Equal Rights Amendment: The century-long fight to codify women's rights into the Constitution

The amendment has been in the works since 1920 and passed a milestone in 2020.

A century-long battle to amend the Constitution to cement equal rights for Americans regardless of sex is coming to a head soon.

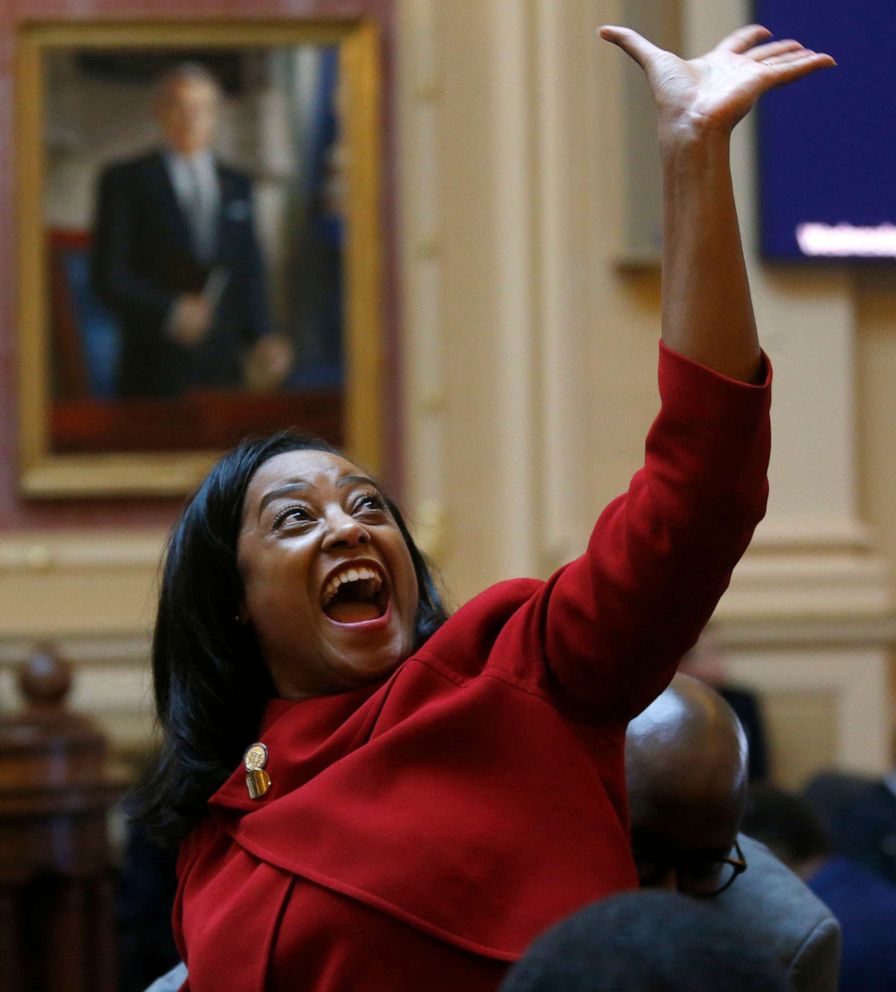

On Jan. 15, Virginia became the 38th state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment, crossing the three-fourths of the union threshold specified in the Constitution for its adoption.

However, the amendment may not see the light of day for a while, due to legal technicalities over a Congress-issued deadline, which are bound to lead to long court fights.

Here's a look at how the Equal Rights Amendment, or ERA, began and progressed, and where it will go in the weeks to come.

Origins in the suffrage movement

Activist Alice Paul pushed to have national protections for women and formally called for the ERA in 1920. Three years later, Congress introduced the amendment, which was authored by Paul. However, both the House and Senate sat on the proposal for decades.

Civil rights movement prompts action

Throughout the 1960s, women's rights groups and civil rights organizations lobbied Congress to pass the amendment and send it to states for ratification. Their efforts included rallies, disrupting hearings and public campaigns.

Their efforts paid off when, in 1971, the amendment passed in the House, followed by the Senate a year later. There was bipartisan approval for the amendment, which read, "equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

The amendment would give American women more protections and would be the basis for laws that granted equal pay and prohibited gender discrimination, according to experts.

Off to the states, the battle begins

When Congress sent its resolution to the states for ratification in 1972, it came with some stipulations, including a seven-year deadline to meet the 38-state minimum. Article V of the Constitution, though, does not give a specific time limit to ratify any potential amendment.

Although the ERA had big name supporters, such as the AFL-CIO, there was some opposition, particularly from conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly. She argued that the ERA would disrupt social norms and lead to hardships for housewives and possibly women being drafted into the military.

By the end of 1979, only 35 state legislatures ratified the ERA including Nebraska, Texas, Michigan and Oregon. Congress extended the deadline by another three years, but no additional state houses gave their seal of approval.

New push in the '90s

Although activists continued to lobby for the three additional states to ratify the ERA, there was little to no activity among those legislatures for a quarter-century. ERA supporters, however, were still determined, especially after the 27th Amendment was passed in 1992.

That amendment was originally sent to the states for ratification in 1789 and didn't meet its minimum state count until 1992. ERA proponents have argued that the deadlines issued by Congress in 1972 were part of the resolution to send it to the states and not in the actual wording of the amendment itself.

New millennium, new states

In 2017, Nevada became the 36th state to ratify the ERA, and a year later, Illinois approved the amendment. More and more advocates began calling on their elected officials to ratify the amendment including celebrities such as Alyssa Milano and Patricia Arquette.

In January, Virginia's state legislature, which had recently gained a Democratic majority after more than 20 years, ratified the amendment, passing the threshold.

Legal roadblocks make future murky

The congressional deadlines set in the original 1972 resolution continue to be a major impediment to ERA's adoption. Some legal experts contend that those deadlines prohibit ratification and the process would have to start over. However, others have argued that Article V doesn't deter ratification once the threshold is met.

The U.S. Department of Justice's Office of the Legal Counsel (OLC) released an opinion before the Virginia vote that stated the amendment "is no longer pending before the States," because of the expiration. The National Archives and Records Administration, which has to certify the amendment, said in a press release it would comply with the OLC's opinion save for a court order.

Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, told ABC News it is likely a lawsuit will be filed against the National Archives that will compel them to ratify the amendment.

There are bills in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate that seek to remove the deadline, which would negate any legal argument, according to experts.

"It's taken almost a century, but it's closer than we have ever been. We're determined to cross the finish line," Carol Jenkins, co-president and CEO of the ERA Coalition/Fund for Women's Equality, told ABC News.