The history of presidents conducting secret White House recordings

The history of secret White House recordings

— -- Following his firing of James Comey, on Friday morning President Trump warned the now former FBI director on Twitter that he “better hope that were are no ‘tapes’ of our conversations before he starts leaking to the press.”

When asked if Trump had recorded his conversations with the former FBI director, the president’s top spokesperson declined to comment.

"The president has nothing further to add on that," Press Secretary Sean Spicer said Friday.

Trump also refused to elaborate on whether there are any tape recordings: "I can't talk about that. I won't talk about that,” he said in an interview with Fox News that aired Saturday.

But the White House has a history of recording, dating back to 1940. Presidents from Roosevelt to Reagan had various types of audio recording devices installed to conduct secret tapings, and it was a White House practice that was relatively unknown until Watergate.

Franklin Roosevelt

FDR was the first president known to conduct recordings in the Oval Office. In the midst of campaigning for a third term, and upset over having been misquoted, Roosevelt approved the installment of a recording machine beneath the Oval Office, The idea was suggested to him by his stenographer, according to William Doyle’s book “Inside the Oval Offices: The White House Tapes from FDR to Clinton.”

According to the Miller Center, a policy and political history institute at the University of Virginia, the president had the recording device -- a RCA Continuous-film Recording machine -- installed in 1940, with the intent to capture press conferences. But the machine picked up some private conversations and meetings immediately before and after the press briefings. FDR also kept a microphone hidden in a lamp on his Oval Office desk, Doyle writes.

Roosevelt only used the recording machine for 11 weeks, and recorded 14 of the 21 press conferences he held in 1940. His recordings were not discovered until 1978.

Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower

Roosevelt’s successor Harry Truman inherited the machine and continued recording in the White House, though sparingly. The Miller Center found that Truman recorded about 10 hours of material, but only a few hours of the recordings are intelligible.

Dwight Eisenhower, however, was slightly more enthusiastic about the technology -- he recorded 25 meetings in the Oval Office, switching to a different recording system and hiding a microphone inside a fake telephone on his desk.

John F. Kennedy

During his presidency, John F. Kennedy significantly increased the scope of the White House recording operation. Kennedy had taped 260 hours of meetings in the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room, along with telephone calls.

According to the Kennedy Presidential Library, JFK had taping systems installed in 1962, but for no definitive reason.

Kennedy’s personal secretary Evelyn Lincoln and Secret Service agent Robert Bouck, who installed the taping devices, believed it was added to provide an accurate record for his memoirs or personal use after leaving office. Lincoln also recalled that Kennedy was irked after some of his advisers who supported the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion later claimed they opposed it during the fallout.

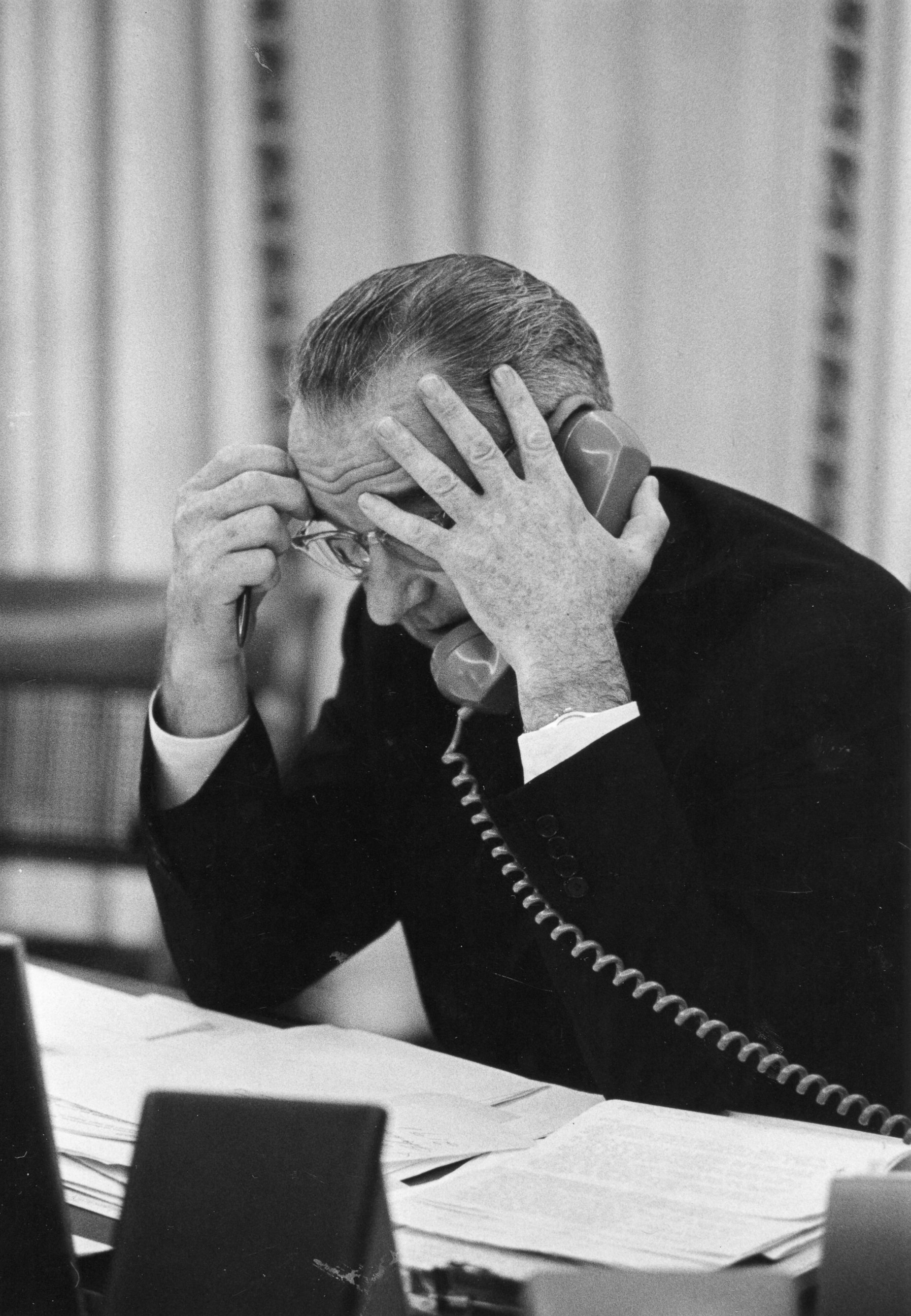

Lyndon B. Johnson

Besides Nixon, there was one other president who extensively taped conversations during his time in office -- Lyndon Johnson.

According to presidential historian Michael Beschloss, who’s written two books on Johnson’s tapes, he was recording on the first day of his presidency, when he was on Air Force One following Kennedy’s assassination and called Kennedy’s mother to express his condolences. The president also asked that some conversations be immediately transcribed by his secretaries.

Martin Luther King Jr., Bobby Kennedy and Nixon are just some of the people whose voices are heard in the 10,000 conversations Johnson taped. The bulk collection of records provided a window to how Johnson handled the biggest aspects of his presidency, including his work to pass civil rights legislation and the challenge of the Vietnam War.

“The tapes reveal him as the far more mesmerizing man he really was -- earthy, vulnerable, suspicious, affectionate, devious, explosive, funny and domineering. For someone so concerned about his public image, it is curious that he didn't simply destroy the tapes,” Beschloss wrote in a 1997 Newsweek article.

In one particular tape from 1964, Johnson is recorded ordering new pants, using rather colorful language to describe how he wanted the pants tailored.

LBJ had wanted the tapes to remain sealed for 50 years following his death, but his presidential library began releasing them in 1993.

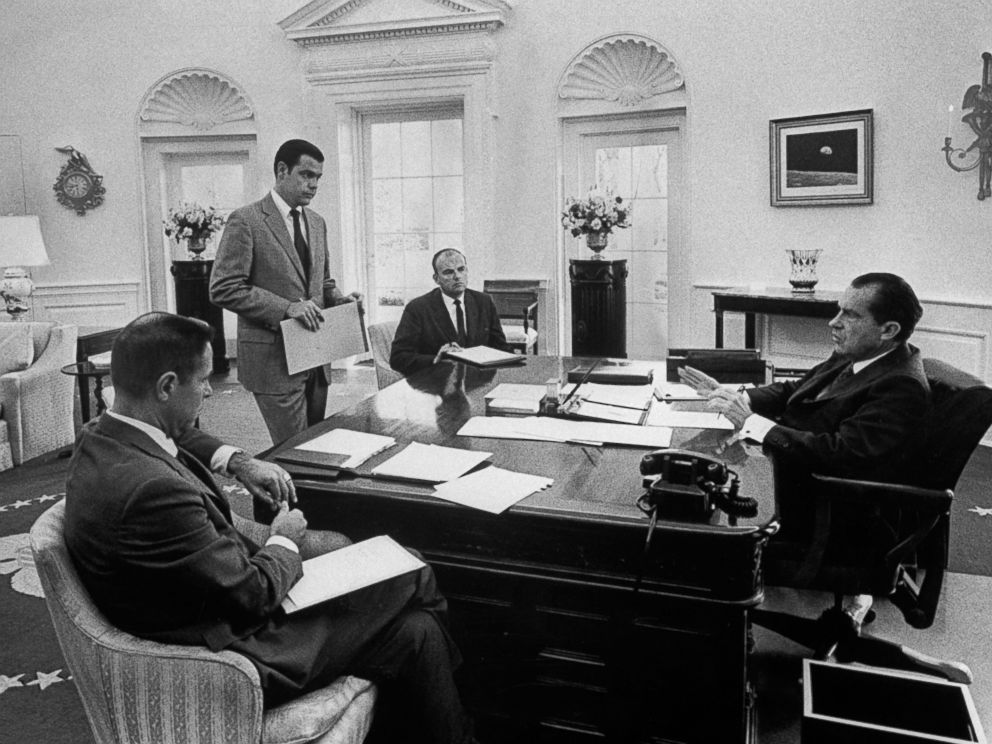

Richard Nixon

Trump’s critics argue his tweet to Comey invoked the most infamously known case of a president conducting secret recordings. Nixon recorded conversations and meetings for nearly half of his presidency. The result: 3,700 hours of recordings, with one “smoking gun” that eventually led to Nixon’s downfall.

On July 16, 1973, Nixon aide Alexander Butterfield revealed the secret recordings existed during a hearing in front of the Senate Watergate Committee. On one of the many tapes, Nixon discussed with his chief of staff H.R. Haldeman how to thwart the FBI’s investigation into the 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Convention headquarters in the Watergate building in Washington.

A subpoena for the tapes from special prosecutor Archibald Cox was the impetus for his firing by Nixon, in what became known as the "Saturday Night Massacre."

Ronald Reagan

But Nixon wasn’t the last to employ a secret recording system. Through a Freedom of Information Act request, Doyle uncovered a trove of phone calls from Ronald Reagan to foreign leaders.

In one such call, Regan asked Pakistani President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq not to give concessions to the hijackers of TWA Flight 847. “I think we would just see more hijackings then and more terrorism,” he said.

In a 2011 interview with the New York Post, Doyle said Reagan limited his recordings to official business with heads of state, chiefly in the interest of overcoming bad translators and dropped calls.

No president since Reagan has admitted to recording calls, he added -- presumably because of the legal and political risks it entails.