New push to honor Black D-Day hero denied valor award

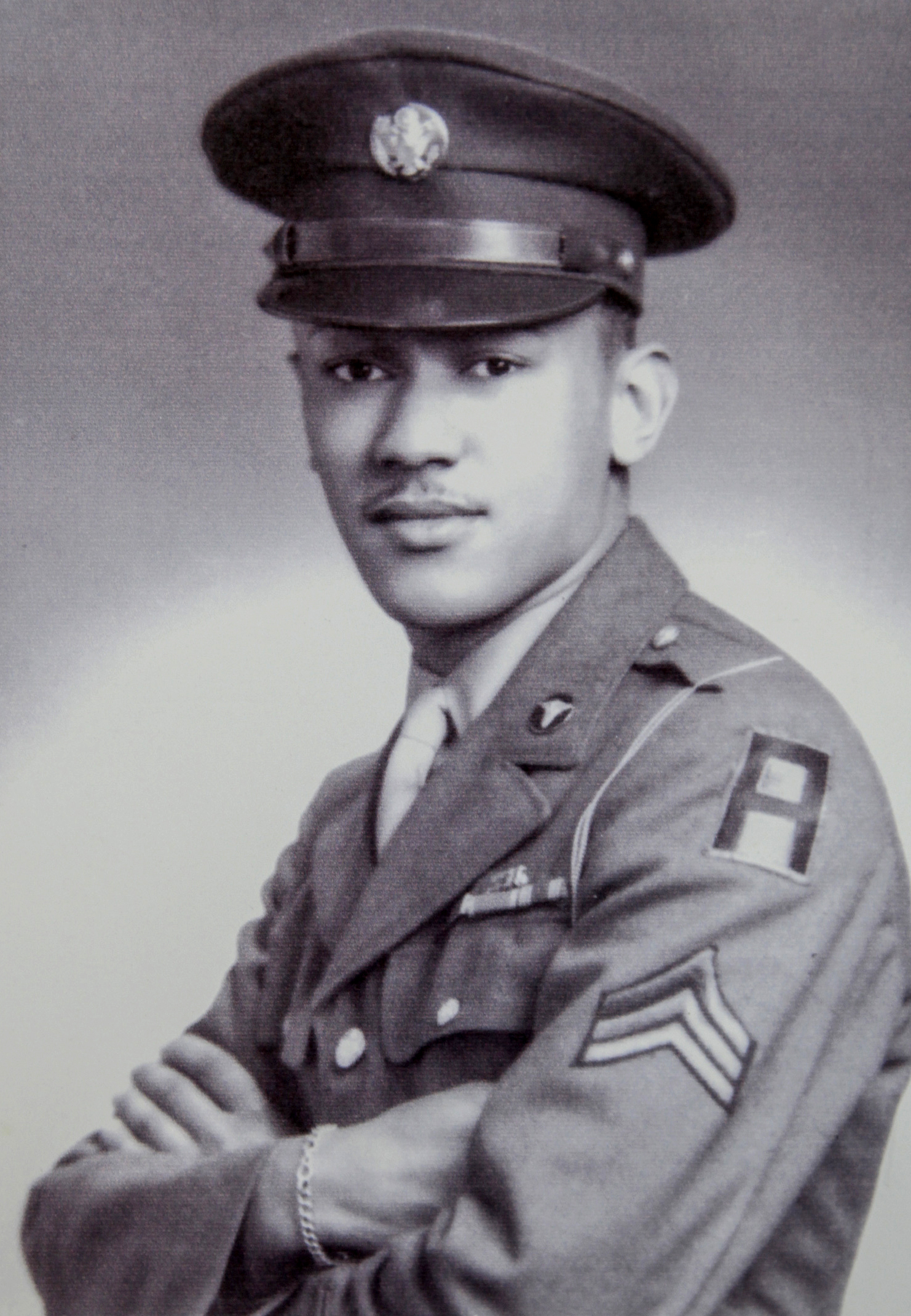

U.S. Army Cpl. Waverly Woodson was a medic at Omaha Beach in Normandy.

A group of lawmakers launched a new effort Tuesday to recognize a Black hero of D-Day with the Medal of Honor, enlisting the support of a Republican senator who agrees that the late U.S. Army Cpl. Waverly Woodson and his family have been denied the distinction because of the color of his skin.

On June 6, 1944, Woodson was a medic with the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion who went ashore at Omaha Beach in Normandy, France -- the most violently defended landing site in the largest invasion in history, which launched the successful Allied drive to defeat Nazi Germany. Despite being immediately wounded, he treated dozens, if not hundreds, of combat-wounded soldiers under the Wehrmacht's withering fire from the cliffs above the bloodied sands.

He later received the Purple Heart and Bronze Star Medal -- even though he had apparently been nominated for America's highest award for valor, the Medal of Honor, according to a military document unearthed by journalist and author Linda Hervieux for her book, "Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day's Black Heroes, at Home and At War."

Woodson displayed "really incredible heroism and selflessness despite being severely wounded," said Sen. Pat Toomey, a Pennsylvania Republican co-sponsoring the legislation with Sen. Chris Van Hollen, Democrat of Maryland.

At a press conference by Van Hollen, a longtime Woodson champion, Toomey described Woodson's actions, which were well documented and reported in 1944 news reports, as "absolutely staggering" efforts to save fellow soldiers of all races on Omaha Beach.

He said the bipartisan congressional effort will give President Donald Trump "the tool with which he can, with the stroke of a pen, correct this injustice and make sure that Cpl. Waverly Woodson gets the Medal of Honor he deserves."

Woodson grew up in Pennsylvania before enlisting and spent decades as a Maryland resident before his death in 2005.

Why Woodson was denied the recognition his family says he was due is not known, as few documents survive from World War II and many concerning Black troops' actions were lost, Hervieux's research found.

His wife, Joann Woodson, who participated in the virtual press conference with Van Hollen, Toomey and House lawmakers, said her late husband rarely spoke of his actions on D-Day or dwelled on the injustice of the valor award he did not receive. He was honored by the French Government on the 50th anniversary of the Allied invasion to liberate Europe. The couple, who met in 1952, walked the tranquil sands of Normandy together.

"He didn't say too much about it," she recalled on Tuesday. "He felt he was out there doing his duty, first of all, that [it] was his duty to his country."

His humility was on display in a rare interview by ABC News in 1994, in which he described being wounded even before he stepped off a landing craft -- but immediately began the work of aiding other troops around him felled by Nazi fire.

"There is no hero, it’s just that you’re there and you do what you can," Woodson told ABC News then. "There is no such thing as a color barrier, if I’m sitting here with material that you need as a white person. A bullet will kill you, it’ll blow your head off."

But he recognized that no matter how many lives he saved that day, the segregated military in 1944 saw him as a lesser man than the whites of the "Greatest Generation" who fought, sacrificed and fell in battle. No Black service member received the Medal of Honor in World War II until President Bill Clinton awarded it to seven men in 1997.

"They don’t give it to you. There were none given during the Second World War. For 30 years they never gave a Black man the Congressional Medal of Honor," Woodson said in the 1994 ABC News interview.

Hervieux said the soldier known as "Woody" was touted as a hero in an August 1944 press release, which "tells us he worked through his pain for 30 hours to treat hundreds of men and saved countless lives before he collapsed from his injuries."

"Waverly Woodson's actions, do they merit the Medal of Honor? Well I would argue that they do," said the author, who spent five years digging into the heroes erased from the pages of history and in D-Day films such as "The Longest Day" and "Saving Private Ryan."

While researching her 2015 book, Hervieux found a key document in the Harry S Truman Presidential Library that Woodson himself never knew existed during his lifetime.

"Here is a Negro from Philadelphia who has been recommended for a suitable award... This is a big enough award so that the President can give it personally, as he has in the case of some white boys,” stated the 1944 U.S. War Department memo to the Franklin D. Roosevelt White House.

It was written by War Department aide Philleo Nash to a colleague. The memo stated that Woodson’s commanding officer had recommended him for the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest U.S. valor award, but a U.S. general in Britain had upgraded the recommendation to the highest decoration.

It is the only document about Woodson known to have survived. Millions of Army personnel files and records were destroyed in a 1973 St. Louis warehouse fire.

Van Hollen, who has spearheaded efforts for the past five years to upgrade Woodson's Bronze Star, said the Army has insisted more documentation is necessary. Typically, a witness to such an act of selfless valor also is required for the Medal of Honor, but there are few survivors of the all-Black 320th, whose task was to launch balloons to thwart Nazi fighter planes from strafing Omaha Beach, where U.S. Army units suffered more than 2,500 casualties.

"We proceeded through the Army ... but we've obviously decided to take a different approach," Van Hollen said.

Noting the national reckoning on race over the past few months since Memorial Day, he added, "We believe this is the moment. We will be reaching out to the White House directly."

There are exceptions when it comes to eyewitnesses who can verify an individual extraordinary act of valor.

Two years ago, Trump presented a posthumous Medal of Honor to an Air Force airman killed in a 2002 battle in Afghanistan, Tech Sgt. John Chapman, even though the only eyewitnesses were U.S. Navy SEALs who believed he had been killed prior to his actions that merited the highest award. A drone video showed him fighting al-Qaeda fighters alone until he fell mortally wounded.

Woodson's widow, Joann, said she has been a dogged advocate for her husband's valor 76 years ago because it matters that Black heroes are recognized alongside their white comrades-in-arms during a war to defeat fascism and ethnic genocide.

"We want to have a legacy for our family," she said. "We have to keep history alive and history has to be as correct as much as it possibly can. And this is one way to get it corrected."