Michigan’s 'fairer' election maps challenged for 'diluting' Black vote

Some Detroit Democrats say redistricting has reduced Black voters' influence.

Michigan, one of the nation's hottest political battlegrounds, is being hailed for a citizen-led effort to transform its famously gerrymandered election maps into some of the fairest and most competitive ahead of the fall midterm elections.

"This is just one small step to start taking power back and even the playing field for voters to be able to actually control our elections and get the results we want," said Katie Fahey, the 32-year-old independent from Grand Rapids who sparked the grassroots redistricting reform movement with a 2016 Facebook post.

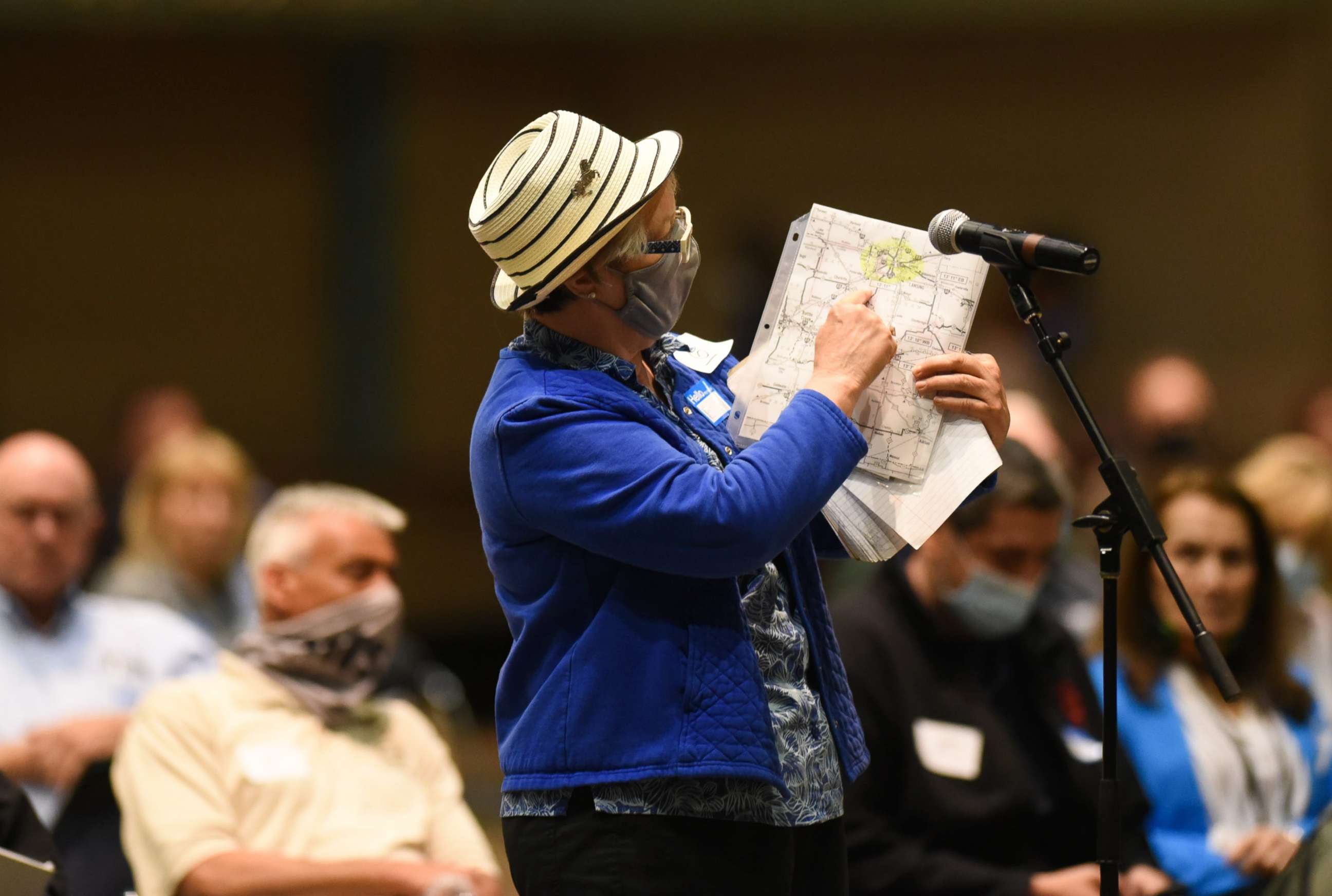

The state's closely watched experiment in redistricting by independent commission -- rather than by partisan state legislators -- could provide a model for other communities gripped by political polarization, experts say. Only eight other states limit direct participation of elected officials in the drawing of state and federal districts.

"People, when they go to the polls, they want to think that their vote matters. Whereas a lot of the time, when seats are gerrymandered to favor one party or the other, basically no matter what, those elections won't be competitive," said Nathaniel Rakich, a FiveThirtyEight senior elections analyst.

"The [new Michigan] map just does a really good job of making sure that neither Democrats', nor Republicans' votes are wasted," Rakich said.

But six months before Michigan's voters can put the new maps to the test, a barrage of partisan legal challenges threatens to blunt an achievement praised by the likes of former Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and former Democratic President Barack Obama.

"Are these maps better for partisan fairness? Yes. Could they be better? Absolutely," said state Sen. Adam Hollier, a Democrat who represents historically majority Black neighborhoods in metro Detroit.

Hollier is among a group of Detroit Democrats who allege in a state lawsuit that the maps "dilute" the power of Black voters in violation of the Voting Rights Act. African American voters are "almost completely politically silenced," the complaint claims.

Republicans, who have controlled both chambers of the state legislature for years, allege in a separate federal lawsuit that the newly drawn political districts aren't of equal population size as legally required and unlawfully split up several cities and counties.

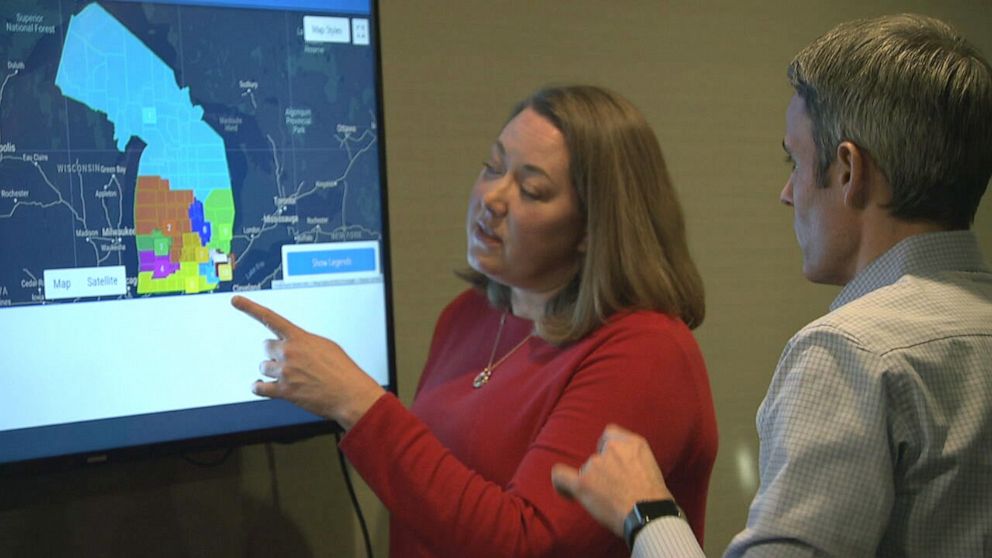

"I think we did a very good job of sort of putting our individual feelings on the shelf and making sure we were doing what was best for the people of Michigan," said Rebecca Szetela, a lawyer, mother of four and political independent who chairs the state's first 13-member Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission.

"I think that the maps should be fair and balanced moving forward, and I think that people will feel once again that their vote is their voice and that they have the ability to elect someone that represents them," Szetela said.

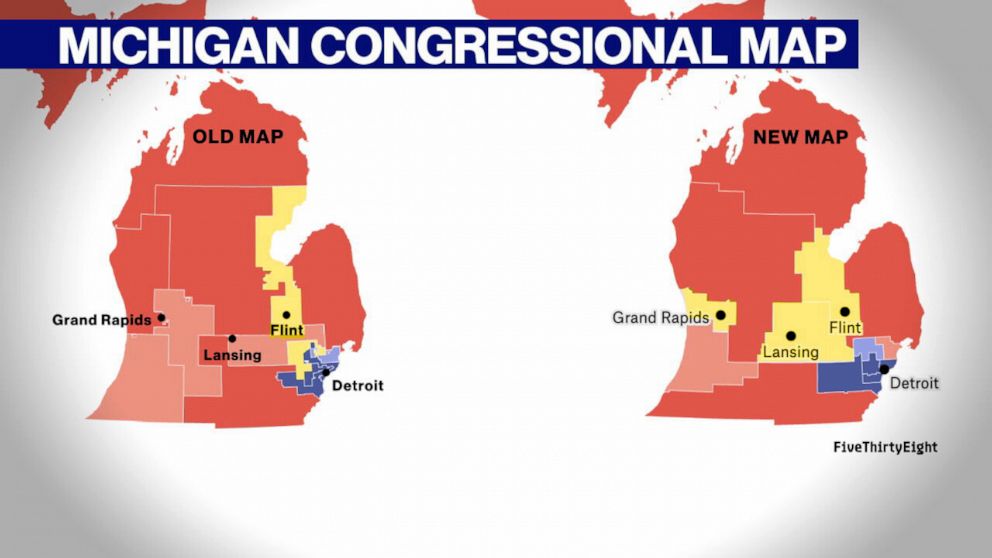

Michigan's old state and federal political districts -- in place for the past decade -- have been considered some of the most unfair and unbalanced in the country -- drawn by Republicans, to favor Republicans. Just two of the state's 14 congressional districts are rated as competitive by FiveThirtyEight.

"Michigan's a super purple state. About 50% of us vote for Democrats; about 50% of us vote for Republicans," said Fahey. "But depending on what party had gerrymandered, that party would have like a supermajority and be able to pass whatever kind of legislation they want, even though theoretically, we should have compromise on almost every single bill."

The new maps are cleaner, fairer and more competitive for both parties, according to FiveThirtyEight's nonpartisan Redistricting Tracker. It achieves this by unpacking the gerrymandered majority Black and heavily Democratic districts around Detroit, spreading those voters across new districts creating a blend of urban and suburban voters.

Yvette McElroy Anderson, a longtime community advocate and field director of the Fannie Lou Hamer Political Action Committee, said the disappearance of majority Black districts will make it harder for minority candidates to get on the ballot. .

"It's hurting the ability of Black candidates as well as hurting African Americans to have people that will represent the interests that needs to be represented on their behalf," Anderson said. "Fifty-one percent or better is what the Voting Rights Act says. So if we don't do that, then we are doing a disservice to the African American population."

Hollier, who is challenging the commission to go back to the drawing board before the state's August primary election, argued that it's possible to achieve districts that are both majority Black and more competitive.

"Black candidates, particularly from urban communities, and from across our state, have typically raised less money because there's less money in their districts," Hollier said, "and we talk about how much money has impacted politics. It changes who can run for things, and where the elected officials come out of."

Szetela argued that the new maps will enhance the power and influence of Black voters in more races and create more opportunities for representation. The two new congressional districts in metro Detroit would have roughly 44% African American voter representation.

"The data that we were looking at showed that even with lower percentages, that Black voters will be able to elect their candidates of choice," she said. "And because we divided up some of those districts that were historically 80 to 90% African American into more districts, there should be better representation."

Rakich said the debate doesn't have an easy answer.

"On one hand, [the critics] do have a point because certainly a district that is 44% Black is less likely to elect a Black representative," he said. "But at the same time, because of our system of elections, it's also very likely that even a 44% Black district would elect a candidate preferred by Black voters."

State and federal courts will likely decide the fate of Michigan's new maps, and it's the voters in November's midterm elections who will put them to their first big test.

"As a lawyer, I'm never confident on what's going to happen in a court because courts can rule any way that they want to," said Szetela. "At the end of the day, we did our good faith effort to come up with very good maps for the people in the state of Michigan."

Fahey, who is now counseling at least 13 other states on redistricting reform, said she's confident that no matter where the lines are drawn, the commission's impact will be a positive change over the old maps.

"It means that we'll have more competitive elections; it means that we'll probably have some more moderate candidates who are actually listening to both Democrats and Republicans," she said.