‘Spying’ -- what it is, what it isn’t and how espionage is evolving around the globe: ANALYSIS

Two retired, veteran U.S. federal investigators break it down.

When Attorney William General Barr told Congress that he believed that spying had taken place on President Donald Trump’s campaign, he sent the Senate hearing and the rest of the world into overload.

No description of scrutiny tends to prompt a stronger reaction than the connotation that something or someone was “spied” on, especially when the spying allegedly was conducted by our own FBI. The statement conjured images of spy novels of the worst kind, in which an American institution tries to usurp the government.

Testifying earlier this week before a congressional committee, FBI Director Christopher Wray refused to use the term "spying."

"Lots of people have different colloquial phrases," Wray said at the hearing, in a break with Barr. "I believe that the FBI is engaged in investigative activity and part of investigative activity includes surveillance activity of different shapes and sizes.”

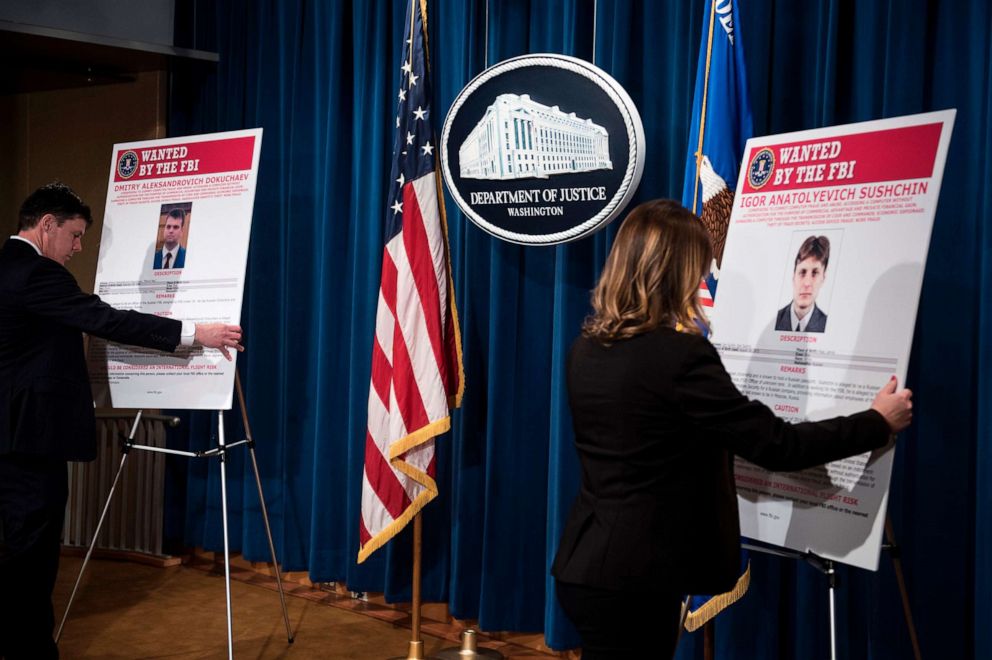

Nevertheless, the attorney general’s comments appear to have been prompted by a FBI counterintelligence investigation into Russian spying and espionage during the 2016 election which led the Justice Department to charge 12 Russian intelligence officers with stealing information on 500,000 voters -- and with hacking the Democratic Party computers during the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

This was in addition to the U.S. special counsel filing separate charges against 13 Russians and three Russian companies for their alleged involvement in a concerted campaign to influence the outcome of the 2016 election.

At the president’s Florida resort, Mar-a-Lago, a Chinese national recently gained legitimate access through social engineering and was ultimately arrested and charged for unlawfully entering a restricted zone and for lying to Secret Service agents. That individual had a trove of alleged electronic gear that many observers opined could be used for spying.

Then there are the multiple cyber “breaches” that have occurred over the last few years, including within the U.S. government, many resulting in millions of records being “stolen” by the alleged hackers, some of whom may be tied to foreign governments. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) lists 14 nations integrally involved with cyber incidents – either as the suspected offender or victim.

The U.S. is listed far more times as the victim while China, Russia, North Korea and Iran lead the world as suspected offenders.

As this globe-spanning spying continues -- and by some accounts seems to be escalating -- everyone everywhere seem to be targets. We shouldn’t be surprised that other nations are spying on us (it would be a shock if they weren’t), particularly when you factor in the level of political and corporate espionage.

It’s left many wondering what is going on and what might it all mean?

The history and evolution of espionage

Traditionally, the classic spy had a “handler” -- whom he or she got orders from or passed information to -- and the spy was classified as an “asset.”

Today with cyber spying, we see China using a specialized and highly-trained military unit to spy and the Russian’s possibly using beluga whales. It seems spying has become the tactic of choice against an adversary in 2019.

Spying, of course, dates back centuries -- with the Persians and Chinese among the first to develop prolific spycraft aimed at beating their adversaries. While over time, the means and methods of spying have changed, the goals have remained constant -- gather information and conduct espionage of an opponent -- which we now know the Russians did during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign.

So why do it? Why spy?

Different things motivate different people. Some spies are true government agents, doing it for the good of their own nation. Others can be non-governmental agents who are recruited, and spy for a payoff, as revenge or because of a personal belief or conviction.

While spying can occur in many forms, the intelligence can only be derived a few ways: signals intelligence (SIGINT), imagery intelligence (IMINT), measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT) or human intelligence (HUMINT). Most nation states perform all of these types of intelligence-gathering operations with the goal of obtaining insights into their opponents, and then using that information for an advantage.

While the first three types of intelligence-gathering are very technical, the last, human intelligence can require the most time and can contain the greatest chance of risk and reward.

Corporate espionage on the rise

In the corporate and industrial world, we’ve witnessed an explosion of espionage as well, all of it singularly focused on getting ahead of the competition. The problem is that nation states like Russia and China are also getting involved with corporate espionage and spying in order to strengthen their own economies.

The Huawei spying case, a consumer company accused by the U.S. of working for a foreign government has elevated concerns about cozy relationships between corporations and state actors.

We’ve seen numerous indictments from FBI-led investigations in which corporate espionage has been shown to have aggressively targeted the intellectual property of a foreign nation.

As the United States battles back against spying and espionage on all levels, one thing seems clear: nation states like Russia and China remain heavily engaged in these “spy games” and show no interest in stopping. This, despite their outward support of international issues like the Russian “help” in battling ISIS in Syria, and the Chinese purported willingness to “lean” on North Korea.

Clearly though, the modern -- and the most dangerous form of spying and espionage – unfolds in cyberspace. In the past, a spy might be able to steal the plans for a rocket or two. Today, with one click, a spy can snatch the whole arsenal. The cyber threat presents an ever more challenging environment as, increasingly, everything we do is tied to the cyber world.

The ‘internet of things’ and the future of cybersecurity

Today, many buildings are completely online -- with their elevators, HVAC systems and records all controlled by a computer a new reality known as “the internet of things,” or "IoT," an evolving system of interrelated digital devices. This makes the devices more user-friendly, but also increasingly vulnerable to attack and takeover.

The same thing is true for the U.S. government, which, back in 2008, reduced 4000 cyber access points to just 50 to make it harder for enemies to access the U.S. cyber systems.

To do so, the U.S. government spends more than anyone else on cyber security -- as of 2017 spending more than $28 billion.

While the Chinese and Russians have traditionally had the most aggressive foreign spying operations, numerous other nations also target the U.S.’s vital institutions and defenses, and America's corporations for information.

As our national intelligence network is fully immerses itself in trying to detect and defend against all types of espionage, one thing is certain: despite the available technologies, people will still be the best bulwark of defense in future counterintelligence wars.

Donald J. Mihalek is an ABC News contributor, retired senior Secret Service agent and regional field training instructor who also serves as the executive vice president of the Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association Foundation.

Richard Frankel is an ABC News contributor, retired FBI special agent who was the Special Agent in-Charge of the FBI’s Newark Division, and prior to that, Special Agent-in-Charge of the FBI’s New York Joint Terrorism Task Force. He is currently the Vice President of Investigation for T&M Protection Services.