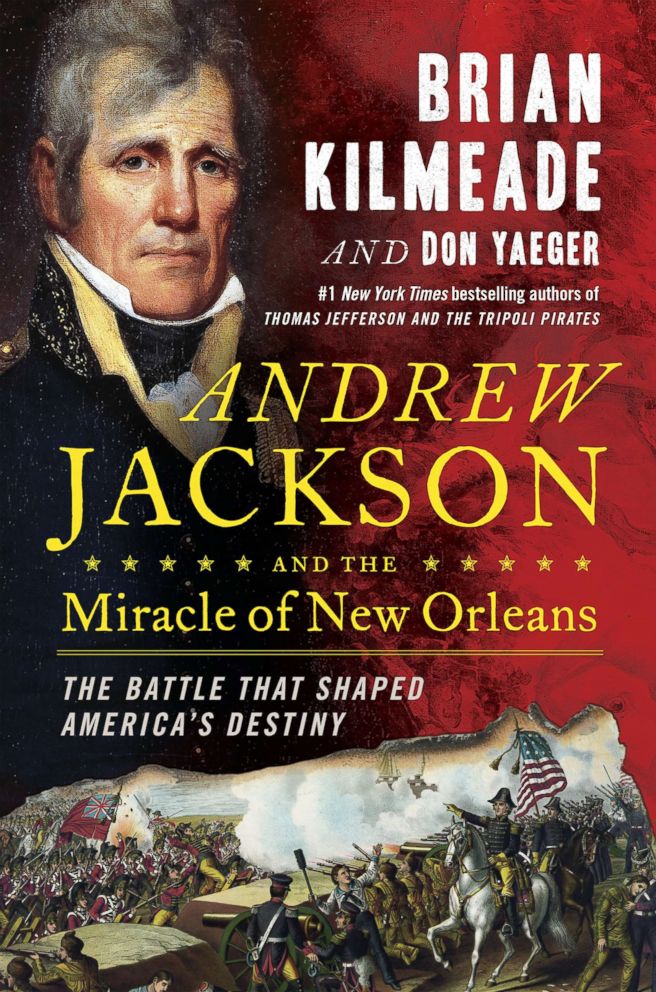

Book excerpt: 'Andrew Jackson and the Miracle of New Orleans'

Read an excerpt from Brian Kilmeade's new book.

— -- Excerpted from Andrew Jackson and the Miracle of New Orleans by Brian Kilmeade and Don Yeager, in agreement with Sentinel, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright ©2017 Brian Kilmeade and Don Yeager.

CHAPTER 1

Freedoms at Risk

These are the times which distinguish the real friend of his country from the town- meeting brawler and the sunshine patriot. . . . The former steps forth, and proclaims his readiness to march.

— Major General Andrew Jackson

On June 1, 1812, America declared war. After a hot debate, James Madison’s war resolution was passed by a vote of 19–13 in the Senate and 79–49 in the House of Representatives, and, once again, the new nation would be taking on the world’s premier military and economic power: Great Britain.

Twenty- nine years had passed since the colonists’ improbable victory in the Revolutionary War, and for twenty-nine years the British had failed to respect American sovereignty. Now, the nation James Madison led had reached the limit of its tolerance. Great Britain’s kidnapping of American sailors and stirring up of Indian tribes to attack settlers on the western frontier had made life intolerably difficult for many of America’s second generation, including those hardscrabble men and women pushing the boundaries westward.

Though reluctant to risk the new nation’s liberty, Madison was now ready to send a message to England and the world that America would stand up to the bully that chose to do her harm. The unanswered question was: Could America win? Less than thirty years removed from the last war, and with virtually no national army, were Americans prepared to take on Britain and defend themselves, this time without the help of France? The world was about to find out. In fact, so many Americans opposed the war that the declaration posed a real risk to the country’s national unity. The Federalist Party, mainly representing northerners whose economy relied on British trade, had unanimously opposed the war declaration. Many New Englanders wanted peace with Britain, and it was likely that some would even be willing to leave the Union in order to avoid a fight. Yet peaceful attempts at resolving the conflict with Britain had already been tried— and hadn’t helped the economy much. Five years earlier, when a British ship attacked the U.S. Navy’s Chesapeake, killing three sailors and taking four others from the ship to impress them into service to the Crown, then-president Thomas Jefferson had attempted to retaliate. To protest this blatant hostility, Congress passed the Embargo Act, prohibiting overseas trade with Great Britain. Unfortunately, the act hurt Americans more than the British. In just fifteen months, the embargo produced a depression that cruelly punished merchants and farmers while doing little to deter the Royal Navy’s interference and hardening New England’s resistance to conflict. Further attempts at legislative pressure in the early years of James Madison’s presidency had little effect, and British impressment had continued. By the time of the war declaration in June 1812, the number of sailors seized off the decks of American ships had risen to more than five thousand men. To many, including Andrew Jackson, then forty years old, the attack on the Chesapeake alone had been an insult to American pride that demanded a military response. As Jackson wrote to a Virginia friend after learning of the Chesapeake’s fate, “The degradation offered to our government . . . has roused every feeling of the American heart, and war with that nation is inevitable.” Yet America had waited, and the losses at sea mounted. At the same time, attempts to pacify the British had only resulted in further losses in America’s new territory, “the West,” which ran south to north from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada, bounded on the west by the Mississippi. There British agents were said to be agitating the Indians. For many years, the Five Civilized Tribes in the region (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole) had maintained peaceful relations with the European arrivals. But as more and more white settlers moved into native territories, tensions had risen and open conflict had broken out. In some places, travelers could no longer be certain whether the Native Americans they encountered were friendly; for inhabitants of the frontier, that meant the events of daily life were accompanied by fear. Stories circulated of fathers who returned from a day of hunting to find their children butchered, and of wives who stumbled upon their husbands scalped in the fields. A major Shawnee uprising in the Indiana Territory in 1811 escalated the fear. And as the bloodshed increased, there were reports that the British were providing the Indians with weapons and promising them land if they carried out violent raids against American settlers. For Andrew Jackson, the threat had become too close for comfort when, in the spring of 1812, just a hundred miles from his home, a marauding band of Creeks killed six settlers and took a woman hostage. Jackson was certain the British were behind the attack on the little settlement at the mouth of the Duck River.

Westerners like Jackson fumed at the government’s inability to resolve the country’s problems, but their clout in Washington was limited. The decision makers from Virginia and New England had little sympathy for their inland countrymen. Eastern newspapers poked fun at the hill folks’ backward ways, and much of the territory west of the Appalachian Mountains remained mysterious and wild, with few good roads and even fewer maps. The dangers faced by westerners were not felt by easterners, and their anguished demands for retaliation were scorned and dismissed by those whose wallets would be hurt by the war. But eventually, despite many politicians’ disdain for their hick neighbors to the west, Washington politics had begun to shift along with the nation’s growing population. The West had gained new influence in the elections of 1810 and 1811, when the region sent a spirited band of new representatives to the Capitol. These men saw British attitudes toward the United States as a threat to American liberty and independence; they also saw the need for westward expansion, a move that the British were trying to thwart. Led by a young Kentuckian named Henry Clay, they quickly gained the nickname War Hawks, because, despite the risks, they knew it was time to fight. Clay became Speaker of the House and he, along with the War Hawks and like- minded Republicans from the coastal states, put pressure on the Madison administration. Now, after years of resistance, Madison listened, and with Congress’s vote, the War of 1812 began. America decided to stand up for its sovereignty on the sea and its security in the West. The War Hawks in Washington were ecstatic about the declaration of war, and so was Jackson in Tennessee. At last he would have the chance to defend the nation he loved, to protect his family and friends— and, personally, to take revenge on the nation that had left him alone and scarred so many years before.

The Boy Becomes a Man

A quarter century before, Jackson had swallowed his grudge. When the Treaty of Paris made U.S. independence official in 1783, the orphaned sixteen- year- old adopted America as his family. Relatives had taken him in after his mother’s death. He became a saddler’s apprentice, then, his ambitions rising, he clerked for a North Carolina attorney. Andrew Jackson’s cobbled- together upbringing would serve him well, though he also gained a reputation as a young man who loved drinking, playing cards, and horse racing. Admitted to the bar to practice law at age twenty, a year later he accepted an appointment as a public prosecutor in North Carolina’s western district. That took him beyond the boundaries of the state, to the other side of the Appalachians. Jackson arrived in a region that, a few years after his arrival, became the state of Tennessee. The red haired, blue-eyed, and rangy six foot-one young man made an immediate impression in Nashville, a frontier outpost established just eight years earlier. As Jackson put down roots, he became one of its chief citizens as his and his city’s reputations grew. His rise gained momentum after he met Rachel Donelson, the youngest daughter of one of Nashville’s founding families. Dark- eyed Rachel was the prettiest of the Donelson sisters and full of life. It was said she was “the best story- teller, the best dancer, . . . [and] the most dashing horsewoman in the western country.” Jackson was smitten, and after she extricated herself from a marriage already gone bad, he took her as his wife. As a lawyer, a trader, and a merchant, Jackson bought and sold land. By the time Tennessee joined the Union, in 1796, he had won the respect of his neighbors, who chose him as their delegate to the state’s constitutional convention. Jackson then served as Tennessee’s first congressman for one session before becoming a U.S. senator. But he found life in the political realm of the Federal City frustrating— too little got done for the decisive young Jackson—and he accepted an appointment to Tennessee’s Supreme Court. In the early years of the nineteenth century, he divided his energies between administering the law and establishing himself at his growing plantation, the Hermitage, ten miles outside Nashville. “His house was the seat of hospitality,” wrote a young officer friend, “the resort of friends and acquaintances, and of all strangers visiting the state.” His next venture into public service would suit him better: thanks to his strong relationships and sound political instincts, he was elected major general of the Tennessee militia, in February 1802. Maintained by the state, not the federal government, the militia was provisioned by local men who supplied their own weapons and uniforms and served short contracts of a few months’ duration. Leading the militia was a good fit for Jackson’s style, because it gave him the chance to serve the people he loved with the freedom he needed and the challenge he craved. General Jackson repeatedly won reelection as well as the deep loyalty of his men. They liked what he said. He was often outspoken, and many shared his uncompromising views on defending settlers’ rights. With rumors of war, he was ready to defend his people and was just the man to rally westerners to the cause of American liberty. “Citizens!” he wrote in a broadside. “Your government has at last yielded to the impulse of a nation. . . . Are we the titled slaves of George the Third? The military conscripts of Napoleon the great? Or the frozen peasants of the Russian czar? No— we are the free-born sons of America; the citizens of the only republic now existing in the world.” Jackson understood the stakes of the war, and he recognized the strategy as only a westerner could. Of critical importance to victory in the West was a port city near the Gulf Coast. As Jackson would soon say to his troops, in the autumn of 1812, “Every man of the western country turns his eyes intuitively upon the mouth of the Mississippi.” Together, he observed, “[we are] committed by nature herself [to] the defense of the lower Mississippi and the city of New Orleans.”

The City of New Orleans

New Orleans was important—so important, in fact, that upon becoming president a dozen years earlier, Thomas Jefferson had made acquiring it a key objective. Recognizing the city’s singular strategic importance to his young nation, he wrote, “There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans.” Knowing that Napoleon’s plan for extending his American empire had suffered a major setback in the Caribbean, where his expeditionary force had been decimated by yellow fever, Jefferson sensed an opportunity. He dispatched his friend James Monroe to Paris, instructing him to try to purchase New Orleans.

Monroe had succeeded in his assignment beyond Jefferson’s wildest dreams. Recognizing his resources were already overextended in his quest to dominate Europe, Napoleon agreed to sell all of Louisiana. That conveyed an immense wilderness to the United States, effectively doubling the size of the new country. The Louisiana Purchase had been completed in 1803 and, at a purchase price of $15 million for more than eight hundred thousand square miles of territory, the land had been a staggering bargain (the cost to America’s treasury worked out to less than three cents an acre). The Louisiana city of New Orleans was the great gateway to and from the heart of the country. America’s inland waterways— the Ohio, the Missouri, and the numerous other rivers that emptied into the Mississippi—amounted to an economic lifeline for farmers, trappers, and lumbermen upstream. On these waters flatboats and keelboats were a common sight, carrying manufactured goods from Pennsylvania, as well as crops, pelts, and logs from the burgeoning farms and lush forests across the Ohio Valley, Cumberland Gap, and Great Smoky Mountains. On reaching the wharves, warehouses, and quays of New Orleans, the goods went aboard waiting ships to be transported all over the world. Although Louisiana became a state in April 1812, the British still questioned the legitimacy of America’s ownership of the Louisiana Territory—Napoleon had taken Louisiana from Spain and, to some Europeans, it remained rightfully a possession of the Spanish Crown. Jackson feared that sort of thinking could provide the British with just the pretext they needed to interfere with the American experiment—capturing New Orleans would be the perfect way to disrupt America’s western expansion. Now that America had finally gone to war, many nagging practical questions hung in the air in Washington. Who would determine America’s military strategy? Who would lead the nation to war? The generals of the revolutionary generation were aging or dead. The passing of George Washington had sent the nation into mourning thirteen years before, and no military leader had the stature to take the general’s place. Although the country had prevailed in the previous decade in a war on the Barbary Coast of North Africa, defeating pirate states that had attacked its shipping and held its men hostage, this was a bigger fight for even bigger stakes. Although neither Mr. Madison nor the members of Congress could know it in June 1812, the burden of protecting the West would eventually settle onto the narrow but resilient shoulders of General Andrew Jackson, a man little known and less liked outside his region. But first Jackson had to convince the men in Washington that a general from the backwoods was the one to lead the fight. That would be anything but easy.