Crunch time for voter ID clinics as states tighten election laws

Millions lack valid government ID to access social services and vote.

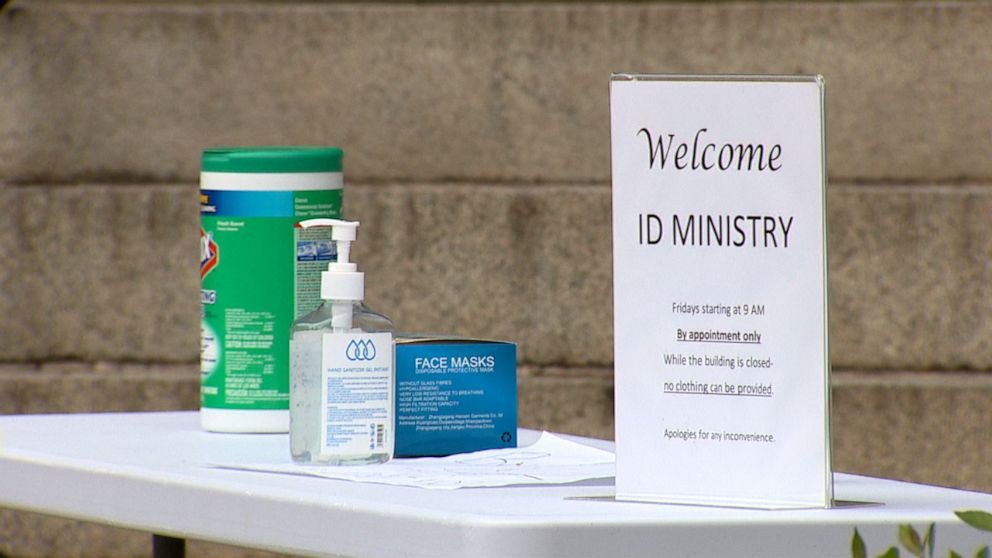

For more than 20 years, Americans from all walks of life have been lining up outside Foundry Methodist Church -- just blocks from the White House -- seeking help proving to the government they are who they say they are.

"I tried, but they said you have to have documentation," said Connie Folk, who was accompanying her older brother Morris Cole to an appointment with the church's ID ministry. "I don't know how to do this."

The complicated and costly maze of paperwork and online portals leading to official government identification, like a drivers license or state ID card, has taken on fresh urgency in the pandemic and as more states move to require official ID for casting a ballot.

Wyoming this month became the 36th state to mandate ID for in-person voting. Last month, Georgia joined the list of 10 states requiring proof of ID to apply for a ballot to vote by mail.

"Any time you place a requirement to produce ID, it's going to be a barrier for folks who have to go through the process," said the Rev. Ben Roberts who oversees Foundry's ID ministry, which has helped thousands of people successfully apply for identification over the years.

Even though the next election is months away, voter advocates are ramping up their efforts to help the ID-less, citing lengthy processing delays during the pandemic and because valid identification is necessary before an individual can even register to vote.

"The timing could not be more critical," said Kathleen Unger, founder of VoteRiders, a nonpartisan advocacy group helping to close the ID gap nationwide. "When it comes to voter ID, procrastination is not your friend."

Cole, whose state ID expired years ago, said he has been unable to apply for housing assistance and food stamps. In his home state of Virginia, he is also unable to vote without valid photo ID.

"If you don't have regular access to a computer, if you don't have a credit card, those are almost insurmountable obstacles to obtaining ID," said Lisa Holmstead, a Foundry volunteer helping Cole. "And especially currently, you cannot go in person to obtain a birth certificate."

An estimated 21 million Americans, or 11% of all adults, don't have valid government identification, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan voter advocacy group.

"We know life circumstances happen," Roberts said. "Items get thrown away, or wet or destroyed. People lose them in evictions. People might lose them in a fire or something like that. But the most common thing that we see is they just get destroyed or lost."

Small armies of nonprofit volunteers are staffing ID clinics in dozens of states this spring. The nonpartisan advocacy group Spread the Vote is prioritizing efforts in North Carolina, Florida, Wisconsin, Texas and Georgia, where lawmakers last month enacted a new ID requirement for mail-in ballots. More than 600 Americans have been helped since last fall.

"We know from the mouths of the people who are trying to get these laws passed that there is a reason that they're doing it. And it's not about voter fraud," said Kat Calvin, founder and executive director of Spread the Vote. "Every reputable study has found that we've had point zero, zero, zero, zero, zero, zero nine percent, right, like fraud at the polls. We just -- it doesn't happen."

Many state officials of both parties argue that proof of a voter's identity and eligibility should be a basic prerequisite for voting.

"When voting in person in the state of Georgia you must have a photo ID. It only makes sense for the same standard to apply to absentee ballots as well," Georgia Gov. Brain Kemp, a Republican, said last month.

But critics of the stricter ID laws call them a requirement that excludes. The average cost of a government ID is $40, according to advocates. Add in the price of obtaining the underlying documents -- like a certified birth certificate -- and some see a modern day poll tax.

"I think it is hard to reach any other conclusion other than the fact that there are some politicians who want to manipulate the rules of the game so that some people can participate and some people can't," said Myrna Perez, an election law expert with the Brennan Center for Justice.

For years, some Republicans have openly boasted about using voter ID requirements to gain a political edge.

"Now we have photo ID (law), and now I think photo ID is gonna make a little bit of a difference as well," Rep. Glenn Grothman, R-Wis., told a local news reporter about why Republicans would have electoral success in the state in 2016.

North Carolina GOP activist Don Yelton was forced to resign in 2013 after controversial comments on The Daily Show about his state's voter ID law. "If it hurts a bunch of college kids as too lazy to get up off their bohunkus and go get a photo ID, so be it," he said.

In 2012, Pennsylvania House Republican Leader Mike Turzai predicted that a new state voter ID requirement "is gonna allow (Republican presidential nominee) Gov. (Mitt) Romney to win the state of Pennsylvania -- done."

Democratic President Barack Obama ultimately won Pennsylvania and a second term in 2012.

The National Bureau of Economic Research looked at more than a decade of voting trends and concluded that state ID laws had "no negative effect on registration or turnout, overall or for any group defined by race, gender, age, or party affiliation."

"In essence, they're saying there's just no evidence that it keeps people out of the polls," said Hans von Spakovsky, a senior fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank. "Turnout, including of Black and Hispanic voters, has increased greatly."

A 2005 national bipartisan election reform commission co-led by former President Jimmy Carter even said ID laws were a good idea.

"It will not restrict people from voting. It will be uniformly applied throughout the country, and it will be nondiscriminatory," Carter said of the commission's recommendation for a national voter ID standard.

Such a policy has never been adopted, and nonpartisan voter advocates say a patchwork of state ID laws remains inherently discriminatory.

"Who doesn't have a driver's license? Poor people, communities of color, people who are in communities that have lower incidence of car ownership, which are lower or lower income communities and communities of color," said Alex Gulotta, an Arizona voting rights advocate with the group All Voting Is Local.

Some researchers also say there's no evidence that voter ID laws have an effect on fraud -- actual or perceived -- emboldening skeptics of stricter rules, even in states like Georgia that offer voter ID for free.

"The free voter ID is only good for voting," said Kat Cavlin, founder of Spread the Vote. "But when you don't know where you're going to sleep at night or how you're going to feed your children, or whether or not you can get a job without going through all of those hoops to get an ID that's only going to help you with something once a year, is not something that most people have the capacity to do."

Von Spakovsky of the Heritage Foundation, which supports voter ID requirements and the new Georgia election reform law, said even without valid identification many indigent Americans can still exercise their rights.

"If you don't have a Georgia ID, including the free ID that the state will give you, you can instead provide a photocopy of a utility bill, bank statement, paycheck or government document with your name and address on it," he said. "I don't know how anybody could possibly say that is somehow a 'Jim Crow requirement.' It's easily met."

Most Americans support voter ID laws. In Georgia, the support appears even stronger, according to recent polling. A February survey conducted by the Atlanta Journal Constitution found 74% back the new state rules for proof of ID to vote by mail.

"When you simply require a voter, for example to write in the serial number of their state voter ID card, you don't have to worry about signature comparison," von Spakovsky said.

Still, voting rights advocates say ID requirements are only getting increasingly tough to navigate, leaving volunteers and families in a sprint to close the ID gap.

"Since September, we've helped 700 people," said Holmstead, the Foundry volunteer. "That's just a drop in the bucket. And we have people waiting and waiting for our appointments. We can only do so much, you know."