COVID-19 test access disparities in some south Florida communities fall along racial, socioeconomic lines: ANALYSIS

Long lines cause other problems too.

Martin Torres waited seven hours in line for a COVID-19 test at Hard Rock Stadium, an open-air venue best known as the home of the Miami Dolphins, while showing what he believed to be symptoms of the virus. When he finally reached the front, he was told he’d get results back in five days.

Two weeks later, he is still waiting.

“I am kind of in a limbo waiting for when I can have a response for that,” Torres said. “It's important.”

In a statement responding to the demand in testing and the slower turnaround times, Quest Diagnostics, one of the major labs processing COVID-19 tests, said it will “continue to ramp up capacity to reach 150,000 molecular diagnostic tests a day."

Florida, where the pandemic has recently spiked to nearly 370,000 confirmed cases, expanded testing capacity in response to problems surrounding testing access equity. But being a resident of a lower-income neighborhood still presents a challenge in terms of getting a COVID-19 test.

According to a new, extensive review of testing sites by ABC News, FiveThirtyEight and ABC-owned television stations, sites in communities of color in many major cities face higher demand than sites in whiter or wealthier areas in those same cities. The result of this disparity is clear: People of color, especially Blacks and Latinos, are more likely to experience longer wait times and understaffed testing centers.

This nationwide review is one of the first to look at testing site locations coast to coast, in all 50 states plus Washington, D.C., using data provided by the health care navigation company Castlight Health (the same data that Google Maps uses to surface COVID-19 testing sites). An assessment of city and state health department websites also revealed, over and over, fewer testing sites in areas primarily inhabited by racial minorities.

Importantly, our analysis does not factor in the capacity of testing sites -- which can vary from just 50 tests at one site to 2,000 at another, meaning that one site might be equipped to serve a larger number of people than another site. Instead, it looks at the potential demand for each site based on the number of people and sites nearby. The data we used also is less likely to reflect tests done in private physicians’ offices than federally-funded community sites, local government-run mobile pop-up sites, urgent care clinics and hospitals. The analysis also doesn’t take into account other factors that could determine testing accessibility, such as staffing and wait times, as well as other restrictions on testing like appointment or insurance requirements.

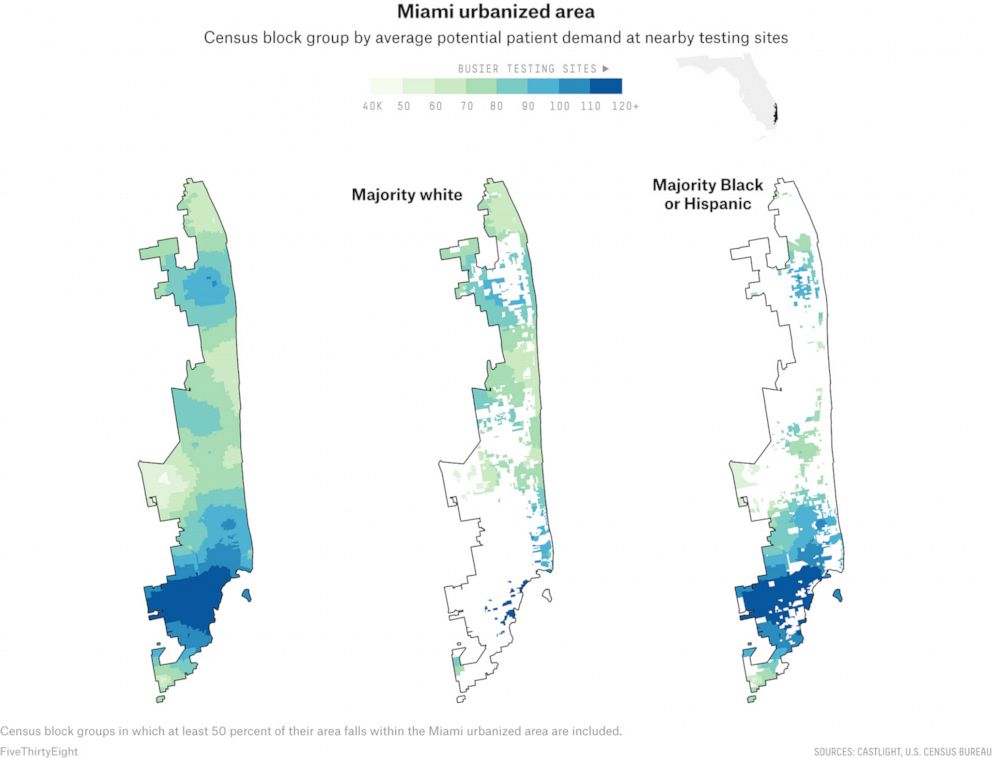

The South Florida region, which the Census refers to as the Miami urbanized area, contains at least part of Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties, and has deep disparities in testing site availability in majority-Black neighborhoods, majority-Hispanic neighborhoods and majority-white neighborhoods, according to our analysis.

The neighborhoods included in the Miami urbanized area have massive economic inequality, and disparities exist within different Hispanic communities. Yet the few testing sites in wealthy areas — such as Cooper City, a majority-white town located in Broward County just north of Miami-Dade — had a much smaller potential patient demand than sites in many of the more densely populated lower-income neighborhoods, many of which are majority-Black and majority-Hispanic.

On average, majority-Black areas had a potential community need 13 percent larger than majority-white census blocks. In majority-Hispanic areas, it was 29 percent larger, with the densely populated, predominantly Hispanic areas around South Miami showing a particularly high potential need.

Just 10 miles south of Cooper City is Miami Gardens, a predominantly Black area in Miami-Dade County where the median household income is less than half that of Cooper City. If residents there want to get a test, they have to travel to Hard Rock Stadium and wait in a line that officials have advised could be as long as four hours in the summer heat that sometimes nears 100 degrees.

The long lines cause other problems too. On most days at the Hard Rock Stadium testing site, it is not uncommon for testing to temporarily pause due to lightning in the area or because a car waiting in line breaks down due to mechanical issues.

"We have seen cars run out of gas at some of the busier test sites, but we tell people that a little bit of planning and a lot of patience are required,” said Mike Jachals, a state spokesman for several of the federally-supported testing sites across the state.

In an emailed statement to ABC News and FiveThirtyEight, a state emergency management spokesman said Florida “is continuing to increase COVID-19 testing daily.”

A spokesman for Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos Gimenez said the county has made “a concerted effort” to put more testing facilities in lower-income communities throughout the county. As part of that effort, new pop-up sites at the Joseph Caleb Center in central Miami and Harris Field Park in south Miami-Dade, both located in predominantly Black or Hispanic areas, have been installed.

In Miramar, a city of about 140,000 just north of the Hard Rock Stadium, there’s only one public COVID-19 testing center even though it happens to be the city with one of the largest percentages of Black people in Broward County. The city received the state funding necessary to open its first state-supported testing site just over a month ago, which local officials believe was far too late.

“Initially, I was very concerned, very upset,” said Miramar Mayor Wayne Messam in response to a question about the lack of urgency in establishing testing facilities in the city. “It was very disappointing and upsetting, but I was actually happy once we did get the call notifying me that we would have the site and since that determination was made, we’ve made the best of that site. It would have been ideal to have it up since the onset.”

Laura Bronner is FiveThirtyEight's quantitative editor

Grace Manthey, a data journalist for ABC Owned Television Stations in Los Angeles, ABC News’ Briana Stewart and FiveThirtyEight’s Rachael Dottle contributed reporting.