Crying for Clemency: A Life Sentence for Drugs

A convicted teenage drug lookout will die in prison without clemency.

— -- As thousands of federal inmates are readied for early release as part of a national drug sentencing overhaul, Ronald Evans can only continue to dream from behind bars.

The 41-year-old non-violent drug offender has served more than two decades for a crime he committed before he was even an adult. Under the mandatory minimum sentencing rules in place when he was convicted, Evans is slated to serve his entire lifetime.

"I had committed a very big and serious definite mistake," Evans told ABC News in an interview over email from inside Petersburg Medium Security Correctional Facility in Hopewell, Virginia. "I always wish I had taken 'The Other Road.'"

Evans was just 15 years old, living with his mother in public housing in Norfolk, Virginia, when his troubles began. He lived in a neighborhood riddled with crime and rampant drug use, falling in with the wrong crowd. When some older boys he knew offered him $50 a day to function as a "look-out" for their drug retailing operation, it seemed like easy money.

"That was what everyone my age and older was doing,” Evans said. Based on what he saw in his neighborhood, he believed at the time "there was nothing wrong with it."

The "it" was taking part in an illicit and dangerous business that pumped heroin into the streets. Within a couple of years, Evans had moved into transporting money and drugs, actively selling heroin to addicted buyers, he said.

By the time federal agents broke up the drug ring, Evans was still a minor. Others were arrested, but initially he was not. In August 1992, just after his 18th birthday, authorities swooped in to detain Evans and charge him with conspiracy and possession with intent to distribute.

With no drugs and no weapons in his possession, the government used only the testimony from his co-defendants to hold him accountable for large amounts of heroin, cocaine, and crack in the streets. A judge agreed.

When it came time for sentencing, the outcome for Evans was a shock: life in prison, with no possibility of parole.

“When I first got the sentence I didn’t even know what it really meant,” he says. “I was so young at the time. I just didn’t know any better.”

Despite the fact that he was arrested as an adult, Evans' prison term was dictated by guidelines requiring the judge to consider his three non-violent juvenile offenses in addition to his new drug conviction.

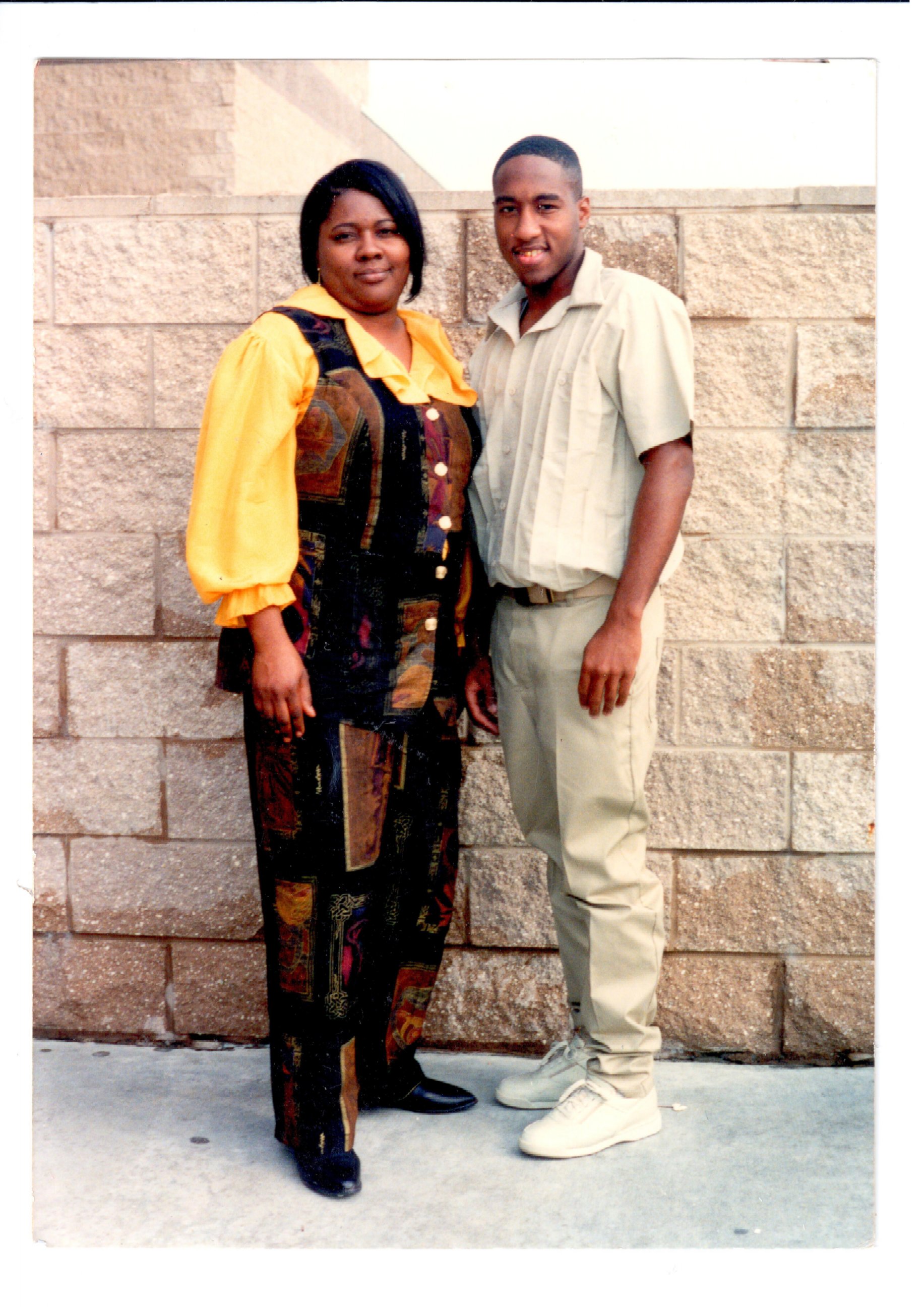

In 1993, at age 19, Ronald Evans was sent to federal prison where he's spent the last 22 years. Without a presidential commutation of his sentence, or legislative action to reduce sentences like his, he may eventually die there.

The Obama administration and a bipartisan coalition in Congress are studying cases like Evans' and ways to overhaul sentencing guidelines and apply reduced terms to some already-imprisoned convicts. One federal initiative could impose shortened sentences in the next few years to as many as 40,000 inmates. The president himself has also personally commuted dozens of sentences for individuals who have appealed directly to him.

"I wish he could be released," Evans' mother Janice said through tears of concern. She was 35 years old when Ronald, her only son, was arrested. "I worry about him so much, every day." Ronald is not the only one doing time for this crime, she says.

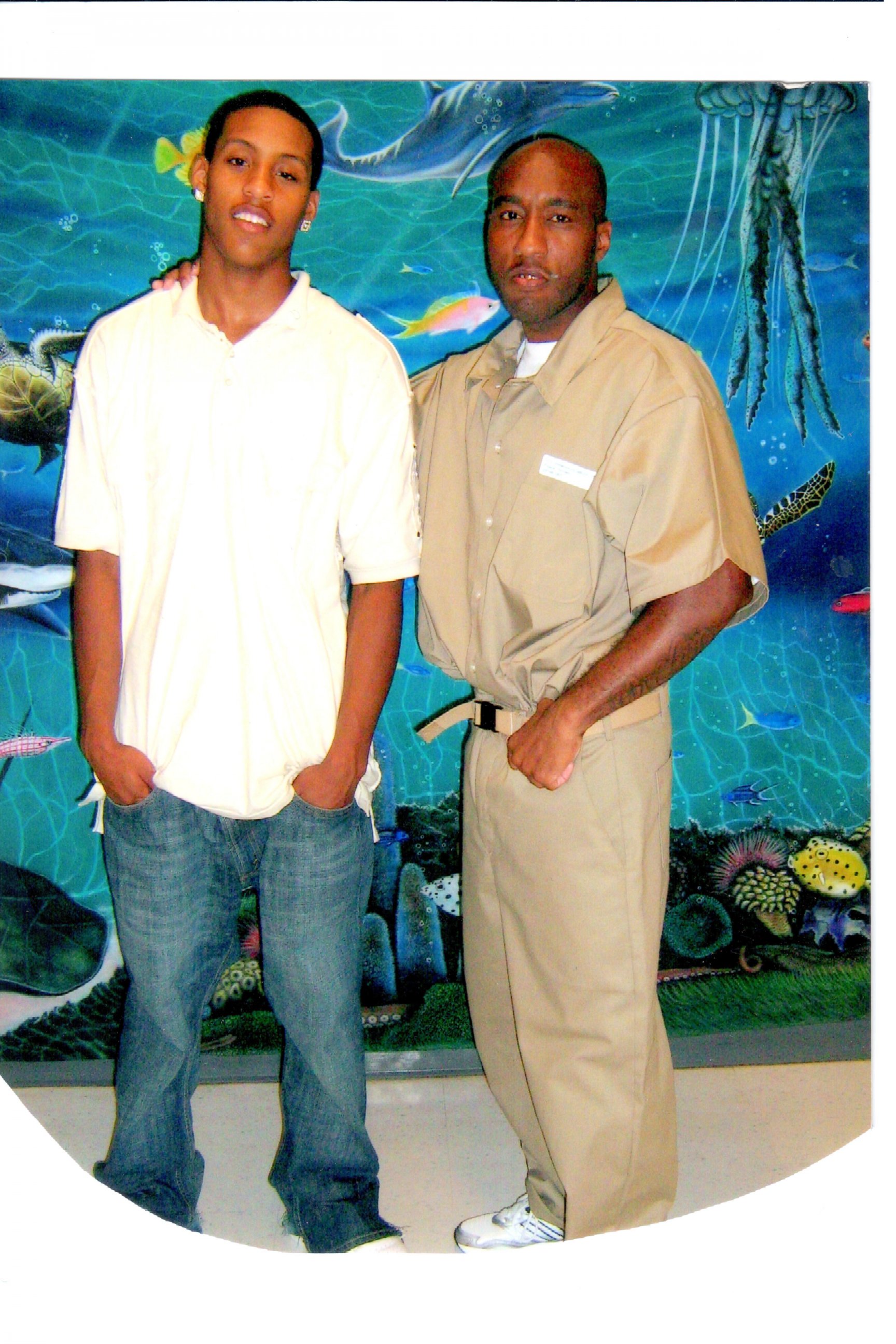

A third person’s life is also caught up in this sentence.

A few months before he was sent away, Ronald’s son, D’Ron Harrison, was born. Now 23 years old, D’Ron has never known his father outside the razor wire confinement of a federal prison.

"Everyone needs, deserves, and should be accorded a second chance at life," Ronald Evans told ABC News. "I only hope and pray that one day, just one day, someone can accord me enough trust, and have an ounce of faith in me, to see the sincerity that is within me now and for all time."