Tribal elders testify before federal officials on painful memories of Indian boarding schools

They shared their stories at Interior Sec. Deb Haaland's listening tour.

Native American tribal elders who attended Indian boarding schools as children shared their memories of physical and sexual abuse and emotional suffering with federal officials on Saturday, as the Biden administration confronts the U.S. government's role in a painful chapter of U.S. history.

"I still feel that pain," 84-year-old Donald Neconie said at the event, which took place at Riverside Indian School in Anadarko, Oklahoma, according to the Associated Press.

Neconie said that Riverside, which opened in 1871, has changed today but said, "I will never, ever forgive this school for what they did to me."

More than 500 American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children died over the course of 150 years in Indigenous boarding schools run by the American government and churches to force assimilation, according to a report released in May by the U.S. Interior Department.

Neconie, a former U.S. Marine and member of the Kiowa Tribe, recalled being beaten if he cried or spoke his native Kiowa language when he attended Riverside for more than a decade starting in the late 1940s.

"Every time I tried to talk Kiowa, they put lye in my mouth," he said, according to the AP. "It was 12 years of hell."

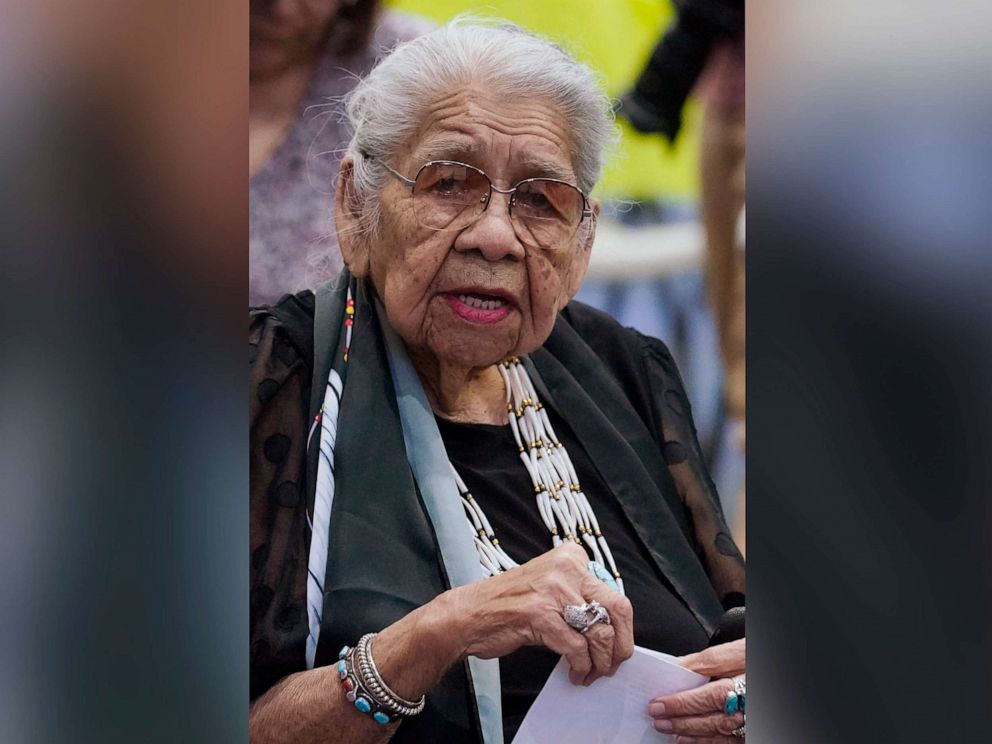

Brought Plenty, a member of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, said she was forced to cut her hair at a school in South Dakota and was forced to whip other girls with wet towels as punishment.

"What they did to us makes you feel so inferior," she said at the event, according to the AP. "You never get past this. You never forget it."

The event at Riverside kicked off Interior Sec. Deb Haaland's yearlong tour, "The Road to Healing," in which she will travel across the country to meet with families impacted by the painful legacy of Indigenous boarding schools and give them a platform to share their stories and heal from "intergenerational trauma," she said in May upon announcing the tour.

"It was a time to listen, to weep and to look ahead to healing our communities," Haaland wrote about the Riverside event in a series of tweets.

"This is one step, among many, that we will take to strengthen and rebuild the bonds within Native communities that federal Indian boarding school policies set out to break," Haaland said.

The tour is one of several actions that the Department of the Interior announced in May after releasing a report regarding the federal government's role in supporting the schools as part of an effort to dispossess Indigenous people of their land to expand the United States. Haaland testified before the Senate last month about the report's findings.

The Interior Dept. is also working to identify children who died and bring their remains back to their communities, as well as identify living survivors and descendants of attendees to document their experiences.

Haaland, the first Native American to hold a Cabinet position, oversees the government agency that historically played a major role in the forced relocation and oppression of Indigenous people.

She is a member of the Laguna Pueblo Tribe and previously told ABC News' "Nightline" that her great grandfather was taken to the United States Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, which was open from 1879 to 1918.

"When my maternal grandparents were only 8 years old, they were stolen from their parents, culture and communities, and forced to live in boarding schools until the age of 13," Haaland said at a press conference in May. "Many children like them never made it back to their homes."

Haaland commissioned the probe into the U.S. government's role in June 2021, which came after nearly 1,000 unmarked graves of Indigenous children were unearthed at Indigenous boarding schools in Canada.

Native Nations scholars estimate that almost 40,000 children have died at Indigenous boarding schools. And according to the federal report, the Interior Department "expects that continued investigation will reveal the approximate number of Indian children who died at Federal Indian boarding schools to be in the thousands or tens of thousands."