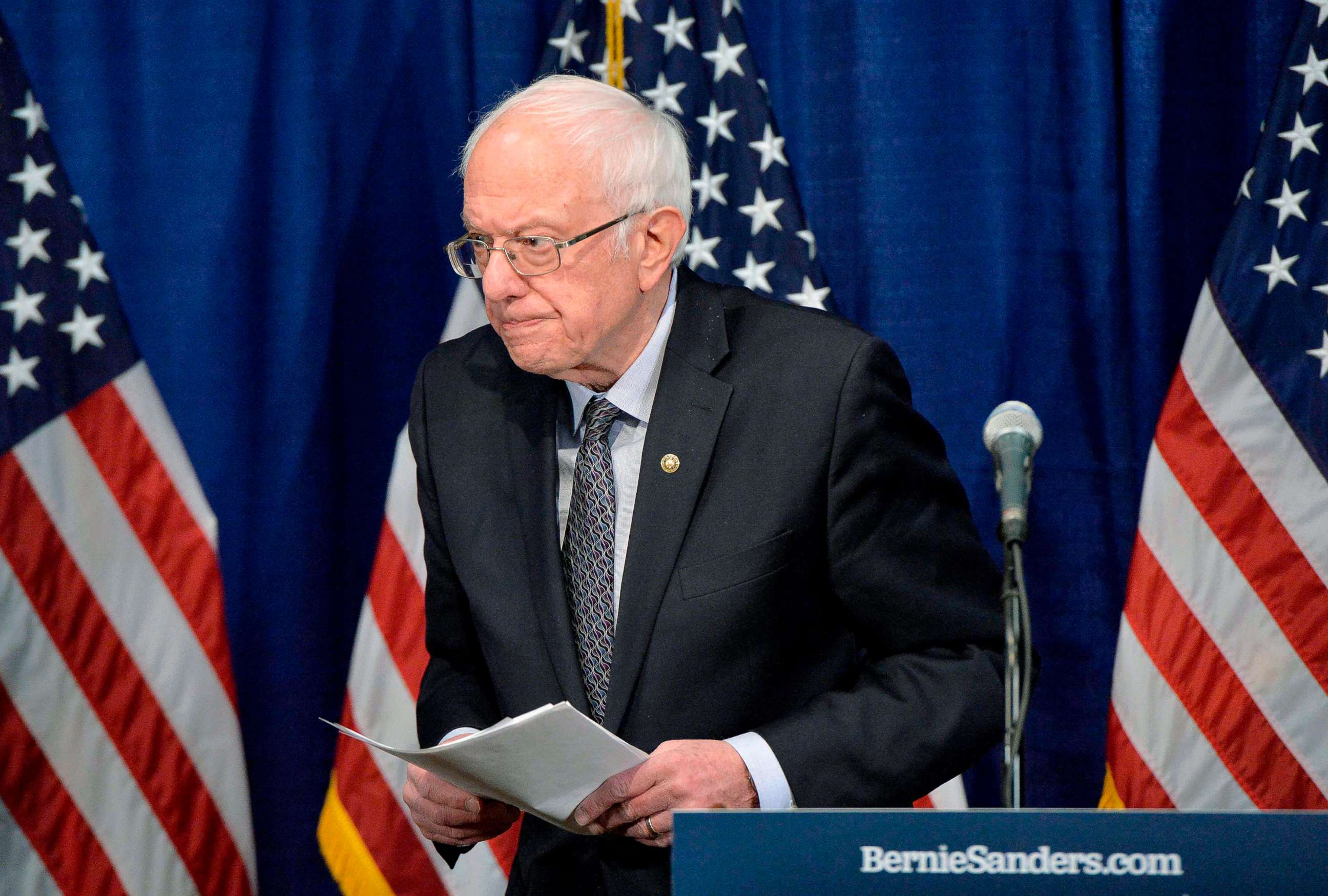

Bernie Sanders, acknowledging 'narrow path' to nomination, continues to push agenda amid pandemic

COVID-19 has provided a test case for Sanders' theory of governance.

From his home in Burlington, Vermont early Tuesday morning, in a remote interview with a comedian stationed 250 miles away, Sen. Bernie Sanders made an unusual concession.

"There is a path," Sanders, I-Vt., told Seth Meyers, when asked in an appearance on "Late Night" about his chances to win the Democratic presidential nomination, before continuing.

"It is admittedly a narrow path."

Sanders’ presidential bid exists, as with much of society's normal activities, in a coronavirus-induced holding pattern. With both the senator and former Vice President Joe Biden each suspending campaign activities, from rallies with tens of thousands of attendees down to door-to-door canvassing, and several states postponing primaries for several weeks, the opportunity for the former to claw his way back into the race, or the latter to land a final knockout punch are stuck in suspended animation.

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.

Down over 300 pledged delegates to Biden and with that "narrow path" to a spot on November's ballot appearing even steeper than the one in front of him at this point in 2016, Sanders continues to face questions about why he is choosing to remain in the race -- particularly with President Trump's approval rating ticking up slightly in recent weeks, leading many Democrats to believe that it is more important than ever for the party to unite.

"Campaigns are an important way to maintain that fight and raise public consciousness on those issues, so that's, I think, one of the arguments for going forward," Sanders said on "Late Night" as part of his same answer about continuing to campaign. It's a position that several of his staff and supporters have used to counter the unity argument, contending that his progressive platform, including his signature Medicare for All proposal, contains the solutions needed to solve many of the problems highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limited by the inability to hold rallies and with his staff stuck working at home, Sanders is instead utilizing his campaign infrastructure to promote his proposed response to the coronavirus pandemic rather than any path toward the Democratic nomination, drawing both millions of eyeballs and potential advocates for his ideas, but also criticism over his participation and engagement in the negotiations on Capitol Hill.

The campaign has mobilized its sophisticated volunteer network to call their senators to lobby for Sanders’ coronavirus-response plan, to update voters about changes to elections because of COVID-19 and to check on the well-being of fellow supporters.

Emails from Sanders campaign to supporters have been missing their typical appeal for donations to his campaign. Instead, the emails have called for recipients to read Sanders’ coronavirus response plan or have asked for help providing relief to workers impacted by COVID-19 related shutdowns and closures. The campaign released a statement last week saying it raised more than $2 million for COVID-19 relief efforts and pushed again in a solicitation Tuesday for assistance for restaurant workers, artists, tenants struggling to make rent and others affected by the pandemic.

One senior Sanders campaign official argued that its base of working-class supporters will be disproportionately affected by the economic fallout from COVID-19.

“It’s really showing that the senator and his campaign is in tune with what is happening immediately and the campaign right now is secondary to that,” said the aide.

Such efforts amid the health crisis are providing a test case for Sanders' public-driven theory of governance.

Throughout his presidential campaign, the senator pledged to be an "organizer-in-chief," and pursue his ambitious agenda by rallying the public to apply pressure on opposition leadership rather than finding compromise through drawn-out negotiations.

"When people begin to stand up and fight for policies that represent working families, no politician is going to stand in the way," Sanders explained to an audience in Anamosa, Iowa in January, adding "It's not just sitting down and arguing with Mitch McConnell, it is getting people to stand up and fight back."

Today, that position appears to be manifesting itself through live-streamed events attracting a viewership in the millions the past few weeks. Though run by his campaign, the senator has entirely avoided mention of presidential politics in favor of pitching relief proposals with help from assorted guests and supporters, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y. and international president of the Association of Flight Attendants Sara Nelson -- a platform that could potentially dwindle should his bid for the White House come to an official end.

But Sanders also faced backlash after missing a procedural vote for a coronavirus package, remaining at home in Burlington, Vermont to host a campaign-sponsored livestream focused on COVID-19 rather than return to the Capitol. A spokesperson for his Senate office later said Sanders was engaged in negotiations remotely and that they felt certain the cloture vote would fail whether or not he was present.

“If that was more than a procedural vote, Sen. Sanders would have been there,” said a campaign official familiar with the senator's thinking. “But again, he’s handling the main thing and it's no surprise that they would go reach up to criticize him.”

That criticism, coupled with questions about the impact his continued existence in the primary race may have on Democrats' chances against Trump in November, still hangs over Sanders, even as his campaign is stuck on the backburner. The vast majority of Sanders campaign staff contacted by ABC News agree with the senator that it's important he continue his run.

“Everything is so uncertain right now you’ve got coronavirus, you’ve got all of these primaries delayed, and states trying to figure out how they're going to help everybody to vote," one told ABC News.

Other allies point to the uncertainty that has existed throughout the campaign over the course of the past year as a reason to potentially stick it out.

Charles Chamberlain, chairman of progressive political action committee Democracy for America told ABC News that the response of the Democratic party establishment to Joe Biden's win in South Carolina, the subsequent coalescence of the field behind Biden, and the media coverage that came with it stalled Sanders' momentum toward the nomination, but argued it is capable of shifting again.

"I think you can say that the Sanders campaign was maybe a little flat footed by the Democratic elite response to the victory in South Carolina, but I would definitely say that, you know, he's run a very strong campaign," said Chamberlain, "But like we've seen a couple times in the campaign already, momentum can shift overnight sometimes and that's what happened with South Carolina, and that's what I think when we're looking at the race we have right now."