1st major court test for DOJ special counsel investigating origins of Russia probe

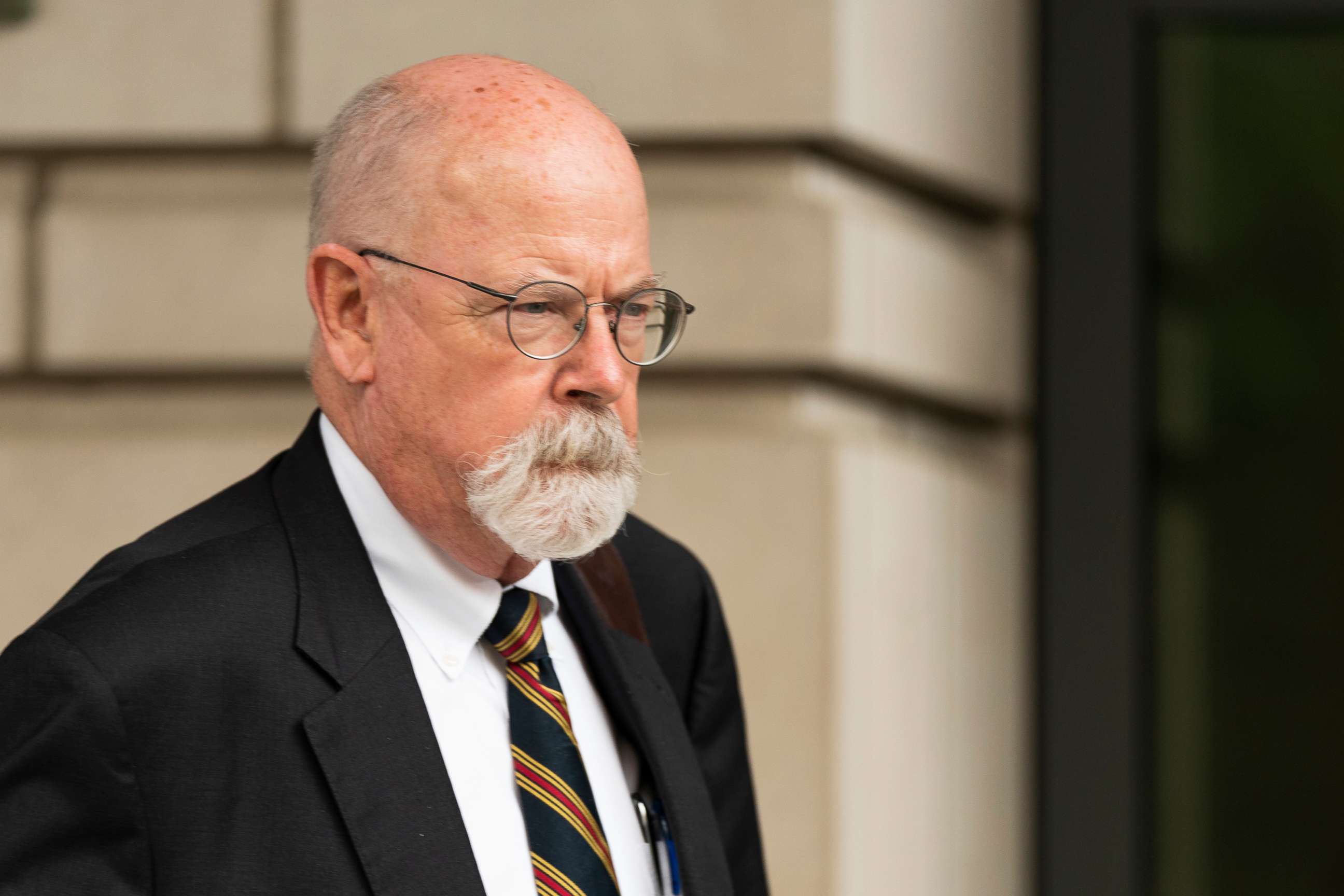

John Durham is prosecuting Democratic lawyer Michael Sussmann.

The Justice Department special counsel investigating the origins of the probe into Russia's interference in the 2016 presidential election is facing his first major test in federal court this week, with the start of a criminal trial against a Democrat-linked lawyer charged with lying to the FBI.

Prosecutors are seeking to convince a jury that lawyer Michael Sussmann lied in bringing forth a tip to a senior FBI official in September 2016 about potential connections between then-presidential candidate Donald Trump's company and a Russian bank, by allegedly telling the official that he was not working on behalf of any client at the time.

According to John Durham, who has been investigating the Russia probe for more than three years and was appointed special counsel by former Attorney General William Barr just before Barr’s resignation in 2020, Sussmann was in fact bringing the info to then-FBI general counsel James Baker as part of Sussmann's work for Hillary Clinton's political campaign and a technology company executive who had worked to assemble the data.

This "led the FBI General Counsel to understand that Sussmann was acting as a good citizen merely passing along information, not as a paid advocate or political operative," Durham's indictment alleges.

"Many people have strong feelings about Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, but we are not here because these involve allegations involved either," Durham prosecutor Deborah Shaw said in opening arguments Tuesday. "We are here because the FBI is our institution. It should not be used as a political tool for anyone."

The alleged lie by Sussmann had an impact on how the FBI ultimately investigated the allegations, Durham has claimed, which involved data showing a potential communications channel between computer servers for the Trump Organization and the Russian-owned Alfa Bank. The FBI eventually determined the data did not show anything nefarious.

A key piece of evidence Durham's team has said supports their case was revealed only last month. Prosecutors will point the jury to a text message that Sussmann allegedly sent to Baker the night before they met in which Sussmann wrote, "I’m coming on my own – not on behalf of a client or company – want to help the Bureau."

While the charge against Sussmann is narrow, through their 27-page indictment and hundreds of pages of court filings in the months since Sussmann was indicted, Durham's prosecutors have sought to allege a broader potential conspiracy regarding efforts by Clinton's campaign and other political operatives to spread unverified allegations about possible ties between Trump, his campaign and the Russian government.

"No one should be so privileged to have the ability to walk into the FBI and lie for political ends," Shaw said Tuesday, adding "whether we hate Donald Trump or like him," all have to agree lying to FBI is illegal.

Sussmann's attorneys have disputed he told Baker at the meeting that he was not bringing the information forward on behalf of a specific client, and have argued that there's no evidence such a statement had a measurable impact on how FBI agents eventually investigated the allegations.

In opening statements Tuesday, Sussmann's attorney Michael Bosworth said while Sussmann was representing Clinton's campaign "generally" in the fall of 2016 -- and that representation included work on the Alfa Bank data that was brought to him by tech executive Rodney Joffe -- his meeting with the FBI was not part of his work for the Clinton campaign.

On the contrary, according to Bosworth, Sussmann sought the meeting to give the bureau a heads up on a story the New York Times was working on about the Alfa Bank data at the time, so it wouldn't be caught "flat-footed."

While Durham's team argues Sussmann was hoping the meeting would later result in an "October surprise" news story about the FBI opening an investigation on potential ties between Trump and Russia -- Bosworth said that as a result of the meeting, the FBI was actually able to persuade the Times not to run the story.

In other words, according to Bosworth, Sussmann's meeting generated the "opposite" result of what the Clinton campaign would have wanted at the time.

Sussmann's attorneys have previously accused Durham's prosecutors of trying to promote a "baseless narrative that the Clinton Campaign conspired with others to trick the federal government into investigating ties between President Trump and Russia," and have successfully sought to limit some of the evidence that Durham's team had hoped to present in the two-week trial.

Last week, the judge overseeing Sussmann's case, Christopher Cooper, issued an order that will prevent Durham's team from bringing forward evidence alleging what they have described as a "joint venture" between Sussmann, representatives for Clinton's campaign and the technology executive Rodney Joffe to collect and spread opposition research about Trump.

In his ruling, Cooper said he would not oversee "a time-consuming and largely unnecessary mini-trial to determine the existence and scope of an uncharged conspiracy to develop and disseminate the Alfa Bank data."

The witness lists for both Durham's prosecutors and Sussmann's team are extensive, and include an array of current and former law enforcement and intelligence officials, former Clinton campaign operatives and a former New York Times reporter who was in touch with Sussmann around the time he met with the FBI.

In the three years since Durham was initially assigned to look into the origins of the Russia investigation, he has secured only one guilty plea of a former lawyer with the FBI who admitted to doctoring an email that was used to support a surveillance application that targeted a former Trump campaign aide.

Durham’s only other indictment outside of Sussmann was against Igor Danchenko, a lead analyst who contributed to the now-infamous Steele Dossier, who was charged last year with five counts of lying to the FBI about who his sources were for claims in the dossier. Danchenko has pleaded not guilty to all counts.

While he has conducted his investigation largely out of public view the past three years, Durham has notably opted to attend the first days of Sussmann's trial in person.