Despite focus on Washington, data shows how shutdown hurt federal workers nationwide

Data shows Alaska, Wyoming, New Mexico and California were all hard hit.

It’s not clear yet what the lasting impact will be on federal workers furloughed in the longest-ever government shutdown -- even as Congress holds talks to avoid another one -- but a closer look at employee data nationwide paints a picture of the economic struggles many now might face because of the political standoff.

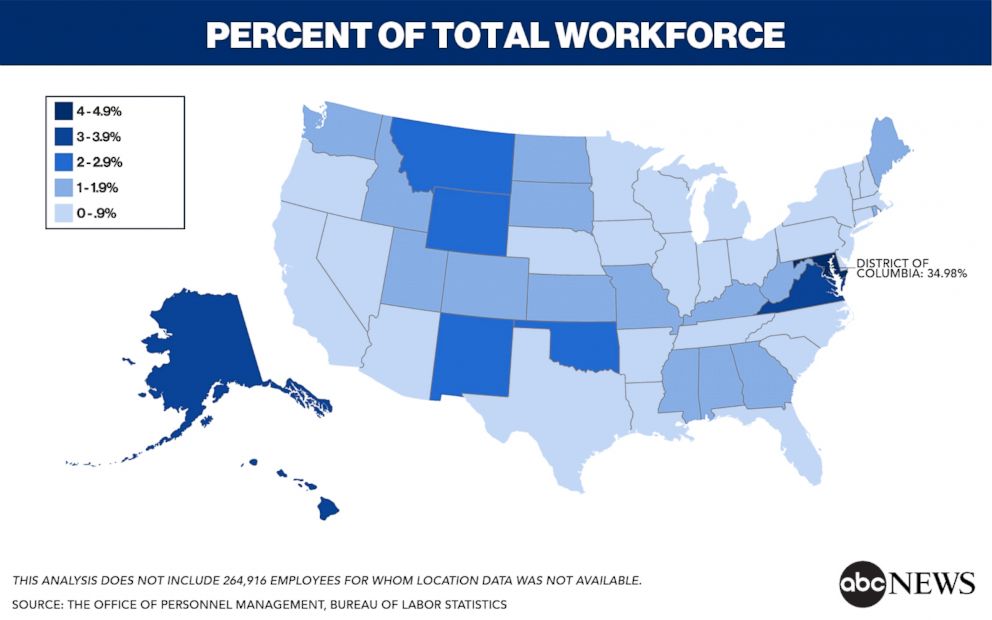

Here are more details on how and where they were affected, according to an ABC News analysis of the nearly 2.1 million federal employees across the country. The analysis also focuses specifically on Alaska, Wyoming, New Mexico and California -- all states where workers went without badly-needed paychecks and without the attention given to government workers in and around Washington.

One federal employee ABC News spoke with, Joshua Rider, works as a staff attorney with the Agriculture Department in San Francisco. His entire office was furloughed in the shutdown.

“We’re civil servants, and we do it in part because we value public service,” Rider said in an interview during the shutdown. "Regardless of the policy differences, we should not be using the federal workforce as hostages and leverage.”

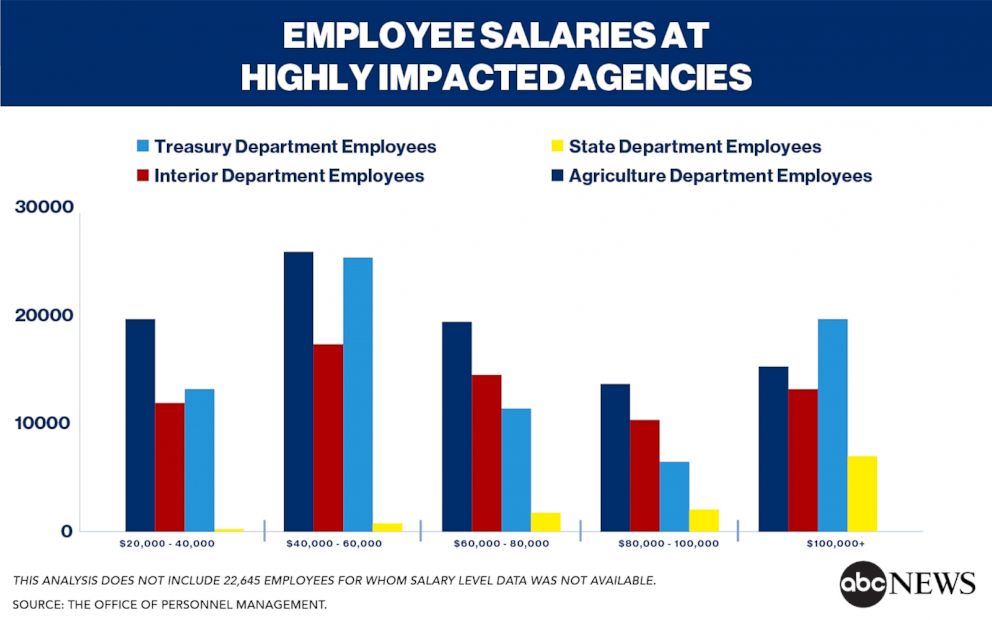

The Agriculture Department was one of four agencies ABC News took an in-depth look at as part of the analysis. The agencies -- the Agriculture, Interior, State and Treasury departments -- were four of the largest and most affected by the partial shutdown, according to the government contingency plans issued beforehand, and also had the most data publicly available.

The data shows the breadth of impact the shutdown had on Americans -- tens of thousands of whom were already making less than $40,000 a year working for the government.

For example, at least 19,300 workers make less than $40,000 per year at the Agriculture Department and about 13,000 make less than that at the Treasury Department.

In some states, those employees are more concentrated. In Wyoming, nearly a quarter of the state's federal workers make less than $40,000, and the same is true for about 15 percent of New Mexico’s federal workers. In Alaska, where salary data is available for roughly 11,400 federal workers, about 7 percent make less than $40,000.

And nationwide, at least 38,000 federal employees nationwide make less than $30,000 per year, about 2 percent of the government workforce, according to data from the Office of Personnel Management, which excludes salary details for more than 280,000 employees.

Over 38,000 federal employees make less than $30,000 each year, according to data from the Office of Personnel Management.

For context, a family of four with two children is considered in the poverty threshold if their combined income is less than about $25,000.

Government shutdown adds to years of economic stress in Alaska

Despite having one of the smallest populations in the U.S., Alaska has almost the same rate of federal employees in its workforce as Virginia.

Alaska was hard hit by the shutdown. Of the five federal agencies that employ the most Alaskans, three were significantly affected.

And the shutdown only added to the state’s existing problems: Alaska has the highest unemployment rate in the country, and as of December, estimates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, show the state has been in recession for nearly four years, due in part to a decline in oil prices, according to Mouhcine Guettabi, an economics professor at the University of Alaska’s Institute of Social and Economic Research.

“The federal jobs tend to be the best paid, and therefore the ones that really contribute to the economic vitality of those places,” Guettabi said.

“The spending by federal workers supports so many jobs, so many businesses — so if federal workers are not eating out, they’re not getting their haircut, they’re not spending money the way they’re accustomed to, then retailers are hurting,” he said.

More recently, Alaska was starting to see oil prices stabilizing — prompting optimism that the state is headed toward recovery — but the shutdown is “another hurdle in that potential recovery,” Guettabi said.

The federal jobs tend to be the best paid, and therefore the ones that really contribute to the economic vitality of those places.

In 2017, $1 billion of the state’s distributed payroll came from federal government wages — out of the $17 billion total distributed to Alaskans. Because of the shutdown, federal workers in Alaska missed close to $34.5 million in wages, according to estimates Guettabi provided.

“It certainly is not welcome news that there was more economic hardship in a state that’s already lost somewhere between 12,000 and 13,000 jobs over the last 3.5 years,” Guettabi said.

Wyoming, home to a large number of federal employees, suffered disproportionate impact

While states like Wyoming have a much lower overall number of federal employees, a relatively large portion of its labor force receives paychecks from the federal government.

In comparison to the nearly 287,000 people in Wyoming’s civilian labor force, a database of federal employees identifies 6,700 as located in the state. (This is likely an underestimate, as the database does not provide location data for roughly 265,000 federal employees nationwide.)

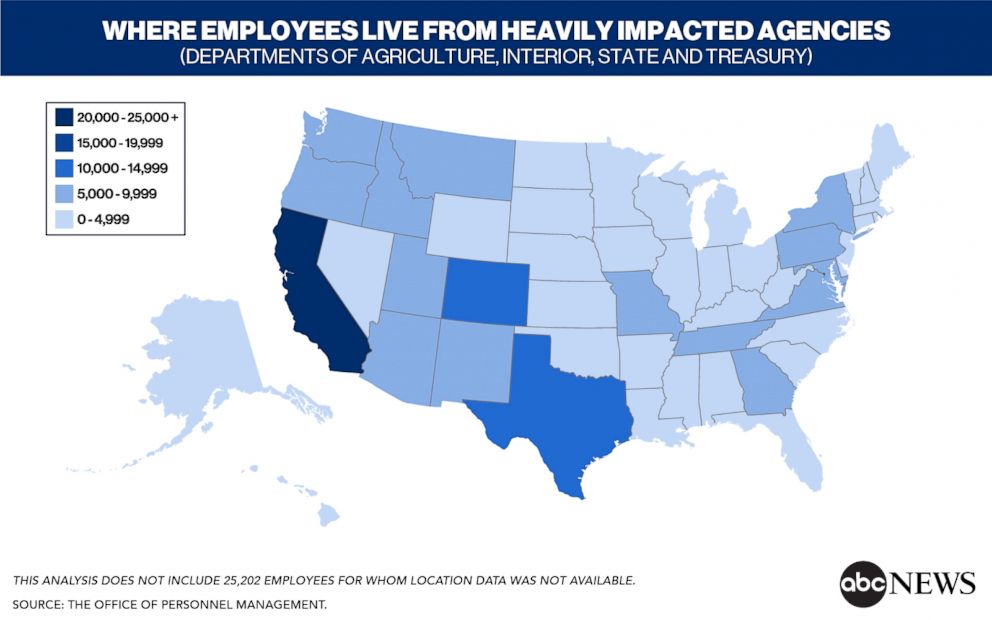

Taken together, the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Interior — two agencies heavily affected by the shutdown — employ more than 3,400 Wyomingites. That number represents more than 1 out of every 100 people in the state’s labor force.

To bring the state of Virginia back into play for comparison: While the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates Virginia’s civilian labor force is more than 15 times larger than that of Wyoming, Wyoming’s percentage of federal employees in its workforce is almost as high as in Virginia. And of the three agencies that employ the most federal workers in Wyoming, two were affected in a major way by the shutdown.

24 percent of workers for one affected agency live in four states

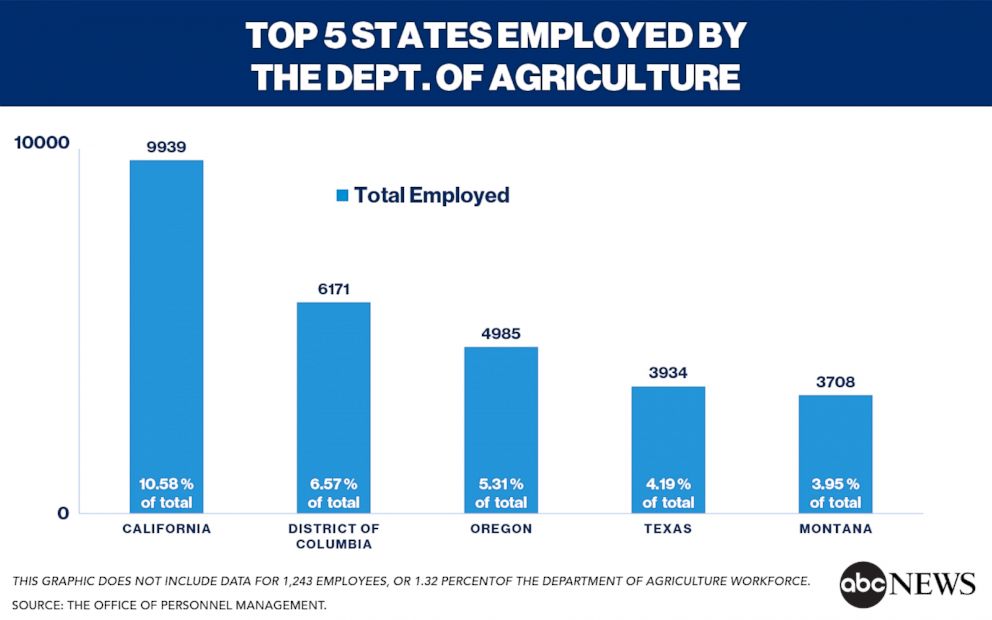

The Department of Agriculture employs people in all 50 states — but employs the most in California, Washington, D.C., Oregon, Texas and Montana.

Broken down, 6.5 percent of its workforce is in D.C. -- and 24 percent of the whole agency’s workforce -- is in the four states.

“When [people] think of the shutdown, they think largely of Washington, D.C., and the Northern Virginia and nearby Maryland suburbs — which are home to very large numbers of federal workers, and many of my colleagues whom I adore,” said Rider, the staff attorney with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Office of General Counsel in California, where almost 11 percent of the workforce is employed.

“But there is a vast federal workforce throughout the country,” Rider said.

When everyone in his office was furloughed, Rider said key services like environmental litigation and wildfire cost recovery cases were put on hold, but it also created another problem: employee discouragement.

As attorneys, Rider said, many in his office would be "substantially better compensated in the private market.”

Rider called it an “extra blow” that “the security and stability that you’ve counted on in a public service job has been so disrupted.”

Interior Department employees in New Mexico "held hostage": Democratic senator

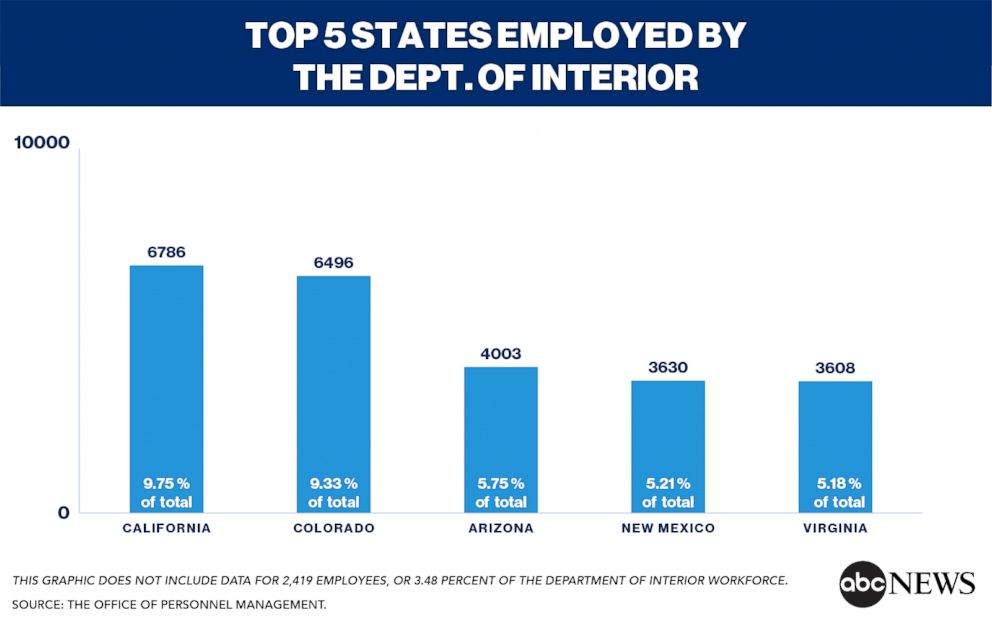

A large number of Interior Department employees were affected by the shutdown -- nearly 80 percent, according to the department’s contingency plan -- and more than 20 percent of them work in three border states: Arizona, California or New Mexico.

But New Mexico is also home to 23 tribes, which rely on government support for daily services.

“New Mexico is among the states that are hurt the most when the government shuts down because of our large federal workforce, the large tribal presence in our state and the importance of public services — from national parks to food assistance, to USDA loans — for our economic well being,” said Democratic Sen. Tom Udall.

“The shutdown hit native communities especially hard,” said Udall, who is the vice chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. “The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service were unfunded, furloughing thousands of workers. So critical public safety and health services were severely limited.”

Udall added that the complete impact of the shutdown in New Mexico will only be known in retrospect when the state can look back on the year’s tourism data.

“States like New Mexico simply can’t afford shutdowns,” Udall said. “This shutdown was a disaster for families across my state, and the effects, I think, will be long-lasting.”