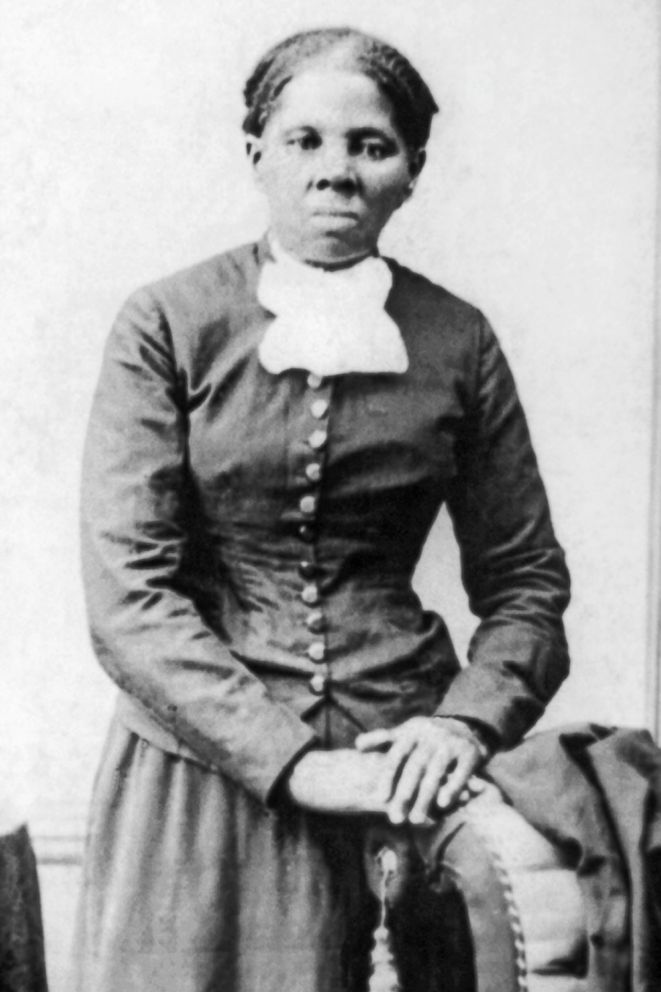

Lawmakers renew call to put Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill

She was a noted abolitionist and celebrated Civil War spy.

Harriet Tubman, noted abolitionist and celebrated Civil War spy, might be closer to getting on the $20 bill if renewed congressional efforts are successful.

Rep. John Katko, R-N.Y., made the case to use the image of the woman who helped hundreds of slaves escape to freedom via the "Underground Railroad" rather than that of former President Andrew Jackson, who owned slaves and who supported policies that led to the forcible removal of Native Americans from their homes.

Katko on Tuesday highlighted the importance of the Harriet Tubman Tribute Act.

"It should not even be an issue, in my mind," he told WKRN. When the Trump administration came in, it fell by the wayside."

Former Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew announced plans for Tubman to replace President Jackson on the $20 bill in 2016 as part of an effort to get more women on U.S. currency. The plan was set to go into effect in 2020.

However, the Trump administration has held off on implementing the plan. At a 2016 town hall on NBC's "The Today Show," President Donald Trump called the move "pure political correctness" and suggested putting Tubman on the $2 bill.

In 2017, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin told CNBC, "Ultimately, we will be looking at this issue. It's not something I'm focused on at the moment."

Katko and Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Md., reintroduced the Harriet Tubman Tribute Act this February after the initial bill died in committee in 2017. In a press release earlier this year, Cummings said, "Placing Harriet Tubman on our U.S. currency would be a fitting tribute to a woman who fought to make the values enshrined in our Constitution a reality for all Americans."

Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., introduced the measure in the Senate this March and the bill is before the Financial Services Committee in the House.

Tubman was born into slavery on a Maryland plantation in 1822 as Araminta Ross and changed her name after marrying her first husband. She escaped slavery 1849, and, as a key figure in the Underground Railroad, returned to the South at least 13 times to help free others.

During the Civil War she was a nurse and a spy for the Union Army. After the war, she petitioned the government to have her widow's pension increased given her additional wartime service.

In 1899, 34 years after the end of the war, Congress passed a bill raising her pension to $20 a month.