The day that changed politics, 4 years ago today

ABC News Chief White House Correspondent Jonathan Karl on Oct. 7, 2016.

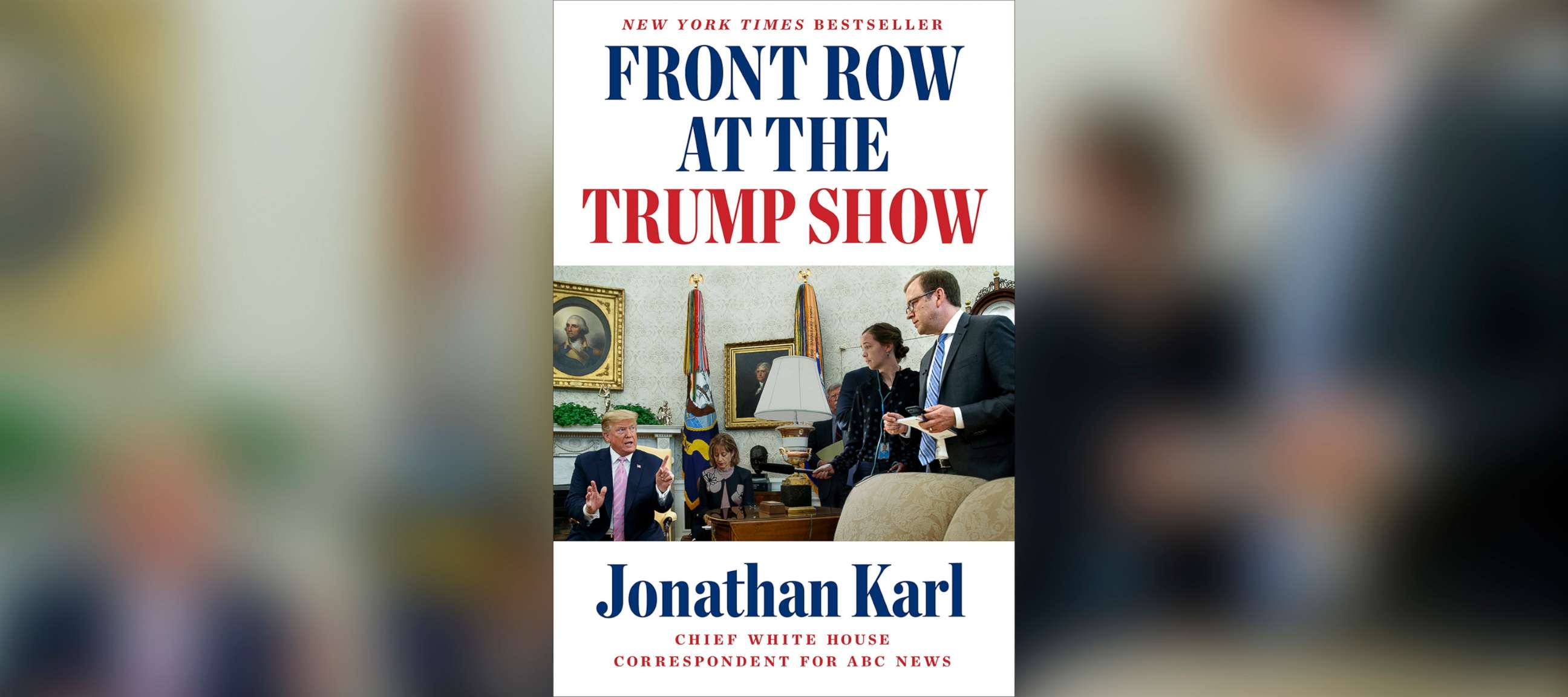

Today is the four-year anniversary of the single most consequential day of the 2016 presidential campaign and perhaps of any presidential campaign in memory. It also happens to be Vladimir Putin's birthday. In "Front Row at the Trump Show," I detailed what was happening behind the scenes on the day almost everybody thought the Trump era was over, but it was really just beginning.Here's an excerpt.

-- ABC News Chief White House Correspondent Jonathan Karl

CHAPTER FIVE

FOUR HUNDRED FIFTY ROSES

On Friday, October 7, 2016, Vladimir Putin received a massive bouquet of four hundred fifty roses—a gift for his sixty-fourth birthday, one rose from each member of the Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament.

“Let’s send him the bouquet with gratitude for his hard work and with our promise that we will all work with him for the benefit of our great Russia,” proclaimed lawmaker Valentina Tereshkova.

Back in the United States, dawn was breaking on the most consequential day yet of the Trump era, a day when just about everybody assumed it was all over, but it was really just beginning.

News coverage that morning was dominated by Hurricane Matthew, a Category 5 storm that had already torn through Haiti and was moving up the east coast of Florida. Several conservative commentators, including radio host Rush Limbaugh, claimed media accounts were exaggerating the storm to scare people about the threat of climate change. In Washington that morning, Secretary of State John Kerry issued a blistering statement accusing Russia of aiding Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad’s attacks on civilians in the city of Aleppo.

“These are acts that beg for an appropriate investigation of war crimes,” Kerry said. “And those who commit these would and should be held accountable for these actions.”

As for the campaign, it appeared to be a quiet day. With the second of three planned Clinton/ Trump debates just two days away, both candidates were taking a break from the campaign trail, huddling with aides and preparing. Hillary Clinton was at the Doral Arrowwood resort, not far from her home in Chappaqua, New York, doing practice debates, complete with a replica of the stage that would be used Sunday night in the town- hall- style debate to be moderated by my ABC colleague Martha Raddatz and CNN’s Anderson Cooper. Philippe Reines, Clinton’s combative communications advisor with a reputation for browbeating reporters with profanity- laced diatribes, played the part of Donald Trump. There were no mock debates for the Trump campaign, but even the famously practice- averse Donald Trump spent much of the day huddled with his top advisors— including Steve Bannon, Jared Kushner, David Bossie, Kellyanne Conway, Chris Christie, and Reince Priebus— tossing around possible debate questions and answers in a conference room on the twenty-fifth floor of Trump Tower.

Shortly after noon, Hope Hicks received a media inquiry that would throw the presidential race into chaos and dominate news coverage for the final stretch of the campaign— and a story that, in hindsight, was actually only the third- most important development of the day in terms of the lasting impact on the race and the nation.

David Fahrenthold of The Washington Post, a quirky and dogged reporter who made a name for himself (and eventually earned a Pulitzer Prize) with his relentless reporting on the Trump Foundation and Trump’s dubious claims of charitable giving, told Hicks he had obtained a video outtake from an interview Trump had done with Billy Bush on the TV program Access Hollywood in 2005. Hicks had dealt with countless Trump controversies over the course of the campaign, but she knew this one was different. Here was Donald Trump on tape bragging about his ability to sexually assault women because of his fame. The transcript of the tape was horrific.

“You know, I’m automatically attracted to beautiful [women]— I just start kissing them,” he is heard telling Billy Bush. “I don’t even wait. And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything.”

Hicks pulled Conway, Bossie, and Bannon out of the debate prep session and showed them the transcript. Then she called Kushner out. Eventually the only people left with Trump in the conference room were Christie and Priebus.

“Where the hell did everybody go?” Trump asked. “I don’t know,” Christie responded, “but whenever all my staff left the room without telling me, it was never good news.”

Trump yelled for everybody to come back into the conference room, and as they did, Hicks handed him the transcript.

“This doesn’t sound like me,” Trump said as he started reading it. They decided to have the campaign’s lawyer, Don McGahn, call The Washington Post and demand to see the actual tape. Trump told Kushner to get an audio expert ready to review it and expose it as a fake. Fahrenthold sent over the actual video and Hicks played it for the group on her laptop computer. After listening for less than thirty seconds, Trump looked up: “Oh, yes. It’s me.”

The campaign now faced an existential crisis.

While Trump and his advisors debated how to respond— and before The Washington Post published the story and released the tape for the rest of the world to hear— there was another story developing in Washington.

At three p.m., the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence released a joint statement placing blame on the Russian government for the recent hacks of the Democratic National Committee’s emails and the public release of those emails on WikiLeaks. The release of those emails had been timed to do maximum damage. WikiLeaks had started posting them just as the Democratic National Convention was getting under way. There had been suspicions that Russia was behind the hacks, but this was an official statement by US intelligence placing the blame not just on “Russians” but “the Russian government.” And the statement made two other allegations: 1) The theft and public release of these emails was intended to interfere with the presidential election, and 2) “Only Russia’s senior- most officials could have authorized these activities.” In other words, Putin himself was trying to interfere with the US presidential election.

The statement on Russian interference immediately generated big headlines and breaking-news coverage on the cable news channels. The Obama White House was getting requests from reporters for briefings for more information on these explosive allegations.

But the frenzy of interest subsided an hour later, when David Fahrenthold’s story— along with the incriminating video— was posted on WashingtonPost.com.

The story of the Access Hollywood video immediately overtook the story about Russian interference. At the White House, Communications Director Jen Psaki and others on her staff watched the Access Hollywood story unfold and assumed the presidential race was now over. The idea of putting together briefings for reporters on Russian interference suddenly seemed less urgent. Several members of the White House communications staff went out for drinks— an early Friday happy hour.

As soon as the story hit the Washington Post website, Hillary Clinton’s mock debate at the Doral Arrowwood resort came to a screeching halt as her top aides gathered around to watch the video on the laptop of Bob Barnett, the Washington superlawyer and longtime friend of the Clintons.

“We thought this was a death blow to Trump,” Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta later told me.

But Podesta was about to find out there was more to come. At four thirty p.m.— less than a half hour after The Washington Post published the Access Hollywood video— Podesta got a call from Clinton campaign headquarters in Brooklyn. It was the campaign’s deputy press secretary, Glen Caplin. He had devastating news. WikiLeaks was back at it, Caplin told him. They had just released another cache of Democratic emails: Podesta’s emails. This time the Russian hackers had drawn blood from the Clinton campaign and Podesta himself. They had no way to know how many emails had been stolen, so Podesta gave Caplin the green light to look through his entire personal email account. And with that, the team of people at Clinton campaign headquarters started going through the thousands of emails in Podesta’s personal email inbox. Any message, no matter how private, could be made public. The campaign needed to know exactly what was there.

The timing of all this is astounding on multiple levels.

Consider all that had just happened in the space of ninety minutes. At three p.m., US intelligence tells the world that the Russian government, at the highest levels, was behind an effort to undermine the presidential election. A few minutes after four p.m., The Washington Post publishes the Access Hollywood video. Less than thirty minutes after that, WikiLeaks begins publishing the most damaging set of stolen emails yet.

The release of the Podesta emails may have been the most seismic story of all. Their release showed that the brazen attempt of the Russian government to mess with a US presidential election was continuing even as the US government was calling it out.

Conservative outlets, including the Daily Caller and the Drudge Report, were the first to jump on the leaked Podesta emails. ABC News made a decision not to quote the emails in our broadcasts or online. For one thing, we could not confirm their authenticity, and even if they were real, we couldn’t guarantee that none of them had been doctored. Furthermore, they were stolen property.

But several other mainstream news organizations charged ahead, publishing stories within hours that quoted liberally from the pilfered emails. The headline in the New York Times story that was posted early that evening read, “Leaked Speech Excerpts Show a Hillary Clinton at Ease with Wall Street”— but these weren’t “leaked” emails. They were stolen. Stolen by the Russians, no less.

“In lucrative paid speeches that Hillary Clinton delivered to elite financial firms but refused to disclose to the public,” the Times story began, “she displayed an easy comfort with titans of business, embraced unfettered international trade and praised a budget- balancing plan that would have required cuts to Social Security, according to documents posted online Friday by WikiLeaks.”

NBC News ran a story that day quoting the emails, saying, “Their release contains quotes likely to create new headaches for Clinton on both her left and right flanks just ahead of Sunday’s second presidential debate.”

Neither story made any reference to Russia’s campaign to interfere with the election, a campaign that US intelligence had just said featured the theft and distribution of Democratic Party emails.

But at that point, the story dominating news coverage in the United States was the Access Hollywood tape. Aside from a few print and online stories about Podesta’s emails that were damaging to Hillary Clinton, the political news was wall- to- wall coverage of the tape.

Back in Trump Tower, nearly an hour after the Access Hollywood tape was posted, the Trump campaign finally released a written statement. It was short— and defiant: “This was locker-room banter, a private conversation that took place many years ago. Bill Clinton said far worse to me on the golf course— not even close. I apologize if anyone was offended.”

The statement only made matters worse. Republican leaders, who had never liked Trump in the first place, started running from him.

Reince Priebus left New York with Senator Jeff Sessions and RNC officials Mike Ambrosini and Alex Angelson aboard the six p.m. Amtrak Acela train to Washington. Throughout the three- hour train ride, Priebus was on the phone taking calls from Republican leaders of all stripes outraged by the Access Hollywood tape and what it meant for the campaign.

Priebus heard from Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and several other Republican senators. He heard from top Republican donors. He heard from local Republican leaders and from several of the 168 elected members of the Republican National Committee. In an effort to find some privacy on the crowded train, Priebus got up from his seat as it pulled out of New York and stood outside the bathroom by the doors of the train that open onto the platform. He stayed there for the duration of the trip.

House Speaker Paul Ryan called Priebus several times. So did Wisconsin governor Scott Walker. Trump was scheduled to appear with both of them the following day at an event in Wisconsin. They wanted to disinvite him. Priebus asked them to hold off and give him time to talk Trump into canceling the trip on his own, so it wouldn’t look like he was so radioactive that the Speaker of the House refused to share a stage with him, which was, of course, exactly what was happening. Walker also sent Christie a text with a blunt message: The election is over.

Before Priebus could get Trump to cancel the Wisconsin trip on his own, Ryan put out a statement disinviting the Republican presidential nominee from the Wisconsin event: “I am sickened by what I heard today. Women are to be championed and revered, not objectified.” Priebus felt blindsided by his old friend and political mentor. The whole situation was spiraling out of control.

Trump’s vanquished Republican opponents piled on too. Jeb Bush was among the first to publicly call Trump’s behavior inexcusable: “I find that no apology can excuse away Donald Trump’s reprehensible comments degrading women.” And, a little later, Ted Cruz: “These comments are disturbing and inappropriate, there is simply no excuse for them.”

Eventually, even Donald Trump saw how dire his situation was. At about midnight, he put out a video statement that included an actual apology: “I said it, it was wrong, and I apologize.”

For candidate Trump it was a first: an unequivocal apology. No parsing, no hedging. He acknowledged the voice on the tape was his, he owned it, and he apologized.

Trump being Trump, he also added a shot at Hillary Clinton and her husband.

“Hillary Clinton, and her kind, have run our country into the ground. I’ve said some foolish things, but there is a big difference between words and actions. Bill Clinton has actually abused women and Hillary has bullied, attacked, shamed, and intimidated his victims.”

And he closed the video statement by telegraphing that not only was he not dropping out of the race, he was ready to go on the attack against the Clintons: “We will discuss this more in the coming days. See you at the debate on Sunday.”

On Saturday morning, the top political story on the front pages of The New York Times and The Washington Post was the Access Hollywood tape. The intelligence community’s revelation about Russian election meddling was a secondary story. The Post also had a front- page story delving into Podesta’s emails— a story that detailed damaging information about private speeches Hillary Clinton had given to groups of bankers before the campaign. The story based on Podesta’s stolen emails was given roughly the same prominence as the story on Russian election meddling.

Trump’s late- night apology statement wasn’t helping. Most of the commentary on it focused either on the strange way the video was shot— the background was a fake nighttime cityscape— or on the fact that the apology also included a personal attack on the Clintons. Christie later said Trump’s uncomfortable delivery made it seem like a hostage video.

At seven a.m., Priebus was back on the train, now heading, once again, to New York, because Trump had again summoned his inner circle at Trump Tower. This time they met in Trump’s gold-and-marble- adorned apartment on the sixty- eighth floor. As they began discussing what to do next, Trump asked Priebus what he was hearing. Christie and Bannon have both talked about Priebus’s response. And now here, for the first time, is what Priebus says happened.

“He asked what I was hearing and I told him,” Priebus told me. “I’m hearing that you can either withdraw or you can lose in the biggest landslide that’s ever been had.”

Others in the room, including Bannon and Christie, took that to mean Priebus was telling Trump he needed to drop out. Priebus insists he was just relaying what he had been hearing from influential Republicans around the country.

But did Priebus agree? Did he think Trump had only two choices: to drop out or to get creamed?

“Yes,” he told me long after Trump’s election victory had proved him wrong. “I believed it too.”

Priebus insists he had also already been telling people that it would be impossible to replace Trump as the nominee even if he did drop out. The party’s choice had already been ratified by the Republican convention in Cleveland and there was no practical way of undoing it. Besides, a dozen states had already started voting; absentee ballots had already been sent out in several others.

Regardless, Trump made it clear to everybody in the room he wasn’t going anywhere. With that question settled, the discussion turned to how to respond to a story that continued to engulf the campaign.

Melania was on hand for some of this discussion. She didn’t think her husband should drop out of the race, and that afternoon she put out a statement saying she had forgiven her husband and hoped voters would too. But she also didn’t think he had any chance of actually winning anymore.

According to another member of Trump’s inner circle there that day, at one point on Saturday afternoon Melania quipped, “Well, we won’t have to worry about moving anymore, will we?”

It was agreed that Trump should do an interview. There was talk of doing it with a friendly interviewer on Fox News. But the idea was rejected. To work, this had to be a serious interview; Trump could not look like he was avoiding tough questions. Someone suggested he do the interview with Jeanine Pirro, a die-hard Trump supporter.

“No, no,” said Rudy Giuliani when Pirro’s name was mentioned. “That wouldn’t be an interview; that would be a lap dance.”

And after lots of discussion, it was decided the interview would be that afternoon with my ABC News colleague David Muir.

The team broke for lunch, and Kellyanne Conway reached out to Muir to say Trump was considering doing an interview and if he did, Muir would likely get it. Muir had returned to New York earlier that afternoon on a commercial flight from Florida, where he had broadcast from the hurricane zone; NBC anchor Lester Holt and CBS anchor Scott Pelley happened to be on the same flight. Muir went to ABC News headquarters in Manhattan— located about a ten-minute cab ride from Trump Tower— and waited for the final word on the interview. An ABC News camera crew was in the neighborhood too, ready to set up whenever the Trump team gave the green light.

After the lunch, the Trump inner circle— minus Priebus, who took yet another Amtrak train back to DC— began to prepare for the interview by throwing out questions Trump was likely to get.

Conway asked, “How could any woman in America think you are fit for office when you use language like that?” Trump didn’t like the question, but he hated one asked by Christie even more.

“You go into great detail on the tape about what it is like to be a celebrity sexually,” Christie said to him. “How have you used your celebrity to get sex with women?”

Trump shot back: “You seriously think I have to answer a question like that?”

Trump got more and more agitated and eventually pulled the plug on the interview.

“F*** it, I’m not doing it.”

Conway called Muir and told him the interview was off. In his book Fear, Bob Woodward says Muir had helicoptered to New York to do the interview and was already set up with his camera crew in Trump Tower. That’s not true. Muir had been working up questions and preparing, but he never left his office at ABC News headquarters. The ABC News crew, however, had arrived at Trump Tower with campaign embed John Santucci. They were about to walk into the elevator to go up to Trump’s apartment and set up for the interview when Santucci got a text message from Hope Hicks telling him the interview was not going to happen.

Chris Christie was so demoralized by the way things were unfolding, he decided he would skip the debate the following day. He told the others he just needed to take a break and that Trump wasn’t listening to his advice anyway.

By Sunday morning, the day of the debate, all of the Republican Party’s leadership had run from Trump, including Speaker of the House Paul Ryan and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

“The cascade of Republicans that have fled Donald Trump includes elected officials from the Northeast, from the South, from the West,” I told George Stephanopoulos on ABC’s This Week that morning. “It includes the establishment, the Tea Party, the full spectrum of the Republican Party.”

But Reince Priebus, despite his dramatic admonition that Trump had to either drop out or lose in spectacular fashion, was one Republican who did not jump ship. Stuck between Trump and those who wanted Trump out, he teetered, he wavered, he told Trump he would suffer a historic loss if he remained in the race, but Priebus ultimately stayed with him. On Sunday morning, he was back on yet another train heading to New York again, this time so he could fly with Trump on his plane to St. Louis for the debate.

In this whirlwind, there was one more surprise yet to come. Bannon, Kushner, and Deputy Campaign Manager David Bossie had been quietly cooking up a plan to go on the offensive, opening up a new and ugly front in the war with the Clintons. While the Access Hollywood video had Republican leaders everywhere in a state of panic, Bannon had reached out to the women who had accused Bill Clinton of sexual misconduct over the years and asked if they would show up at the debate. Nobody knew their stories better than Bossie. As a conservative activist and an investigator for House Republicans in the 1990s, Bossie had helped lead the Republican crusade to impeach Bill Clinton two decades earlier. Among those contacted by the Trump team were Paula Jones, whose sexual harassment lawsuit against Bill Clinton set off the series of events that led to Clinton’s impeachment, and Juanita Broaddrick, who had accused Clinton of raping her back in Arkansas in 1978. They also brought Kathy Shelton, who accused a forty- one- year- old man of raping her when she was twelve years old. Hillary Clinton, then Hillary Rodham, represented her accuser, and Shelton has said Hillary mistreated her by coldly trying to undermine her credibility at trial.

On the campus of Washington University in St. Louis a few hours before the debate, the Trump team was gathered in a private space, continuing to prepare for the debate, when Bannon and Bossie got up and told Priebus they needed to take Trump to meet a group of people who had donated money to the campaign. They told Priebus he did not need to come. Minutes later, Priebus looked up and saw

Trump on TV, walking into a room not far from the debate hall with the women who had accused Clinton of sexual misconduct. The move shocked everybody, but nobody more than Reince Priebus.

As the debate was about to begin, I was positioned inside the hall, looking down on the stage. Just minutes before ABC News’s coverage began, I noticed the Clinton accusers being escorted to seats right by where I was standing. The Trump team had just tried to have them seated on the debate stage in the seats set aside for the families of the candidates. Here’s how I set the scene on live television one minute before the debate moderators, Martha Raddatz and Anderson Cooper, kicked off the debate.

“Those women who accused Bill Clinton are right over my shoulder here,” I said, with the women clearly visible over my left shoulder, “but Donald Trump, in terms of his party, comes into this hall a man alone. Party leaders who have not already abandoned him have stopped defending him. Others are watching tonight. A bad performance by Trump and they will leave en masse, taking party resources with them.”

In his first question to Trump, Anderson asked about the Access Hollywood video. In his answer, Trump both apologized and downplayed the significance of his words:

“This was locker-room talk,” he said. “I am not proud of it. I apologize to my family, I apologized to the American people. Certainly, I am not proud of it. But this is locker- room talk.”

And then he went on the offensive: “If you look at Bill Clinton, far worse,” Trump said. “Mine are words and his was action. His words, what he has done to women. There’s never been anybody in the history of politics in this nation that has been so abusive to women. So you can say it any way you want to say it, but Bill Clinton is abusive to women.”

Trump was done apologizing. He was back in the fight. To many of those outraged by what they had heard him say on the tape, the quick pivot to attacking Clinton over decades- old allegations against her husband made the apology seem insincere. Trump’s supporters, though, were cheering. After minutes of back- and- forth on the video, the debate turned to other topics. Trump sure didn’t seem like a guy ready to give up.

By the time the debate drew to a close, I had received text messages and emails from several Republicans who had been telling me the campaign was over and who now believed he would live to fight another day. Trump was wounded, but his campaign wasn’t dead yet.

“I’ve been in touch with a lot of Republicans during the debate,” I told George Stephanopoulos during ABC’s live broadcast right after the debate ended, “and my sense is that he has stopped the bleeding. I don’t think that he did anything to save himself with Republicans that have already jumped ship, but I think that he will stop the wholesale departure of Republican leaders. He took the case to Hillary Clinton, particularly on issues like Obamacare and her emails and taxes. The Republican base will applaud those attacks.”

Trump did recover. And, to a degree, so did Reince Priebus. He had told Trump he was doomed to lose, and after Trump won, he still managed to be named chief of staff. But it wasn’t a full recovery. Trump never forgot what Priebus had told him during his darkest hour. He sometimes brought it up during meetings at the White House— sometimes to embarrass his chief of staff, always to remind him that he would never forget.

Perhaps the biggest victor of all during the Access Hollywood weekend was Vladimir Putin. He got his four hundred fifty roses. He also received a much more valuable birthday present— one of the greatest political distractions of all time. The blockbuster news that Putin’s government had been caught by US intelligence trying to mess with our presidential election was pushed to the background by a scandal so big it convinced just about everyone that the Trump era was over.

We were all wrong. It was just beginning.

-- "Front Row at the Trump Show," by ABC News Chief White House Correspondent Jonathan Karl, is published by Penguin Random House.