Targeted by Mueller, what did Trump confidante Roger Stone actually do?

Former federal prosecutors say Stone could be in legal jeopardy.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller's investigators usually operate in secret, but an ongoing legal fight has forced them to admit publicly that they are examining Donald Trump's longtime confidante Roger Stone.

And while widespread discussion over Stone has often focused on what may have transpired in private, his very public statements and actions alone could put him in legal jeopardy, former federal prosecutors told ABC News.

Trump insists Mueller is on "a witch hunt," reciting the phrase "no collusion" at least 32 times in the past six months alone.

Mueller, however, has yet to offer a final assessment of alleged links between Trump's associates and Russian operatives. And just two weeks ago, FBI Director Chris Wray told lawmakers: "There is a very serious, ongoing criminal investigation" still underway.

Mueller's team is currently fighting – in open court – to compel a former Stone aide to testify before a federal grand jury about Stone and other matters. And last week, ABC News reported that Mueller's team is pressing for answers about Stone from their newest cooperator, former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort.

So what did Stone actually do – and could it even be criminal?

WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT STONE

Mueller recently charged 12 Russian spies for interfering in the 2016 presidential election by hacking into Democratic institutions and then orchestrating "the staged release" of stolen documents.

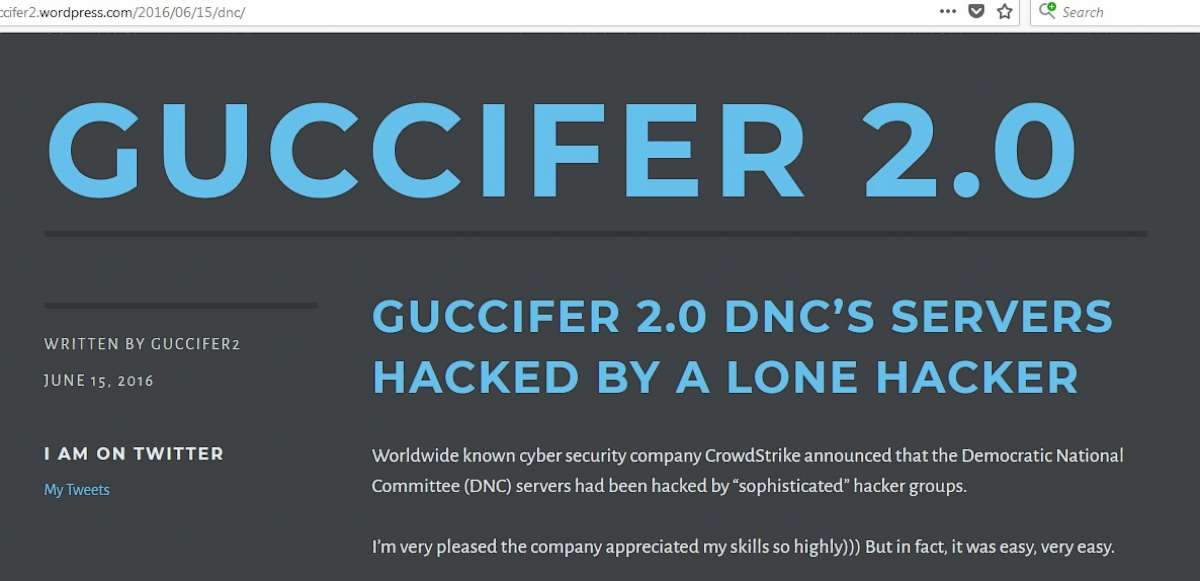

To help execute their "large-scale cyber operations," the Russian operatives created an online identity they named "Guccifer 2.0" and "falsely claimed to be a lone Romanian hacker," according to Mueller.

Their first big release came in July 2016, when Wikileaks published tens of thousands of emails heisted from the Democratic National Committee.

In the months right after the disclosure, Stone praised Guccifer 2.0 as the "hero" who "hacked and leaked" it all, but he also promised – at least a dozen times – that Wikileaks had yet to release its biggest blow against Hillary Clinton's campaign.

He repeatedly called the coming bombshell "an October surprise" because, he later explained to ABC News, an "intermediary" to Wikileaks founder Julian Assange told him early on, "It's coming in October."

Stone's teases offered tantalizing details – he repeatedly said the next release would come from inside the Clinton Foundation, and at one point in August 2016 he pronounced on Twitter that it would soon be "the Podesta's time in the barrel."

Stone has since insisted he was referring not only to Clinton's then-campaign manager John Podesta but also to Podesta's lobbyist brother, whose overseas business dealings were starting to receive media scrutiny.

Nevertheless, four days into October 2016, Guccifer 2.0 publicly claimed to have hacked the Clinton Foundation and posted several documents online. "Many of you have been waiting for this, some even asked me to do it," Guccifer 2.0 wrote.

And that same week, Wikileaks released thousands of emails stolen from John Podesta's personal email account.

There's no indication Stone ever discussed such disclosures with Guccifer 2.0, and he told ABC News it was a journalist's email that first suggested to him the Clinton Foundation had been hacked. But Stone has admitted exchanging "benign, innocent and even banal" private messages with the online persona.

In those exchanges, Stone expressed "delight" over Guccifer 2.0's Twitter account and, at Guccifer 2.0's request, offered minor feedback over a heisted Democratic document just posted online.

Mueller cited the exchanges in his indictment against the 12 Russian spies, describing Stone as someone who discussed "the release of stolen documents" with Guccifer 2.0, which Mueller said was created to "undermine the allegations of Russian responsibility" for the DNC hack.

Throughout the summer of 2016, Stone was engaged in his own effort to discredit those allegations, despite growing evidence from the U.S. intelligence community that Russia was to blame.

And Stone has consistently denied ever believing Guccifer 2.0 was a Russian front, even though media reports at the time insisted that was the case.

In August 2016, Stone published an article about Guccifer 2.0 headlined, "DNC Hack Solved, So Now Stop Blaming Russia."

In the article, Stone posted a link to Guccifer 2.0's website and encouraged the public to "have a look."

The website highlighted by Stone included batches of documents snatched from Democratic operatives and this statement from Guccifer 2.0: "I'm often asked if I'm afraid of being prosecuted by the FBI. My answer is No! I've expected it ... But it won't be that easy to catch me."

COULD STONE ACTUALLY BE PROSECUTED?

Stone's public statements and since-released private messages offer what former federal prosecutor Ed McAndrew called a "robust factual record."

And while there is no law explicitly outlawing the specific act of "collusion," Mueller is looking at a vast array of U.S. statutes that make certain acts of collaboration or assistance a federal crime.

Several former federal prosecutors suspected Mueller has been contemplating whether Stone should face conspiracy-related charges or even "aiding and abetting" or "accessory after the fact" charges.

Those former federal prosecutors were confident Mueller won't seek any indictment unless he has what former assistant U.S. attorney Joe Facciponti called "rock solid" proof.

"I suspect Mueller is looking to develop additional proof ... [and] more facts around Stone's knowledge and intent before bringing charges," said Facciponti, now with the firm Murphy & McGonigle in New York.

If Stone fully knew he was championing a hacker who – by Stone's own acknowledgment – stole and spread private material, "he's looking at 'aiding and abetting,'" according to McAndrew.

"They can show that he is encouraging [or] ... inducing them to engage in this activity. He's teasing it. He's the provocateur," McAndrew said.

If prosecutors conclude Stone was knowingly aiding the hackers, Stone could also be "exposed" to an "accessory after the fact" charge, as McAndrew sees it.

According to federal law, anybody who "comforts or assists" someone they know has committed a federal crime, and does so "to hinder or prevent" apprehension, "is an accessory after the fact."

The charge is rarely used in federal cases, especially by itself, "but it is there for – quite frankly – this type of fact pattern, where someone knows who the bad guys are, knows what they've done, and could be seen ... in any way assisting in avoiding exposure," McAndrew said.

Federal prosecutors have used the charge before in hacking-related cases, including when the global intelligence firm Stratfor suffered a major cyber-heist four years ago.

The Justice Department not only prosecuted the hacker who stole and then released millions of private records, the department also imprisoned Barrett Brown, a loose associate of the hacker, for being an "accessory after the fact."

Acting on behalf of a hacker he only knew as "o," Brown reached out to Stratfor to discuss whether "o" should redact information about certain individuals before releasing it.

Even though Brown didn't know "o's" true identity, prosecutors in Dallas concluded Brown was an "accessory after the fact" because – as a middleman – he created "confusion" over "o's" true identity and "diverted attention away from the hacker," according to documents filed with his plea deal in the case.

He was ultimately sentenced to a year in prison for the "accessory" charge and four more years for two other charges in the case.

Asked by ABC News to assess Stone's actions, a pro-Republican former federal prosecutor with links to Trump's administration said they "do come somewhat close to the line" of taking "affirmative steps" to help the hackers avoid prosecution.

But, speaking on the condition of anonymity so he could talk freely, he still questioned whether there is "sufficient" evidence to warrant an "accessory after the fact" charge, emphasizing, "It does require Stone to be more than a public advocate/cheerleader in support of the hacking."

The attorney who represented Brown four years ago, Ahmed Ghappour, was even more skeptical that Stone could face such charges, noting there's no evidence suggesting Stone's public statements "were at the behest of the Russians" or those specifically behind Guccifer 2.0.

While Stone's public statements and his "direct contact" with Guccifer 2.0 "give rise to legitimate suspicion, I have yet to see any real evidence of criminal wrongdoing," said Ghappour, now a professor at Boston University Law School.

An attorney representing Stone categorically denied his client has committed any crimes.

"Mr. Stone did not conspire, aid, abet, or act as an accessory with any computer hackers, Russian or otherwise," and unless they "work as a lawyer" in Mueller's office, anyone offering their opinion about Stone's potential culpability "is speculating without evidence," attorney Robert Buschel told ABC News.

Buschel has previously argued Stone's tweets and public statements were "nothing more than political speech" and "protected by the First Amendment."

Still, Stone recently told ABC News, "It's not outside the realm of possibility that [Mueller] may consider bringing some offense against me."

"A dedicated prosecutor could indict anybody for anything," he said.

WHAT WE DON’T KNOW

The former federal prosecutors who spoke with ABC News emphasized that Stone's fate could rest on what Mueller has gathered in secret.

"The real question is: What does the special counsel's office know beyond what's been made public," said McAndrew, now with the firm Ballard Spahr in Washington.

Mueller's investigators have already interviewed or contacted nearly a dozen associates of Stone, including his longtime aide Andrew Miller, who worked for him during the 2016 presidential campaign.

In June, Mueller's investigators sent a subpoena to Miller demanding he hand over any emails dated between June 2015 and June 2018 that mentioned six specific topics: Stone, Assange, Wikileaks, the DNC, Guccifer 2.0, or the other online Russian front DC Leaks.

Miller gave them a tranche of emails, but Mueller's team wants the former Stone aide to testify under oath to a federal grand jury, and Miller has resisted helping any further. The matter is currently before the U.S. appeals court in Washington.

Meanwhile, Mueller's investigators have access to all sorts of private correspondence from the time and to witness testimony behind closed doors. But perhaps "more importantly" they also have access to classified information secretly collected by the U.S. intelligence community and its allies around the world, McAndrew noted.

"That's the stream we really know next to nothing about," he said.

And such closely-held information is not always incriminating, Facciponti cautioned.

"The public record might just be the tip of the iceberg," but "further investigation might reveal that seemingly suspicious acts have entirely innocent explanations," he said.

Mueller's office declined to comment for this article.

ABC News' Ali Dukakis contributed to this report.