Philadelphia’s tale of two cities: Wealthy residents get tested at higher rates than poorer residents: ANALYSIS

Black neighborhoods in Philadelphia's metro area also have fewer testing sites.

Funeral director John Price, 72, had just gotten a break after a long day picking up bodies of COVID-19 victims from local hospitals in June. So he thought it was the perfect time to get tested himself for the coronavirus.

Price pulled his car into a line of approximately 300 others waiting for a test at a church parking lot on Cheltenham Avenue in North Philadelphia. Two hours in, he started getting calls from clients who had just lost loved ones to COVID-19. Another hour into his attempt to get a test, Price realized that he just couldn’t wait any longer.

“I had to pull out of the line, because I had people who were calling me,” he said. “It was probably going to be another two or three hours before they got to me. If they got to me.”

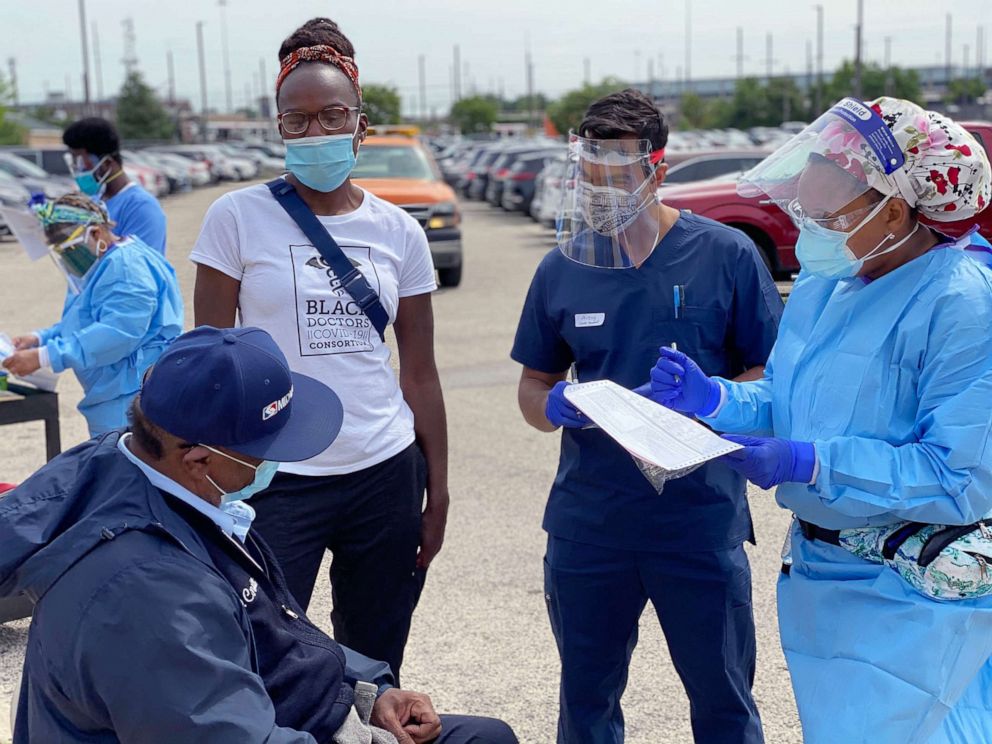

He went another week without getting a COVID-19 test until he stumbled upon a walk-in testing site organized by Dr. Ala Stanford’s Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium, which was offering the tests for free.

“A lot of people weren’t notified of how they can actually get testing,” said Price, recalling confusion amongst residents when the outbreak first began in the predominantly Black neighborhood of West Powelton, where his funeral home is based. “It was more like word of mouth, ‘Oh this organization is doing it today over here, or so-and-so is doing it today over there.’”

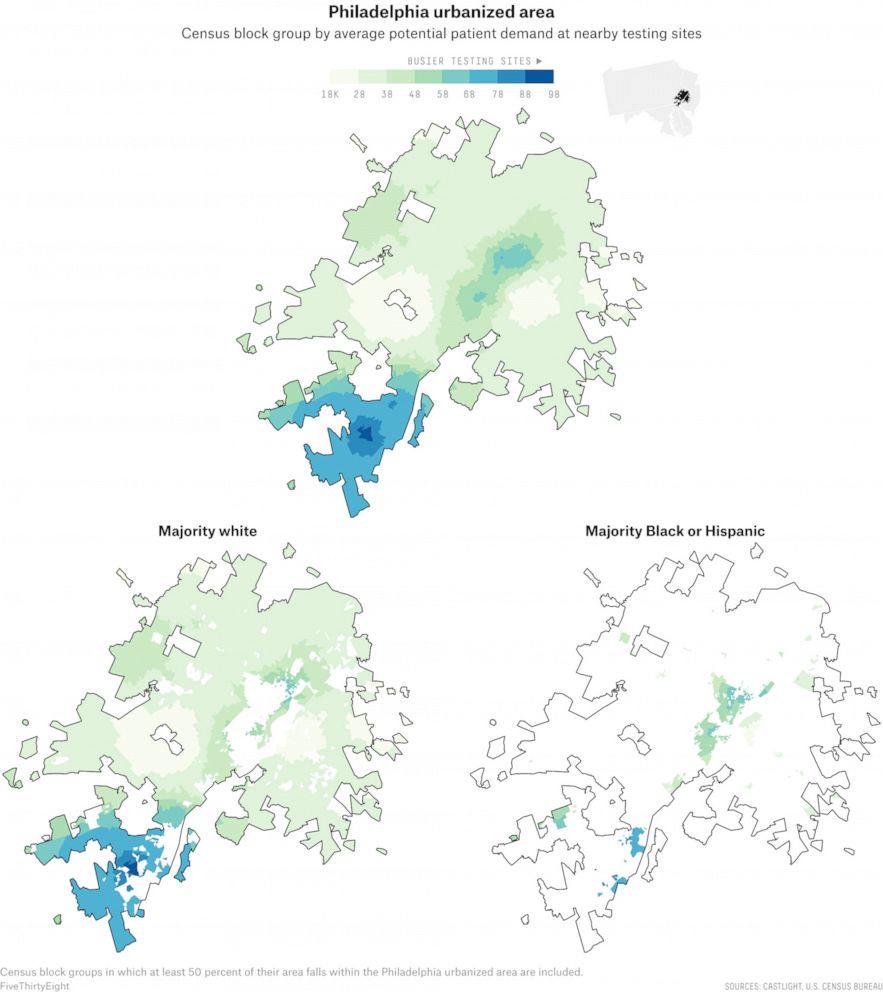

As the coronavirus crisis intensifies nationally, predominantly Black neighborhoods in the Philadelphia urbanized area, which extends into New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland, have fewer testing centers than their wealthier and whiter counterparts, according to a new, extensive review of testing sites by ABC News, FiveThirtyEight and ABC-owned television stations.

Our analysis found that sites in communities of color in many major cities -- including Philadelphia-- face higher demand than sites in whiter or wealthier areas in those same cities. The result of this disparity is clear: People of color, especially Blacks and Latinos, are more likely to experience longer wait times and understaffed testing centers.

This nationwide review is one of the first to look at testing site locations coast to coast, in all 50 states plus Washington, D.C., using data provided by the health care navigation company Castlight Health (the same data that Google Maps uses to surface COVID-19 testing sites). An assessment of city and state health department websites also revealed, over and over, fewer testing sites in areas primarily inhabited by racial minorities.

Importantly, our analysis does not factor in the capacity of testing sites -- which can vary from just 50 tests at one site to 2,000 at another, meaning that one site might be equipped to serve a larger number of people than another site. Instead, it looks at the potential demand for each site based on the number of people and sites nearby. The data we used also is less likely to reflect tests done in private physicians’ offices than federally-funded community sites, local government-run mobile pop-up sites, urgent care clinics and hospitals. The analysis also doesn’t take into account other factors that could determine testing accessibility, such as staffing and wait times, as well as other restrictions on testing like appointment or insurance requirements.

Other researchers, conducting independent analyses of other data, observed the same phenomenon ABC News did regarding the demands placed on testing sites in majority-white and majority-Black neighborhoods at the city level, despite the fact that Black Philadelphians make up a plurality of COVID-19 test recipients in the city.

Drawing on his own study of access to COVID-19 tests in various Philadelphia neighborhoods, which he has been tracking since the outbreak began, Drexel University epidemiologist Dr. Usama Bilal found that testing disparities are often a product of existing systemic inequalities. Rates of testing, he said, were lower in poorer areas and areas with higher proportions of residents who are racial minorities. Testing access improved throughout the city in April and May, Bilal found, but as cases start to resurface and the demand for tests rises, he worries the city will backslide.

“We’ve been observing that testing access is going the wrong way again,” he said. “Testing is becoming more concentrated in wealthier areas in Philadelphia, and we have observed a similar pattern in Chicago and New York.”

A Philadelphia public health department spokesman denied that testing is increasingly inaccessible to racial minorities and said that the city has been focused on expanding resources in underserved communities, citing services like the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium, which recently received city funding to conduct free coronavirus tests.

But Stanford, the surgeon who heads the consortium, said she worried that as the demand for testing increases nationwide, the share of tests she will be able to offer free of charge will fall.

“We’re out here in the sun, in the rain, doing whatever we can do in a mobile unit begging for supplies from everywhere else in the United States, waiting 10 days to get our results back,” she said. “But yet, in some of the best hospitals in the nation you have an in-house test that the residents of this city do not uniformly have access to. That’s a problem.”

According to the city’s public health department, Philadelphia has conducted more than 166,000 COVID-19 tests. Black residents account for 40 percent of the city’s COVID-19 tests, more than any other racial group tested and about equal to the share of Philadelphia that is Black, per city data.

Bilal’s research, however, now finds that in predominantly Black and highly populated areas like the Oxford Circle neighborhood of Philadelphia, where the median household income is $41,000, just 60.9 per every 1,000 people are now getting tested. Compare that to the more affluent and plurality white Center City neighborhoods, where testing rates are now 133 per every 1,000 people, according to Bilal.

“The epidemic that we really need to control long term is social inequality,” said Bilal as the coronavirus outbreak in Philadelphia first began to take hold. “It has many different intersecting axes. So there is racism: that is places, that is classism, that is gender discrimination, there are many, many things going on there.”

Indeed, the Philadelphia area illustrates the extent to which disparities in coronavirus testing access grow out of longstanding systemic inequality in American society. Philadelphia is one of the poorest big cities in the nation, with about 25 percent of residents living below the poverty line. Bilal found that while the distribution of testing sites in Philadelphia has vastly improved from where it was at the beginning of the outbreak -- with multiple options now available for residents even in the poorest areas -- Black Americans in many low-income areas are still likely to find it difficult to get a COVID-19 test. Our analysis of the sites active in mid-June confirmed this.

In Kingsessing, a southwestern neighborhood that’s around 80 percent Black, there’s only one COVID-19 testing site, and that site has limited testing hours. Meanwhile, in the Center City area, there are several sites -- some within a short walking distance of each other.

“This is exactly the ‘I can’t breathe’ moment as it regards health because we have the numbers, we have the statistics, we’re seeing who’s most disproportionately impacted by this disease, and absolutely nobody cares,” said Jenkins, the University of Pennsylvania health economics fellow.

This is an argument city officials reject, referencing the increased number of testing centers in north Philadelphia and other predominantly Black neighborhoods.

“The city is and has been focusing resources to expand COVID-19 testing in traditionally underserved communities in Philadelphia through community organizations and targeted funding,” said a Philadelphia Department of Public Health spokesman. “There is no truth to the statement that Philly is going the wrong way in terms of tests by opening more testing centers in wealthier Philadelphia communities.”

As is the situation in Philadelphia, many cities are now responding to calls to provide more resources to communities of color by increasing the number of pop-up sites to accommodate residents and ease the demand for more tests.

ABC News’ Briana Stewart and FiveThirtyEight’s Rachael Dottle contributed reporting.