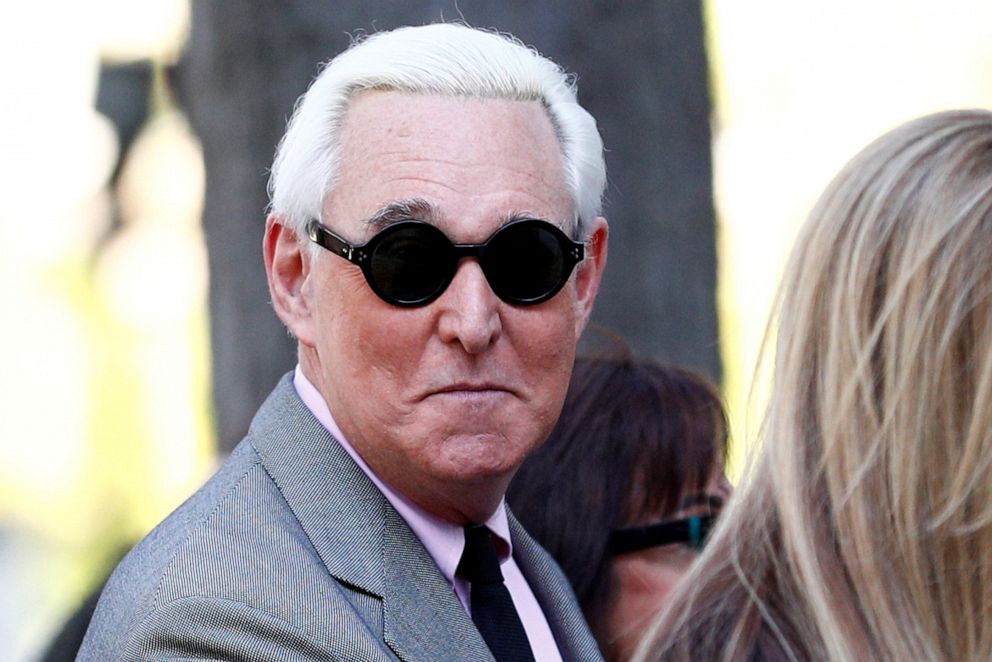

Roger Stone's trial brings back the Trump-Russia saga

Stone faces charges of lying to Congress and of witness tampering.

A federal prosecutor told jurors on Wednesday that longtime Republican operative Roger Stone lied to Congress, "because the truth looked bad for Donald Trump."

It was a pointed opening to the long-awaited criminal trial of the president's one-time personal political adviser.

"You might ask, why didn't Stone just tell the truth?" prosecutor Aaron Zelinsky asked jurors. "Roger Stone lied to the House Intelligence Committee because the truth looked bad for the Trump campaign, and the truth looked bad for Donald Trump."

The bulk of the charges Stone faces reflect allegations that he lied to Congress regarding his communications with associates about WikiLeaks. He also stands accused of witness tampering as part of an effort to keep humorist and radio show host Randy Credico from contradicting his testimony before the House Intelligence Committee in September 2017. If the jury finds Stone guilty on all counts, he could face up to 50 years in prison. He has pleaded not guilty.

The longtime GOP operative was excused from court early on Tuesday during jury selection complaining of "possible food poisoning." He arrived at the courtroom on Wednesday looking healthy and smiling, but when the jury was seated and opening arguments began, his grin gradually fell.

Zelinsky began investigating Stone's conduct while still part of former special counsel Robert Mueller's team, and stuck with the case after the Mueller report was published and the team disbanded. Zelinsky kicked off proceedings Wednesday by walking through the charges against Stone -- and included new details about Stone's interactions with the Trump campaign and Trump himself.

Stone spoke with Trump multiple times in the summer of 2016, Zelinsky said. It wasn't what was said on the calls that was significant, he told jurors -- the nature of their conversations is unknown. It was their timing. The calls coincided with key moments in Stone's interactions with people serving as Stone's back-channel conduits to WikiLeaks -- the organization that published thousands of stolen emails from Trump's Democratic political opponents.

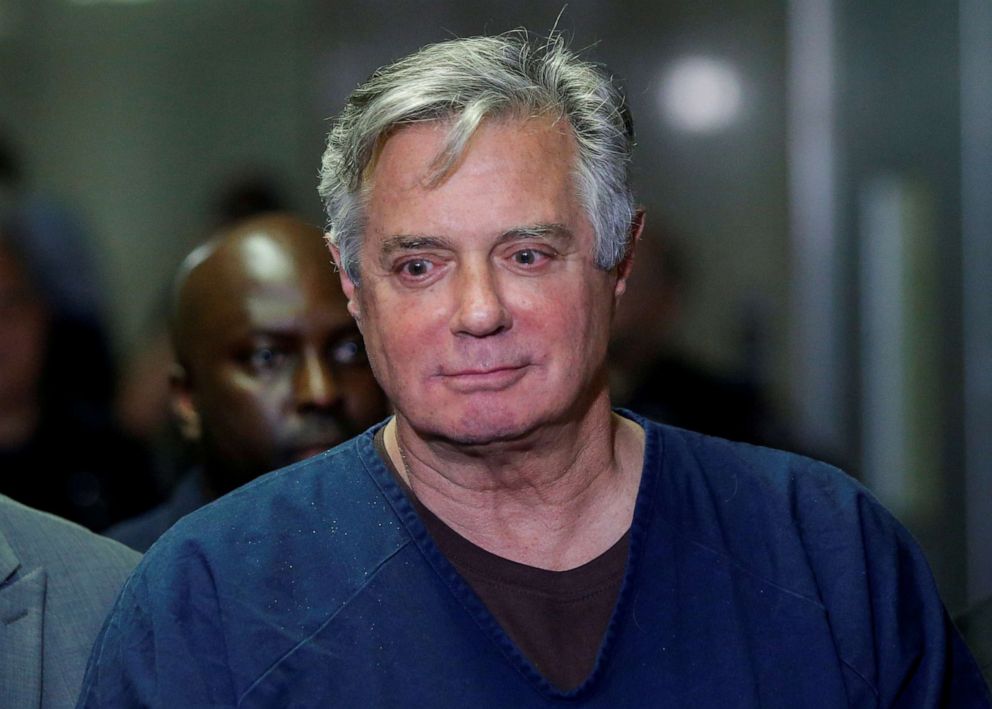

Zelinsky also described two notable exchanges Stone had with senior Trump campaign members. In a message to former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort, Stone said, "I have a plan to save Trump's (rear)," the prosecutor said.

Jurors heard about another email -- this one Stone sent to former Trump campaign CEO Steve Bannon.

"When Stone emailed Bannon, he said 'Trump could still win -- but time is running out,'" Zelinsky said. "But his way, in his own words, 'ain't pretty.'"

Zelinsky focused his remarks on the alleged lies Stone told to Congress -- each one represents a separate count against Stone. He told jurors why he believes Stone felt the need to lie, saying that the longtime Trump aide wanted to protect his political patron.

In response, Stone's counsel, Bruce Rogow, pointed out that his client had gone "voluntarily, without a subpoena," to meet with congressional investigators.

Stone's defense team told jurors that Stone complied with Congress and only omitted information he and his legal team viewed as being irrelevant to the "publicly stated parameters" of the committee's investigation.

"When you heard the government's opening statement, you didn't hear about Russia -- you heard about WikiLeaks and Julian Assange," Rogow said.

"You heard that Roger Stone spoke to the Trump campaign," he added, positing that there's nothing wrong with that -- Stone knew members of the Trump campaign personally.

Rogow argued that members of the committee deviated from the previously agreed upon, "publicly stated scope of the investigation," which he said was Russia, not WikiLeaks.

Prosecutors said they would seek testimony in court from Bannon, Rick Gates, who served as Trump's deputy campaign chairman, and Stone's onetime associate Randi Credico, who has been described by the prosecution as an "intermediary" between Stone and WikiLeaks.

Stone's defense team has questioned Credico's credibility, describing Stone's communications with Credico as "odious" and calling Credico "an impressionist."

Wednesday's court session also included testimony from Michelle Taylor, an FBI agent for 14 years who previously worked on the special counsel's investigation focused on Stone. She provided a window into the prosecutors' case. Taylor described a timeline of events over the summer of 2016, which over-layed the timing of actions by WikiLeaks and by the Russian hacking operation known as Guccifer 2.0, as well as Stone's communications with Trump, campaign officials and his intermediaries.

Taylor said she also reviewed public comments by Stone and by WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in the summer of 2016 -- in which they discussed plans to leak information about Hillary Clinton. Prosecutors played a clip of an Assange interview, during which he described those plans. Days later, the Democratic National Committee announced its server had been hacked.

Earlier this week, the federal judge overseeing Stone's case said she anticipated proceedings would last two weeks.

Editor’s Note: This story previously misidentified the statutory maximum for Roger Stone’s crimes as 20 years in prison. The actual maximum is 50 years in prison. We regret the error.