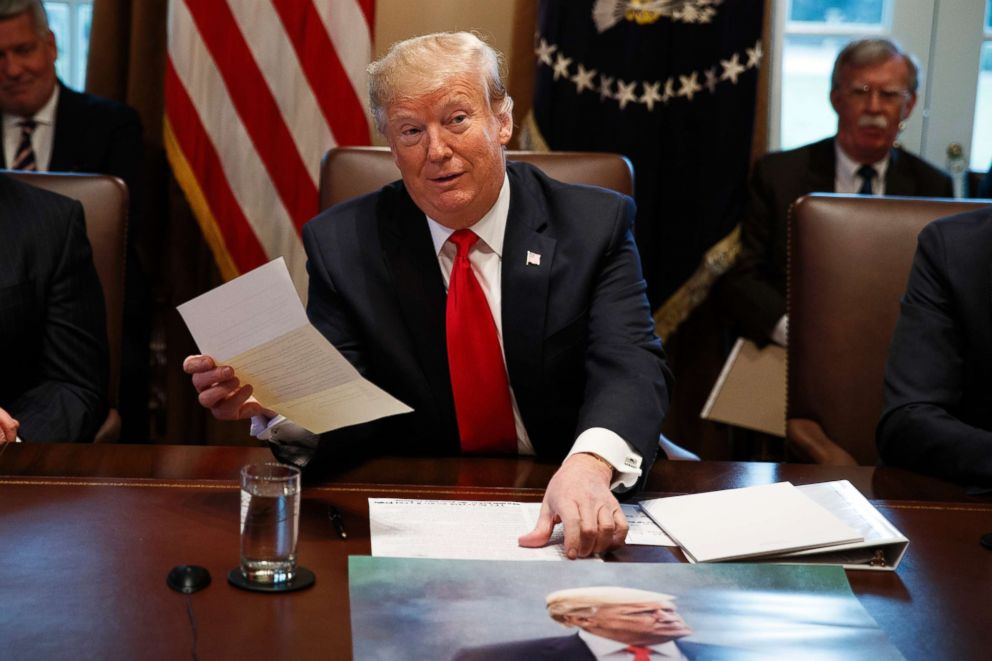

What could come out of Trump's 2nd summit with North Korea's Kim Jong Un

The two leaders have much to discuss at their forthcoming meeting.

Eight months after the summit in Singapore between President Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un of North Korea ended in a vague declaration about the "denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula," the U.S. hopes to put some meat on those bones this week as the two meet again, this time in Vietnam.

The Trump administration is pushing for concrete steps toward its goal of dismantling North Korea's nuclear weapons program. But the U.S. intelligence community and several top experts have warned that North Korea has no interest in giving up its nuclear weapons, which it sees as critical the Kim regime's survival, instead playing for time and sanctions relief.

Top U.S. officials said they're moving ahead with diplomacy to test that premise. But the initial steps that the administration has called for have been rejected by North Korean negotiators since June, and with an enormous gulf between the two sides, it's unclear how much can be accomplished in another sit-down -- a question complicated by Trump's own impulsiveness.

What the US wants

When Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and his North Korean counterparts had their first post-summit meeting last July, the U.S. sought a declaration of the regime's nuclear capabilities: a list of facilities, weapons, scientists, budgets and more. But the North Koreans refused, releasing a scathing statement afterward that accused Pompeo of "robber-like demands."

Since then, the U.S. seems to have abandoned a push for the whole pizza upfront and instead has settled on a slice-by-slice approach: a timeline of how the two sides can maintain each other's confidence and move toward their respective goals, meaning sanctions relief and security for North Korea and the Kim regime's elimination of nuclear weapons for the U.S.

That's where Special Representative Stephen Biegun's talks with his counterpart, Kim Hyok Chol, are focused now -- on "a roadmap of negotiations and declarations going forward," he said in a speech on Jan. 31. Biegun, Kim and their teams met for three days in Pyongyang at the start of February, and they've been negotiating a second agreement for Trump and Kim over the past week in Hanoi.

But Biegun's efforts have been undercut by Trump, who has eased some pressure on North Korea by saying he's in "no rush."

"I'm doubtful they'll actually get even a roadmap out of the North Koreans, given that the president wants to do the negotiating himself and the North Koreans are very likely to not give anything to the negotiators going in," said Michael Green, a former George W. Bush administration official and now Asia chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Even if the North Koreans do agree to a roadmap, it's unclear if it will be anything new or slivers of things previously offered.

Biegun said last month Kim has committed to "the dismantlement and destruction of North Korea's plutonium and uranium enrichment facilities" beyond Yongbyon, the well-known, sprawling facility where North Korea has produced material for nuclear bombs. But North Korea has never corroborated that.

Instead, Kim has dangled access for international inspectors to Yongbyon, but only if the U.S. takes "corresponding measures." Inspectors have visited Yongbyon twice before, with no success of shutting the facility down.

The other two sites likely to be offered are North Korea's nuclear test site Punggye-ri and a missile engine test site, known as Sohae. The regime said it has taken steps to dismantle both, but no outside observer has verified that, and neither site is particularly important to the nation's nuclear program anymore.

"The roadmap declaration is going to be in these three facilities ... because what the North Koreans are really good at is kind of reselling the stuff that they sold before," said Sue Mi Terry, a former CIA analyst and now senior fellow at CSIS.

But if they offer new access, including to the centrifuge facility at Yongbyon or previously undisclosed sites, that would be a promising step, several analysts said.

"A revelation of a few undeclared facilities is meaningful. ... Inspectors on the ground or electronic monitoring in place, perhaps with an IAEA relationship -- that would be meaningful," said Rebecca Hersman, director of the Project on Nuclear Issues at CSIS. "I start to think this is serious, even if I don't get a full declaration."

That seems unlikely to happen, however, and if it does, it will require the U.S. to pay some price.

What North Korea wants

The priority for North Korea is sanctions relief.

Although sanctions enforcement has relaxed since the first summit and China has resumed more normal ties, the country is still hurting from U.N. Security Council sanctions on everything from oil imports to seafood exports.

Pompeo said Sunday those sanctions will remain until there is "full, verified denuclearization." But he left an opening for some relief, telling CNN there are "lots of other ways that North Korea is sanctioned today that if we get a substantial step and move forward, we could certainly provide an outlet, which would demonstrate our commitment to the process as well."

North Korea also made clear in state media in December that its definition of that crucial term "denuclearization" means the removal of U.S. forces from South Korea and the surrounding area, the so-called nuclear umbrella the U.S. military provides to allies.

While Biegun said last month U.S. withdrawal has never been discussed, there are concerns Trump could agree to it, as he agreed in Singapore to unilaterally suspend U.S.-South Korean military exercises, taking the Pentagon and Seoul by surprise. Withdrawal would also be more in line with his instincts, as he's expressed opposition to U.S. bases overseas since at least the 1990s, accusing allies like South Korea and Japan of ripping America off.

The North also wants normalized relations with the U.S., but there are conflicting reports about the nation's interest in opening diplomatic facilities in each other's capitals -- so-called liaison offices. Sources briefed on the negotiations said North Korea is less interested in the idea, even though the administration has pushed it.

What Trump may want

What complicates the talks are Trump's own impulses, sometimes at odds with U.S. policy goals. In addition to his doubts about U.S. troops in South Korea, he could seek a positive headline like an end of war declaration amid his domestic political troubles.

The Korean War ended in an armistice in 1954. While an end-of-war declaration isn't going as far as a peace treaty, it would change the calculus on the peninsula, and it's something the president is seriously considering.

"President Trump is ready to end this war. It is over. It is done," Biegun said last month.

But several former officials warned that such a declaration could have disastrous effects long term. In particular, it would "make for good headlines, but ultimately have no impact in the nuclear program, and in many ways will be used by the Chinese, North Koreans and Russians to create mischief" and push for an end to the U.S.-South Korean military alliance, Green said.

North Korea would continue to posses 20 to 60 nuclear weapons, intercontinental ballistic missiles, short- and medium-range missiles that threaten U.S. allies, in addition to chemical and biological weapons.

"The situation on the ground has to reflect peace before you can declare it. You can't just politically declare peace while the situation has not changed. That is actually a dangerous situation," said Victor Cha, a top Korea expert in the Bush administration and one-time leading choice for Trump's ambassador to South Korea.

Even the promise that Trump holds out for Kim is not necessarily appealing to the young dictator. In a wild video Trump played for Kim and afterward showed the media, he promised a dazzling future of economic prosperity if Kim gave up his nuclear weapons.

But while Kim has taken steps to open up some markets and stated his intention to focus on economic development, he sits atop a communist system that relies on tight information control and would be undermined by the very things Trump is promising.

"It's a Confucian, communist, hereditary dynasty. ... Would Kim risk dynastic succession, his own regime's power?" Sue Mi Terry told former deputy CIA director Michael Morrell on his podcast "Intelligence Matters." "I really question, is he this kind of transformative leader? I don't see any indication of that."

Trump has strongly said otherwise: "North Korea, under the leadership of Kim Jong Un, will become a great Economic Powerhouse. He may surprise some but he won't surprise me, because I have gotten to know him & fully understand how capable he is," he tweeted on Feb. 8.

That sentiment, based on one day of meetings and a series of letters since, will be tested when they are together in person this week for only the second time.