K2 veterans demand investigation into deadly exposure: 'Congress needs to act'

Documents show the Defense Department was aware of radioactive uranium on base.

Former Senior Airman Kelly Earehart used to joke with his friends about what they were being exposed to while deployed in Uzbekistan.

"Watch out for that puddle -- it could be chemical weapons," he remembers saying.

The reality now is less light-hearted.

"Two of my good friends are dead," he told ABC News. "And I believe it has something to do with K2."

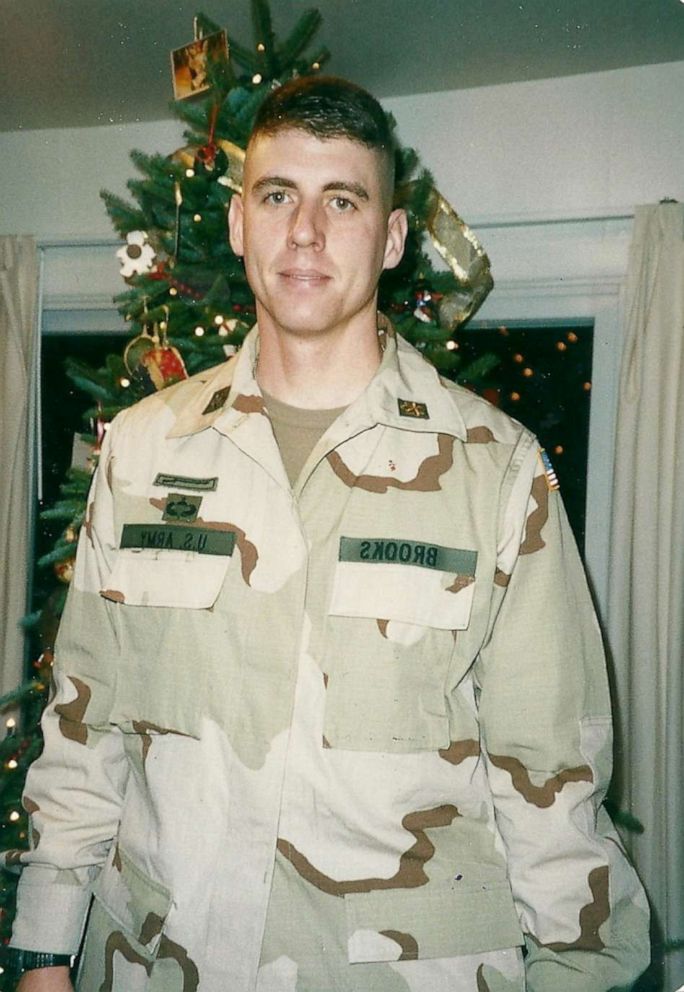

Kim Brooks, of Norwood, Massachusetts, had a similar suspicion following the death of her husband, former Lt. Col. Timothy Brooks, who also served at Karshi-Khanabad, commonly referred to as K2. Because of its convenient location a few hundred miles from al-Qaeda and Taliban targets in northern Afghanistan, the U.S. leased the former Soviet base from the Uzbek government following the 9/11 attacks.

Brooks had no answers to her questions until December 2019 when a McClatchy investigation revealed the Department of Defense was aware of harmful exposure at K2 but still kept troops there.

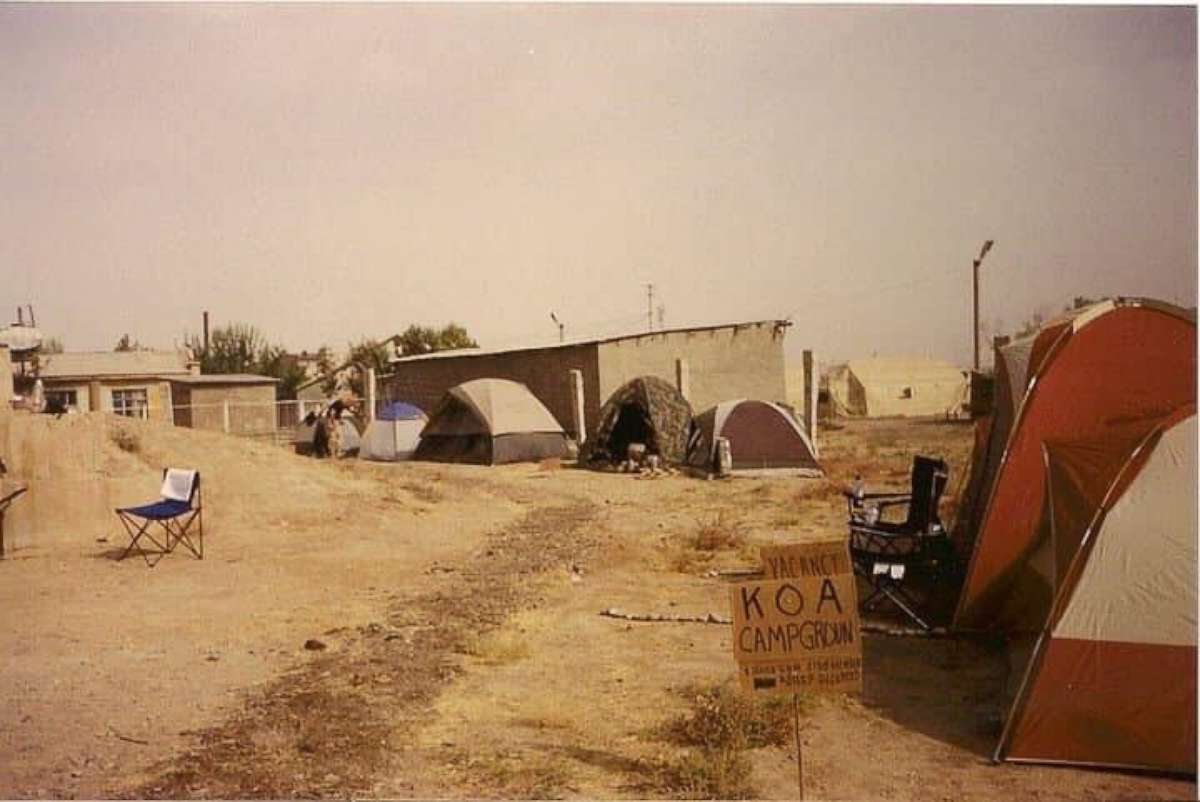

A report from November 2001 by the Army Public Health Center found areas of the base "contaminated with asbestos and low-level radioactive depleted uranium," both caused by the destruction of Soviet missiles.

After the McClatchy investigation came out, Brooks discovered a Facebook group for K2 veterans and family members.

Last week, Brooks flew to Washington and met up with two other K2 veterans from the group to advocate for the government to acknowledge the health risks troops were exposed to on base. The group is also demanding the Department of Veterans Affairs provide medical care for all K2 veterans experiencing an array of health problems and financial benefits to families who have lost a K2 veteran in the years since.

During an event at the National Press Club on Feb. 5, VA Secretary Robert Wilkie was questioned about the issue. He said the VA is "working with the DOD to get to the bottom of it," encouraging K2 veterans to come forward in the meantime.

"The message I have for all veterans who have been exposed to something at K2 is come see us," he said. "File the claims. Come speak to us."

In a statement to ABC News, a DOD spokesperson reiterated their partnership with the VA, saying there is a group that "meets monthly to coordinate interagency efforts related to various environmental exposures."

"The concerns about exposures at K2 had not come to the attention of the working group until December 2019," the spokesperson said. "The group is now actively working on this issue."

"The department does not take official position on the causality of the illnesses in question, including whether or not they are deployment related," the spokesperson added.

However, in an intelligence review from November 2001, obtained by McClatchy, U.S. Central Command found four hazards contributing to contamination of K2: a missile storage facility that had exploded in June 1993, an abandoned fuel storage facility, an abandoned aircraft maintenance facility and runoff from a chemical weapons decontamination site, which appeared on U.S. intelligence imagery in 1987.

"I feel betrayed on behalf of my husband," Brooks said. "He is duty, honor, country all the way. Tim took an oath to protect our country and our Constitution. He would be horrified to know that our government literally left our troops there."

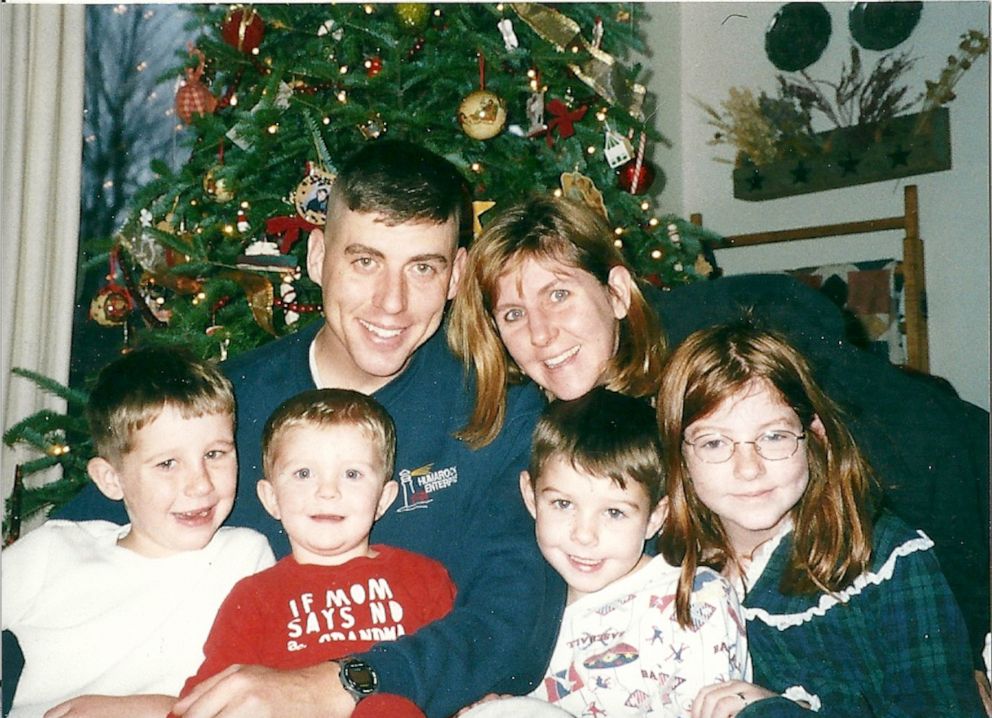

In November 2001, Tim Brooks celebrated Christmas early with his wife and their four children at their home at Fort Drum in New York. The following morning, he left for his deployment to K2. At the time, she was unaware she only had two Christmases left with her husband before he died.

After the 9/11 attacks occurred, he was one of about 7,000 troops stationed at K2 from late 2001 through 2005, which is when Uzbekistan withdrew permission for the U.S. to use the base.

While he was living on base, Kim Brooks remembers her husband telling her about "black goo" coming up from his tent.

"He told me he was waking up with this stuff all over his face and pores, his ears, just covering his body," she said. "He had no idea what it was. He was worried, but continued to execute his mission."

After his time at K2, Tim Brooks flew to Afghanistan and returned home to Fort Drum in spring 2002. It was at a post-deployment meeting when he first learned about his exposure to radioactive uranium.

"He came home and told me that they were exposed to some really bad stuff," Brooks recalled her husband saying. "He was upset about it. And I think as a family, we filed that away. He went back to his job, and within the next year, they were heading to Iraq."

In May 2003, she joined her husband at a pre-deployment meeting at Fort Drum. His unit was scheduled to depart for Iraq the following week. She remembers her husband saying he didn't feel well. She followed him into the hallway, where he collapsed and had a grand mal seizure.

One year and a day later, he died of stage three astrocytoma brain cancer. He was 36. Because he was on active duty at the time of his diagnosis, his family received full military benefits -- assisting them with medical bills and eventually, the education of their four children. Kim Brooks said the financial help has meant "less anxiety, knowing my family was supported in that way."

But it was through the Facebook group that she realized her husband's cancer was not an isolated incident, and she believes it could have potentially been prevented had the DOD relocated troops from the base.

Master Sgt. David Justiss was deployed to K2 four separate times from 2002 to 2004. He contracted shingles while at the base, and said the doctor told him his "immune system was compromised by the toxins at the base."

"I basically got a disease in my mid-30s that I shouldn't have gotten until my 60s," he said.

Justiss said he's disappointed by the lack of follow up from the government.

"One of the things that you're always told -- and always believed -- is that throughout your career, if something happens to you, they're going to take care of you," he said.

Former Master Sgt. PJ Widener, Jr. and former Staff Sgt. Derek Blumke joined Brooks in Washington and throughout the week, they met with members of Congress and other departments to push for their demands.

The group's goals are to schedule joint hearings and investigate what happened at K2, identify all service members who were deployed and inform them of what they've been exposed to and treat every person who has been medically affected by the exposure -- regardless of whether or not they are on active duty now, Blumke said.

Rep. Stephen Lynch, the chairman of the National Security Subcommittee, which is under the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, met with the group and told ABC News that he is "troubled" by the number of veterans suffering from illnesses attributed to the contamination at K2 -- and how the VA "refuses to recognize potential health risks associated with their deployment."

Lynch wrote a letter with Rep. Carolyn Maloney, the committee's chair, to the VA secretary and Defense Secretary Mark Esper on Jan. 3, requesting documentation of conditions at K2. They asked to receive the documents by Jan. 24, but Lynch said the deadline was not met.

"To date, neither agency has produced a single document in response to our requests," Lynch said. "Time is of the essence for these veterans, many of whom are battling advanced-stage cancers, and the Department of Defense and the VA owe it to them to respond as quickly as possible."

Maloney echoed Lynch on the importance of a timely investigation.

"U.S. service members put their lives on the line every day to protect us, so I am extremely concerned about reports that they were potentially exposed to cancer-causing chemicals, and the Pentagon did not protect or warn them," she said.

Widener started the K2 Facebook group in 2012. It now has more than 3,000 members, 341 of whom report they have cancer, and hundreds more who say they have other conditions -- everything from chronic migraines to nerve conditions.

Brooks said her visit to Washington "opened some wounds," especially as she continues to learn about families who have not received the same acknowledgment and financial support from the government that she did. However, she said she feels it's "her duty" to get help for other veterans in her husband's memory.

"It feels like a reckoning to me," she said. "A validation of some sort that I never wanted. I never wanted to hear that others are sick. And bottom line, now that this is out there, Congress needs to act."