Why is the US still in Afghanistan?

Two thousand soldiers, hundreds of billions of dollars and 17 years so far.

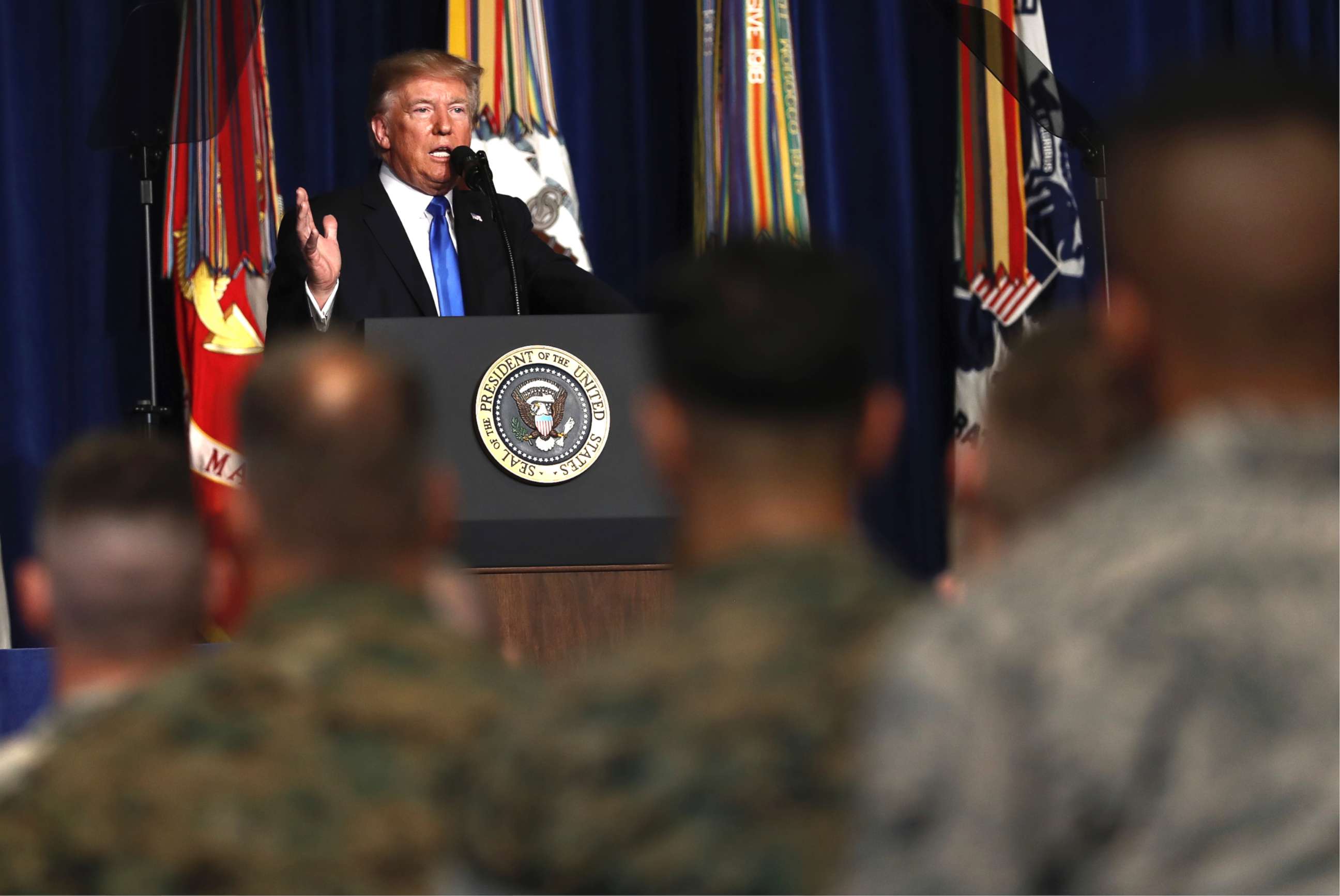

—London -- On Aug. 21, 2017, President Donald Trump addressed American soldiers and Army generals at the Fort Myers military base in Arlington, Virginia, announcing that he was taking a new approach to the war in Afghanistan – the longest war in U.S. history, and its costliest since World War II.

Trump said American service members would be withdrawn on a "condition-based" approach and not according to a timetable. “One way or another these problems will be solved,” he said. “In the end, we will win.”

To that end, the number of U.S. troops serving in Afghanistan would increase by 3,000, bringing the total number to 14,000. The U.S. military mission in Afghanistan is to train, advise and assist the Afghan military who are doing the actual fighting against the Taliban and ISIS, but U.S. military personnel can find themselves in combat situations while carrying out the advisory mission.

Trump, in a shift from his predecessor, gave more power to military leaders in carrying out operations, bestowing additional authority on the Pentagon. On April 13, 2017, the U.S. military deployed a GBU-43, nicknamed “the mother of all bombs,” on an ISIS tunnel in Afghanistan. It sent a strong signal about how the new president was positioning himself on the fight against terror.

17 years into the campaign, what is the situation like currently in Afghanistan?

Trump, like many Americans, has frequently called into question U.S. involvement in the Middle Eastern country.

Violence in Afghanistan has risen dramatically since the phased withdrawal of allied troops in 2014. The Taliban insurgency has increasingly gained ground, carrying out successful terror attacks across the country and now, according to a new study, has a presence in 70 percent of Afghanistan.

The study’s findings were flatly dismissed this week at the Pentagon. Joint Staff Director Lt. Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr. estimates that 60 percent of the country is under government control, with 10 or 15 percent controlled by the militants.

Last month just under 200 people were killed in four separate attacks carried out by groups apparently including the Taliban, ISIS-Khorasan (the terror group’s Afghan affiliate) and the Haqqani network.

Civilians, aid workers and Afghan soldiers were targeted in the January attacks. A flurry of violence has brought renewed focus on the progress Trump’s strategy is having there.

Why is the U.S. in Afghanistan?

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, President George W. Bush vowed vengeance against the perpetrators who were quickly identified as being linked to al Qaeda – the extreme Salafist terror group founded by Osama bin Laden and based in Afghanistan.

After the atrocity, Bush, speaking to a joint session of Congress, gave a stark warning to the Taliban, a Sunni jihadist movement which aimed to create an Islamic emirate in Afghanistan.

“The Taliban must act, and act immediately. They will hand over the terrorists, or they will share in their fate,” he said.

Bush’s "War on Terror" would go on to cost more than $840 billion in Afghanistan alone, according to an analysis by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The Taliban, once an effective and enduring insurgency that ruled in Afghanistan, was toppled after the U.S. invasion in 2001.

Today the group is joined by ISIS’ branch in the country and their longstanding allies al Qaeda and the Haqqani network.

Why haven’t these groups been defeated after 17 years?

“The Taliban is not a military group – it’s a lifelong commitment to a struggle. You can’t wait for their troops’ rotations to end. You can’t wait for their term of enlistment to expire. There is only death or success,” said Malcolm Nance, a U.S. Navy intelligence veteran who served in Nangarhar Province on the eastern border with Pakistan.

The myriad tribal and ethnic groups that live in Afghanistan have become disassociated with the central government in Kabul.

Andrew Exum, a former senior Department of Defense official in the Obama administration who served in Afghanistan as an army officer, said that the enduring reality of the Taliban and other established militant groups in the country can be attributed, among other things, to the weakness of the state – especially one that ignores many of its citizens living in remote tribal lands far away from the capital.

“Fighting an insurgency on a very local level, especially in areas such as eastern Afghanistan where the people don’t necessarily have any connection to the central government, makes it incredibly hard to achieve your goals there,” he said.

Why have there been so many attacks this year?

January was exceptionally violent month in the country -- just six months after Trump's plan was implemented.

Trump railed against the latest attacks, telling members of the UN Security Council at the White House this week that he was not interested in any more talks with the Taliban: "There’s no talking to the Taliban. We don’t want to talk to the Taliban. We’re going to finish what we have to finish," he said.

The group warned that his rhetoric would lead to more bloodshed.

James B. Cunningham, who served as U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan from 2012 to 2014, told ABC News that it is too soon to judge what impact the new strategy would have on the ground.

"The implications of Trump’s seeming rejection of talks with the Taliban remain to be seen. He did say talks would not be possible for a long time, and that is likely the case," Cunningham explained. "But the essence of his own strategy is to use new forces and authorities to work with the coalition and the Afghans to create the conditions for eventually getting the Taliban to stop the killing and end the conflict — which is the right thing to do...a political solution at the end must be among Afghans."

Negotiations between the Afghan leadership and the militant group started in 2014. The group, unlike ISIS in Afghanistan, continues to push for control for what it sees as its "rightful share" of the country.

ISIS’s strategy in the country appears more opportunist than its attack on Save the Children in Jalalabad may demonstrate. The militant group is vying with its rivals to establish its place as a relevant and threatening presence.

What is Pakistan’s role in this?

Pakistan has been one of America’s most important allies in the fight against terror. But it has not been smooth sailing.

Relations were severely damaged when President Obama made the call to conduct a Navy SEAL raid on a Pakistani military compound in Abbottabad in 2011, resulting in the death of Osama bin Laden.

The Pakistanis were not notified of the operation before it was carried out. A government commission looking into the raid condemned what it described as “an American act of war” that demonstrated Washington’s “contemptuous disregard of Pakistan’s sovereignty.”

The issue of drone strikes is also a bone of contention between Pakistan and the U.S. On Jan. 24 Pakistan condemned a U.S. drone strike which officials said targeted militants in the Haqqani network in the northwest of the country. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that such unilateral action was detrimental to cooperation against terror and added that the site was a refugee camp for Afghan nationals.

Pakistan, one of the largest recipients of American aid, was aghast after UN Ambassador Nikki Haley announced plans to indefinitely suspend $225 million in foreign military aid at the start of January this year, accusing Islamabad of “playing a double game for years” with its selective support for various militant groups operating on its soil.

Some attribute the recent surge in violence in Afghanistan with the move. British diplomat Arthur Snell, previously stationed in Helmand province, said it is perfectly plausible that Pakistan may have responded to the withholding of aid by taking the pressure off counterterror efforts on its border with Afghanistan – likely easing the movement of militants and their supplies.

“That is why they have a relationship with the [Afghan] Taliban – it allows them to project power beyond their borders in an asymmetric way,” he told ABC News.

Ambassador Cunningham agrees that Pakistan has a connection to the latest attacks.

"These crimes against humanity, the targeting and slaughter of innocents, are undoubtedly guided by the Haqqani network and the senior Taliban leadership operating from Pakistan," he said. "Pakistan’s role is critical if the Taliban leaders are to come to the conclusion that continued terror is not going to prevail."

But the Pentagon has strongly denied there is any significance behind the attacks.

“For every attack that’s carried out many many many are stopped, many are prevented from occurring. So to think that you are going to have exquisite timing on when an attack is going to occur is probably a bridge too far for the Taliban to have,” Lt. Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr. said.

Pakistan has long suffered from atrocious attacks by the domestic Pakistani Taliban, a separate entity that its citizens are deeply hostile toward. Many, however, are sympathetic and see the Afghan Taliban as a legitimate resistance to the prevalent foreign forces operating in Afghanistan.

The Pakistani military and security apparatus have been more successful in dealing with the Pakistani Taliban than the Afghan forces have with their equivalent.

As long as the Afghan Taliban continue to use Pakistani soil as a base, the complicated nature of Pakistan’s role in fighting terror in the region will continue to be a thorn in America’s side.