San Pedro Sula was for years one of the world's most dangerous cities. Its morgue was so full of corpses that locals said their smell permeated the streets.

On a night in late July, a family sat on the side of a highway in San Pedro Sula, a few feet from a crime scene.

Fransisca Sislavas waited stone-faced between her son, Rony, 2, and her daughter, Brittany, 4. The girl's ankle was splattered with her father's blood.

Minutes earlier, Sislavas had been sitting beside her partner and their children in a taxi. She struggled to explain his death.

"I don't know. Why? How? I just don't know," she said.

For some Hondurans who fail in their pursuit of the American Dream, deportation can mean an entrance into gang life.

Henry Fernando, (not pictured), an active member of MS-13, also known as Mara Salvatrucha, said he walked more than 3,000 miles and almost died in the desert crossing from Mexico to find his mother, who had left him for Virginia.

Quickly deported, MS-13 was the only home he found, he said, recalling the girlfriends, or "jainas", that leaders offered, serving as payment for the marijuana and crack cocaine he sold. Reuters was not able to independently verify his story.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement said it was unable to trace Fernando's deportation based on the information Reuters was able to provide.

Nine years later, now 28, he has a young son, and dreams of leaving the gang. His home, visited by Reuters, was a rented room barely wider than his mattress, up a rickety ladder in the middle of a pigsty. He had moved up the MS-13 ranks, but remains mired in poverty.

Fifteen people interviewed by Reuters, either active in the gangs or in stages of reforming, described only two ways out: join an Evangelical church or death.

All of them said they joined the gangs as boys from broken homes in broken neighborhoods.

Story by Delphine Schrank