Trump's COVID-19 treatment developed using cells originally drawn from fetal tissue

His antibody cocktail revives debate on scientific innovation and ethics.

The experimental antibody treatment taken by President Donald Trump to treat COVID-19, which he called a "cure," was developed using cells derived from human fetal tissue -- a research technique that his administration has sought in general to limit.

The disclosure has raised anew questions about the ethical use of fetal tissue and stem cells in groundbreaking research, ahead of a presidential election in which Trump has cast himself as a fierce anti-abortion candidate.

"President Trump has been an outspoken opponent of fetal tissue research -- and he used it. I just think it's incredibly hypocritical across the board," said Lawrence Goldstein, member of the National Institutes of Health's Human Fetal Tissue Research Ethics Advisory Board and senior faculty member at the University of California at San Diego.

The Regeneron cocktail was developed using mouse and hamster cells. But the effectiveness of the antibody's ability to neutralize the virus was tested using a cell line derived from an aborted fetus in the 1970s.

Regeneron said it does not consider the treatment to have relied on fetal tissue, since the cells were acquired so long ago. The 293T line used continued to divide and grow within a culture for decades, and for use in scientific discovery, even though they originated from fetal tissue, according to experts.

They "are considered 'immortalized' cells (not stem cells) and are a common and widespread tool in research labs," a Regeneron spokesperson told ABC in a statement. The cell line "wasn't used in any other way, and fetal tissue was not used in this research."

Other companies racing to find effective treatments, and at last, a vaccine against the novel coronavirus, have also made use of these cell lines, which are commonly used in medical research.

A spokesperson from AstraZeneca, one of the companies currently developing a vaccine, confirmed to ABC News their use of the 293T cell line in their vaccine development, further emphasizing, it is "derived from one of the most common cell lines used in biological research."

The New York Times reported that Moderna is also relying on the same cell line. When reached for comment, a Moderna spokeswoman told ABC News that it has "used this in the past for laboratory research for the vaccine, but we do not use this for making the vaccine."

In 2019, the administration suspended federal funding for scientific research reliant on fetal tissue cells derived from an elective abortion. Fetal tissue from miscarriages are permitted under this statute, although many scientists say it's difficult to use because there are often abnormalities and other issues.

But the policy allowed older existing cell lines derived from aborted fetal tissue -- such as the one used by Regeneron -- to be used.

"Promoting the dignity of human life from conception to natural death is one of the very top priorities of President Trump's administration," the Department of Health and Human Services said in a statement at the time. "Intramural research that requires new acquisition of fetal tissue from elective abortions will not be conducted."

When asked to comment, the White House and a senior Health and Human Services official would only note that Regeneron's research complied with its 2019 policy, which allowed previously established cell lines.

"The Administration's policy on the use of human fetal tissue from elective abortions in research specifically excluded "already-established (as of June 5, 2019) human fetal cell lines," the HHS official said in a statement. "Thus, a product made using extant cell lines that existed before June 5, 2019 would not implicate the Administration's policy on the use of human fetal tissue from elective abortions."

The Charlotte Lozier Institute, which opposes abortion rights and fetal tissue research, called the debate on Trump's treatment "uninformed" and expressed support for the development of the antibody cocktail.

"The cells were not used to create the antibiotic cocktail itself," David Prentice, vice president and research director, said on a Friday press call. Prentice also sits on the NIH fetal tissue ethics advisory board, and told reporters those studies were "separate from production" of the cocktail treating the president.

"Yes, the drug is still tainted by the stem cell or aborted fetal tissue line, cell line," he said. "But it's just not tainted in any of the ways that people claim that it is, and certainly not in a way that makes Republicans inconsistent."

As of yet, there is no known "cure" for the novel coronavirus. Some treatments have been given emergency authorization. The antibody cocktail given to the president -- made by biotech company Regeneron -- is thought to be promising, though still in its experimental phase.

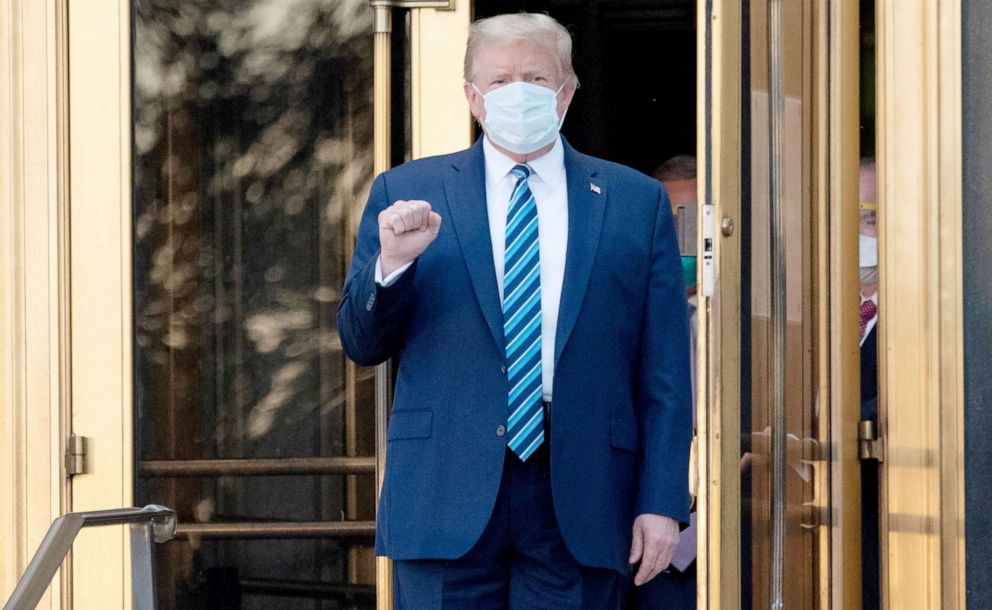

"To me it wasn't therapeutic, it just made me better," Trump said from in front of the Oval Office Wednesday. "I call that a cure."

Scientists say countless important medical discoveries have relied on similar lab-grown cells that were originally derived from stem cells, special "blank-slate" cells usually taken from human embryos or fetal tissue.

"Research using human fetal tissue has been essential for scientific and medical advances that have saved millions of lives, and it remains a crucial resource for biomedical research," the International Society for Stem Cell Research wrote in a July letter to the new fetal tissue ethics board established by the Trump administration.

"Fetal tissue has unique and valuable properties that often cannot be replaced by other cell types," the group wrote.

In August, the HHS ethics board advised rejecting funding for nearly every proposal involving fetal tissue: 13 out of 14. The one approved proposal relied on tissue already acquired, "with no need to acquire additional tissue," according to the board's report; it is also noted that "tissue from miscarriage was a viable alternative to HFT."

Deepak Srivastava, president of the Gladstone Institutes and immediate past president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research, said it's important to note that if the Trump administration's ban was in place when the cell line Regeneron uses was made -- the innovations that have come from it would not have been possible -- including testing the treatment Trump received.

"That would not be available to make the drugs that we've had -- and Trump would not have received those antibodies," Srivastava said. "And I am worried about any moves that would slow further discovery -- because we're still in the middle of this pandemic."

ABC News' Eric Strauss and Sony Salzman contributed to this report.